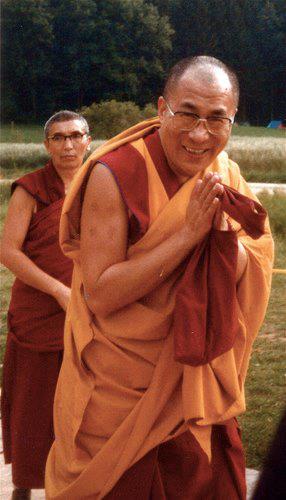

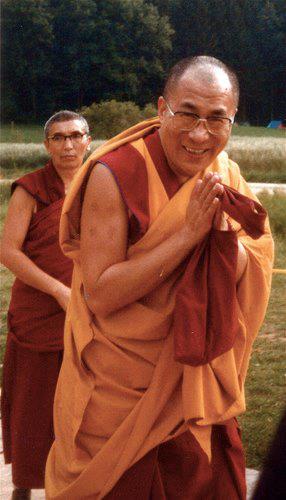

His Holiness the Dalai Lama: The practice of Dharma is that which enables us to be true, faithful, honest and humble, to help and respect others, to forget oneself for others.

1 – The Thirty-Seven Practices of the Bodhisattva

His Holiness the Dalai Lama: The practice of Dharma is that which enables us to be true, faithful, honest and humble, to help and respect others, to forget oneself for others.

I want to give a few explanations concerning Dharma, and more particularly, Mahayana Dharma, and the necessary preparations for the initiation. I shall be brief, but I hope to give you a fruitful teaching that you will like. You are not tired, and neither am I. So we are all of us in excellent condition for hearing about the Dharma.

There are many rules in the vinaya (rules for monastics) concerning the physical manner in which the Dharma should be listened to; one should be seated in the right posture, be bareheaded before the guru, the monks should have their right shoulder bare, and so on. But all these rules are waived when people are ill. We are not ill, but this very hot sun may bother you and make you fall ill. So for the time being let us abolish all those rules, and let those with umbrellas open them, the monks cover their heads with a fold of their robe, or a white handkerchief – something white is excellent protection against the hot sun. There are great gurus who have the power to change the elements, but I don’t have this power, so I would ask you to take care of yourselves.

We shall start by reciting the Heart Sutra of the Prajnaparamita, followed by a short prayer to Manjushri, the great mandala for our request for teaching. Then we shall take short refuges at the end of which we shall change one sentence: instead of saying “may we, by the practice of the paramitas, etc, reach buddhahood as rapidly as possible for the good of all sentient beings” you would say “may we by listening to this teaching,” while I shall say “may I by giving this teaching.” After that you will say the opening phrases of the bodhicitta prayer. Our motivation, which I will talk to you about in detail later, must be strong at this time, it will therefore be, it is, to reach buddhahood for the good of all beings and to give all our merit for that. At the end you will clap your hands three times—this is a reminder to purify our minds and to get rid of interferences. Do not clap more than three times, it is not like the end of an entertainment or as though you were applauding a famous speaker!

You have come a long way to be here, from various countries, and often with much difficulty and trouble. There are the strikes, and there are many of you, and it is not easy to get here. And you have not come here with the intention of going to a festival, for entertainment, or to do a good business deal, or for any personal glory. You have come here to hear the Dharma, more precisely Mahayana Dharma, to receive a tantric initiation, more particularly that of anuttarayoga, and among these Kalachakra. To some completely samsaric people, this may seem strange and even comical. Never mind… Even if we have not come with a perfect motivation, this is already something very great, the goal is an excellent one.

Whoever we are, of a white, yellow or dark race, whatever our social position, and also all the animals, down to the smallest insect, we all have the feeling that we are a “me”. Even if we don’t understand the nature of the “me,” we all know what this me wants: to avoid suffering and obtain happiness. There are extremely varied degrees of suffering, ranging from the smallest worry to certain intolerable and lasting kinds of pain. There are countless kinds, but whatever they are, we try to protect ourselves from them. Animals do the same, in this way they are exactly like us. Only they have no method for doing this. They don’t make plans in advance or look ahead. They try their best to avoid the suffering of the moment and to take the pleasure of the moment. They don’t go beyond this. Therefore, though the basis of our motivation, to avoid suffering and obtain happiness, is exactly the same, our means of avoiding or obtaining it are, in our human case, multiple. Degrees of suffering are infinite, from a mere headache to torture, to mention only physical pain, while the happiness we wish to obtain have just as many appearances. But their basis is the same: happiness, suffering, only the means vary. Then we aggrandize what we call “me.” We want happiness for “my” family, “my” friends, “my” country.

What we call happiness and suffering take on deeper, wider meanings. After simple satisfaction of the most immediate necessities, the notion of “happiness” grows complex, the means of obtaining it multiply and also the levels at which we situate happiness rise. The creation of language, writing, the various educational and social systems, trade skills, factories, medical progress, the creation of schools, hospitals, all derive from this simple and single basis: obtaining happiness, avoiding suffering. The whole life of the world is completely engaged in this single quest. Philosophies try to resolve the issues raised by this quest, why our nature is what it is, what the structure of the world is, etc. They seek the real cause for this happiness and suffering, and seek an explanation and solution of principle. They do this by the most varied of paths, and proceed whether their reasoning is right or wrong. It is also in response to this search that certain philosophies have been made systematic at the social and political level.

Communism, for example, holds that achieving happiness and eliminating suffering will come from an egalitarian system, where the “preponderance of one social class,” a majority exploiting the minority, will cease to exist. Religions, too, want to solve this eternal problem, using various approaches, and by explaining its causes. One can divide into “doctrinal” those who seek an answer in general and causal principles, and “nondoctrinal” those who seek a practical solution on the material level. In this sense the teaching of the Buddha is doctrinal.

We find that the suffering of the body often comes from the mind, or that where physical pain is equal, a calm and happy mind will suffer much less than an agitated and unquiet one. We also find that many people who have great wealth, an abundance of everything material wellbeing can bring, are depressed, anxious and unhappy, while others whose practical life is full of difficulties have a happy mind, feel at peace within themselves and give the impression of great serenity. Someone whose mind is balanced, open, lucid, who foresees the attitude he will have in case of difficulties, will remain at peace, even if he has very serious troubles and will know how to face them and overcome them. Whereas an agitated and unquiet mind, limited and unreflective, will be completely at a loss when faced with the slightest unforeseen incident. All this shows that the mind is much more important than the body. Therefore if the state of our mind enables us to bear and even to feel either much more or much less our physical suffering, we should attach great importance to our way of thinking. The “preparation” of our mind is therefore extremely important, and to practice the Buddha’s teaching, the Dharma, is our excellent preparation.

Take our example, that of the Tibetan people. I notice, and many people have told me too, that in spite of the troubles and difficulties of their situation, Tibetans on the whole—of course there are exceptions—remain smiling, even-tempered and good-humored, and pleasant towards each other. Their behavior is usually very correct. In the past few days I’ve had many audiences with Tibetans from many places, Nepal, Bhutan, Sikkim. They have confirmed this impression. It is quite certain that this attitude is a “fruit” of the Dharma. Not all of them understand the Dharma properly, some practice it only a little or not correctly. But it has for so long impregnated our country, governed our way of life and thinking that, despite their little knowledge, people have experienced its influence, and a good number have practiced, and practiced it fully.

But if this happy attitude of the Tibetans which helps them to bear the losses they have suffered—family, wealth, country—is a consequence of the merits accumulated through the practice of Dharma, one can also consider that our present difficulties derive too from a lack of merit. This situation of Tibet is not hopeless. I am profoundly convinced that, everything in samsara is subject to swings of the pendulum, ups and downs. Now we are at the lowest point of the curve, I am convinced it will turn up again. Let us help it to do so by practicing the Dharma, by accumulating a considerable amount of merit.

Let us practice the Dharma. Let us forget for the time being karma and the next life, let us consider the fruits of existence in this life only. The fruits it yields will be harvested by our mind and above all by others. By means of a noble, pure and generous mind we will spread joy around us, we shall feel a great peace and communicate it to others.

Look around us at this world we call “civilized” with its 2,000 years of civilization. This world has tried to achieve happiness and prevent suffering, but it has tried to do so by false means. By deception, corruption, hatred, by exploiting others, by abusing power over others. It has sought only individual and material happiness. By setting individuals against each other, it has brought a time of fear, hatred, suffering, murder, and famine. If in India, Africa and other countries, poverty and famine can hold sway, it is not because natural resources are lacking, and it is not because the “means” to bring about lasting wellbeing are lacking. Never has medical science been so advanced, never have there been so many comforts and amenities, never have communications been so easy. But everyone has looked for his own profit, without fear of oppressing others for this selfish aim, and this sad and pitiful world of war, fear and corruption is the result. The situation of Tibet is also related to this state of the world. The root of this civilization is rotten, and the world is suffering, and if it continues in the same way it will suffer more and more.