His Holiness the XIV Dalai Lama: All phenomena are devoid of an intrinsic nature; all phenomena are thoroughly pure from the very beginning; all phenomena are thoroughly radiant; all phenomena are naturally transcendent nirvana and all phenomena are manifestly enlightened.

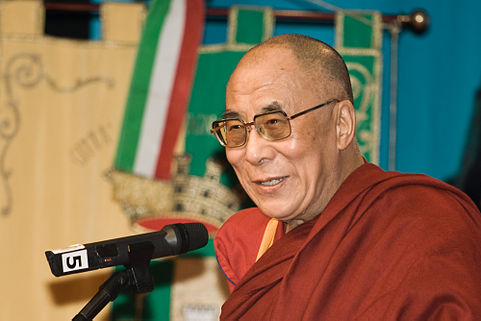

Commentary on the Rosary of Views by His Holiness the XIV Dalai Lama

19-21, 2004, Miami, Florida. Translated by Thubten Jinpa. Sept. Transcribed, annotated and edited by Phillip Lecso.

Day Three

His Holiness the XIV Dalai Lama

To pick up from where I left off yesterday, but first I would like to share that it is important to bear in mind and understand that one commonality of all of the teachings of the great religious traditions of the world is that the emphasis is not so much relying upon external material conditions for one’s wellbeing and happiness but rather to focus upon internal development of one’s inner resources.

From a philosophical point of view as I discussed yesterday, the difference or demarcation between the Buddhist and non-Buddhist traditions is whether or not one subscribes to a belief in some sort of eternal, permanent self. In Buddhism one of the primary grounds upon which the notion of an eternal, permanent and unchanging self is rejected is because of its emphasis on the understanding of the law of cause and effect, causality or dependent origination. The essence of the Buddha’s teachings can be summarized into two elements. First is its philosophical standpoint, which is the view of dependent origination and the conduct or action of the Buddha’s teaching, which is the action of no-harm and compassion.

Because of the basic Buddhist understanding of dependent origination as its fundamental philosophical standpoint, there is a deep emphasis placed upon the understanding of the law of cause and effect. The point made here is that if on the causal stage one creates the causes and conditions which have the potential of bringing about suffering and harm then as a consequence of creating those causes and conditions at the stage of the effect or result, one will experience consequence or effects consonant with the set of conditions that one created. Similarly on the causal stage, if one engages in actions that are constructive with the potential of benefit and help, then these actions on the resultant stage will bring about consequences and effects which are again consonant with that set of conditions. The point being made here is that a beneficial action will lead to a beneficial result and negative actions or negative causes and conditions will lead to undesirable consequences and effects. In essence the heart of the teachings on dependent origination is basically this: if one does good, one will reap beneficial results and if one does evil, one will reap undesirable consequences. Since harm causes harm and violence or suffering and pain therefore there is the emphasis in the Buddhist teachings on avoiding harm and violence.

When one speaks of avoiding harm or avoiding engaging in violent activity, how does one demarcate between violence and nonviolence, harm and non-harm? This distinction cannot be made simply on the basis of the external appearance of the act itself. The demarcation must be made on the basis of the motivation, the state of mind that underlies the act. At the root of this issue is compassion as one’s motivation and because of this, nonviolence must be defined in terms of an action grounded in compassion. Therefore the Buddha’s teaching is often characterized as being rooted in compassion.

So when one speaks of engaging in acts that are non-harmful and which avoid violent activity, one can understand this on two levels. On the initial level, when one speaks of engaging in actions that are not harmful motivated by compassion and a concern for other sentient beings, one deliberately refrains from engaging in harmful actions. This is the first stage of nonviolence or non-harm where it is primarily in the form of refraining from certain actions. However as one’s capacity for compassionate activity increases then on the second level when one is more advanced, not only does one deliberately refrain from harming others but one must actively engage in actions that are beneficial and helpful to others.

This practice of compassionate action is the skilful means or method aspect of the spiritual path and the understanding of dependent origination is the wisdom or insight aspect of the path. When one can combine these two together within one’s own spiritual practice then one’s practice and actions will become truly powerful.

When one speaks of the Buddhist understanding of dependent origination there are of course different levels of understanding. One level of understanding of dependent origination is in terms of cause and effect, how every thing and every event comes into being through depending upon causes and conditions as well as other factors. This is one level of understanding. Also in the writings of the Madhyamika or Middle Way, there is a deeper understanding of the meaning of dependent origination. Here not only are things and events understood to arise in dependence upon causes and conditions but also their very identity as things or events are dependent upon other factors. Therefore they are dependent upon conventions, designations and so on.

This idea of dependent origination, although in terms of a systematic presentation may have primarily originated in the Buddha’s teachings, as far as the philosophical perspective of dependent origination is concerned, this has relevance in many areas such understanding our environment or understanding the global economy, even politics. This idea of dependent origination is applicable and useful in many areas of human activities because the more one is able to appreciate the deep interconnectedness of all things and every event. One will then naturally have a much more holistic perspective on everything.

If one were to ask: “What is the essence of the Buddha’s teaching? What is the heart of the Buddha’s teaching?” One could respond by saying that the essence of the Buddha’s teaching is the efficacy of a way of conduct rooted in compassion and that is not harmful or nonviolent which is based upon the philosophical standpoint of dependent origination. This truly captures the essence of the Buddha’s teaching.

In terms of the goal of spiritual practice in Buddhism, one can speak of two goals. One is the temporary goal of attaining rebirth in the higher realms endowed with the facilities for engaging in the practice of the Dharma and the ultimate goal is the attainment of liberation from cyclic existence. Rebirth in a higher realm is characterized as a temporary goal as it is in the higher realms that one has a relative degree of freedom from many of the more evident forms of pain and suffering. This accords the individual the opportunity to engage in spiritual practices and so on. As for the ultimate goal of the attainment of liberation, liberation here is understood as the total freedom from suffering characterized by the complete elimination of fundamental ignorance which lies at the root of one’s unenlightened existence. It is this type of liberation that is the ultimate goal or object of aspiration for a Buddhist practitioner.

The Buddhist texts speak of four factors of human aspiration and these four factors are listed as the attainment of one’s mundane objects of aspiration, the acquisition of wealth, the practice of Dharma and the attainment of nirvana. Wealth is seen as a factor that would enable the individual to attain their mundane aspirations so that the individual has the facilities to then engage in the practice of the Dharma. The practice of the Dharma is the factor that leads the individual to attain liberation and Dharma here refers to the practice of the three higher trainings: training in morality, meditation and wisdom.

Generally speaking, with respect to the first two factors, the attainment of mundane aspirations and the means through which that attainment is achieved is material wealth. Generally speaking in North America, you have in most cases achieved this. Because of this many Tibetans are eager to come to the United States because they believe that by coming here they will at least be able to fulfill the first two aspirations. These Tibetans are not content with the three higher trainings and because of this they want to run to the United States.

However in the case of many individuals in North America, there are individuals who, after having gained a relative degree of wealth and the fulfillment of their mundane aspirations, feel a sense of incompleteness and a sense of disillusionment and frustration. Such a sense of incompleteness or frustration with material success is understandable because if one thinks more deeply one will recognize the importance of having some sense of contentment with relation to material facilities and acquisition. Material acquisition, wealth and so on, which are finite, which are limited, which can cease to exist, any object that has an end, that is finite, are in the end unreliable. With relation to such objects it is always wiser to have a sense of contentment instead of being never satiated.

However in relation to phenomena that have the potential of being infinite such as the positive qualities of the mind and so on, with relation to these, one should not have a sense of contentment; one should always aspire for more. Most of us however do the opposite with relation to material acquisitions and so on, all of which are finite and have limits. We tend to have very little contentment in regard to these, and in relation to the spiritual or mental qualities, we have an easy sense of contentment. Also this inability, to be content with what one already has, is very deeply related to the huge gulf between rich and poor especially in the more affluent societies.

Since in the Buddhist text the attainment of mundane aspirations is understood to be a legitimate goal of spiritual activity, also not only is the attainment of rebirth in a higher realm in a future life an object of aspiration, having one’s aspirations fulfilled in this life as well is something one should aspire for.

With relation to the ultimate goal of a Buddhist practitioner, which is the attainment of liberation referred to as the definite goodness, there is the liberation from cyclic existence and also the attainment of full Buddhahood. In the Mahayana texts there is the identification of two ultimate spiritual goals: one is the attainment of liberation from cyclic existence and the other is full enlightenment. Corresponding to these two ultimate goals of spiritual practitioners there are two main obstacles that one must overcome. The obstacle to the attainment of liberation [from cyclic existence] is the defilements in the form of afflictions or kleshas and the obstacle to the attainment of omniscience or full enlightenment are the subtle obstructions to knowledge.

How does one distinguish between the defilements in the form of afflictions and the defilements in the form of subtle obstructions to knowledge? Here, of course depending upon the philosophical understanding on the ultimate nature of reality, there are differences amongst the [various] schools [of Buddhism]. The most definitive and profound explanations of these are found in the works of Candrakirti, Buddhapalita and Santideva. In their writings there is a very explicit explanation of the primary form of the afflictions being that of one’s natural grasping at the true existence or the substantial existence of all things and events. This grasping at true existence in all phenomena is understood as a form of mental affliction. In fact this is also understood to be the fundamental ignorance that underlies one’s unenlightened existence; it is this innate grasping at true existence or substantial reality of all phenomena.

This is also very clear in Nagarjuna’s own writings. For example in the Seventy Stanzas on the Middle Way, Nagarjuna explicitly states that when identifying the twelve links in the chain of dependent origination, the first link, which is ignorance, is explained in terms of grasping at substantial reality and the true existence of the self and of phenomena. He then states that this ignorance, this grasping at true existence of the self and all phenomena, sets in motion the entire chain of the twelve links, giving rise to volition actions and so on. This culminates in birth and death. So here there is an explicit recognition that the grasping at true existence and substantial reality is the basic form of affliction and is the fundamental ignorance.

Verse 62: Through understanding the truth, ignorance, which arises from the

four perverted views, does not exist. When this is no more, the

karma-formations do not arise. The remaining [ten members vanish] likewise.

Verse 64: To imagine that things born through causes and conditions are real

the Teacher calls ignorance. From that the twelve members arise.

Similarly in Aryadeva’s Four Hundred Stanzas on Emptiness, he compares the grasping at true existence to the basic body faculty and all of the other derivative afflictions are like the other sense faculties. So just as all of the other sense faculties such as vision, hearing and so forth are all based upon the basic body faculty, in the same manner, all of the derivative afflictions such as desire, anger and so on are grounded upon the grasping at the true existence of things. Aryadeva explicitly draws a causal connection between the derivative afflictions with grasping at true existence.

Verse 135: As the tactile sense [pervades] the body

Confusion is present in them (the disturbing emotions) all.

By overcoming confusion, one will also

Overcome all disturbing emotions.

Having identified what this fundamental ignorance is, Aryadeva then goes on to state that it is through cultivating insight into the suchness of dependent origination, the ultimate nature of dependent origination, one will then dispel this delusion. Here by developing insight into dependent origination which is emptiness is the key antidote for dispelling ignorance, Aryadeva is implicitly recognizing as well the grasping at true existence of self and phenomena to be a form of mental affliction.

Verse 136: When dependent arising is seen

Confusion will not occur.

Thus every effort has been made here

To explain precisely this subject.

Therefore one can find very explicit explanations of the defilements in these texts. Another question arises: “If this fundamental grasping at the substantial reality of the self and phenomena is a form of mental affliction, what then is the subtle obstruction to knowledge?” Here Candrakirti states in his own commentary The Supplement to the Middle Way or Madhyamakavatara that it is the imprints implanted within one’s mind by those grosser afflictions, by the grasping at the true existence. They are the imprints and propensities for grasping including the dualistic perception that one has [of self and other] as well as the perception of the duality of the Two Truths, conventional and ultimate truth. These are the subtle obstructions to knowledge.

Chap. 11: The tenth strength of the Buddha is to know unhindered, unconfined,

Verse 40 That by the power of his omniscience,

The defilements and their tendencies are instantly removed

And that his followers arrest defilements through their wisdom.

This perspective or way of distinguishing between the two defilements is quite different from the perspective of another viewpoint where the grasping at the selfhood of phenomena and the grasping at the self-existence of the person are felt to be different.

For the path to the attainment of such an ultimate goal which is the full enlightenment of Buddhahood there are two vehicles explained in the scriptures. One is the Perfection Vehicle of Sutra and the other is the Vajrayana or Indestructible Vehicle. Within the Vajrayana, as discussed yesterday, there are three divisions identified in this text. These are the Kriya Tantra or Action Tantra, Ubhaya Tantra and Yoga Tantra.

The Disciple Vehicle and the Self-Realized Ones Vehicle that were discussed yesterday are the primary vehicles for the attainment of liberation from cyclic existence. In relation to the three vehicles of the Disciples, the Self-Realized Ones and the Bodhisattvas, there are some sutras where the Buddha explicitly states that these three vehicles constitute final vehicles in themselves. In other words, the Sravaka or Disciple Vehicle constitutes the final path for some individuals for whom it is appropriate. The final realization of the Self-Realized Ones constitutes the final attainment for some individuals and similarly for the Bodhisattva Vehicle. However in other sutras, Buddha states that the Vehicles of the Disciples and Self-Realized Ones do not constitute a final vehicle or attainment because even those who attain the enlightenment of a Disciple or of a Self-Realized One will eventually enter the Bodhisattva Vehicle. All beings will ultimately attain Buddhahood. Even within the teachings of one and the same teacher, the Buddha Shakyamuni, one finds these conflicting statements with relation to these three vehicles. This underscores the point that I mentioned yesterday that the Buddha presented his teachings in response to the needs of specific individuals. For some beings, one set of teachings is more effective and beneficial while for others another set of teachings is more effective and beneficial.

This approach of adapting the Buddha’s message in response to individual inclinations and contexts has also been continued by subsequent Indian masters. For example in the Five Treatises of Maitreya, The Ornament of Mahayana Sutras, Maitreya teaches the standpoint where the three vehicles are presented as final vehicles in themselves. However in his Uttaratantra or Ratnagotravibhaga, The Sublime Continuum, Maitreya presents the opposing standpoint where the first two vehicles do not constitute final vehicles and the Bodhisattva Vehicle is the final vehicle. Similarly in Asanga’s writings, in his commentary on Maitreya’s Uttaratantra or Sublime Continuum, he explains Maitreya’s teachings primarily from the perspective of the Middle Way School or Madhyamika. However in his own text such as the Bodhisattvabhumi or The Bodhisattva Levels, he adopts the position of the Cittamatra or Yogacara School as presented in the Sutralamkara. So even in the writings of one Indian master, one can find different standpoints presented.

Now to go back to the text. Yesterday we finished the section explaining Kriya Tantra or Action Tantra. Now the second class of tantra is the Ubhaya Tantra Vehicle where ubhaya means both referring to both the external activity of rituals and so on and internal meditation. The text reads: The view of those who have entered the Vehicle of Ubhaya Tantra is as follows. Whilst there is no origination or cessation on the ultimate level, on the conventional level one visualizes oneself in the form of a deity. This is the same as it was for Kriya Tantra.

The text continues: This is cultivated on the basis both the practice of meditative absorption endowed with the four aspects as well as the necessary ritual articles and conditions. In the phrase “the meditative absorption endowed with the four aspects,” here the four aspects are identified in two ways in Jamgon Kongtrul’s commentary. In the first he identifies the four aspects to be the suchness of oneself (the practitioner), the suchness of the deity (the object of meditation), the suchness of mantra repetition and the suchness of the actual visualization of the meditation. In the second way, he states that these four aspects can also be understood as referring to sound (the mantra), mind (the meditative state), the self-generation of oneself as a deity and the generation of the other (the front-generation of the deity). So the phrase “the meditative absorption endowed with the four aspects” refers to these aspects. It is through the combination of the meditative absorptions and the reliance upon external conditions such as rituals that this particular form of yoga is achieved.

Jamgon Kongtrul in his commentary goes on to explain that although in some texts there is mentioned for Kriya Tantra the visualization practice being only in the form of a front-generation, visualizing the deity in front of oneself and seeking blessings. In this form there is no practice of generating oneself as a deity but he explains that this must be understood in terms of the differences between the principal and secondary Kriya practices. In the principal Kriya Tantra meditation, certainly one must have the meditation of generating oneself as a deity. In the secondary practices of Kriya Tantra deity yoga the blessings take the form of visualizing the deity in front from whom one then visualizes receiving blessings. But the principal deity yoga practice of Kriya Tantra must contain a practice where the practitioner generates themselves into the deity.

This is in agreement with the explanation of Kriya Tantra found elsewhere where there is an identification of six forms of deity yoga meditation in Kriya Tantra. These include the empty deity, sound, letter, form, seal and sign. In the Tibetan tradition there are many meditation practices, deity yoga meditations that belong to the category Kriya Tantra or Action Tantra. However with relation to the second class of tantra, which is Action or Carya Tantra, apart from the Vairocana-Abhisambodhi, there are very few [Carya Tantra] deity yoga practices in the Tibetan tradition. I have been told that in Japan there are quite extensive Carya Tantra practices including the Vairocana-Abhisambodhi and the Vajradhatu practices. These two are very prominent in the Japanese tantric tradition the lineage of which came from China.

Next are the Yoga Tantra Vehicles and the text reads: The view of those who have entered the Vehicle of Yoga Tantra is two-fold: 1) the view of outer yoga, the tantra of the sages and 2) the view of the inner yoga, the method tantra. The distinction between the two yogas here, the inner and outer yogas, is made on the basis of the approach of their practitioners. In the case of outer yoga, although unlike Kriya and Ubhaya Tantra, here the emphasis is mainly on the internal yoga of mental concentration and not reliance upon external conditions of rituals, articles and so on. However in common with the other two lower tantras, in the outer yoga one still does use the external conditions such as rituals and articles, including the practices of purity, but the main emphasis is on the internal yoga of meditative absorption. The difference is that in outer yoga, the state or level of mind that is used for one’s meditative absorption remains on the gross level of consciousness.

In the inner yoga, not only is the practitioner totally independent of depending or relying upon external means such as ritual practices and so on, but also the level of mind that is used in the meditative absorption is subtler. It is therefore referred to as the method tantra where here method refers to the methods and techniques used in bringing about the experience of the subtle level of consciousness. Such methods include the yogic practices of focusing upon the channels, the energy winds or prana and the bodhicitta drops. It is through employing these methods that the practitioner brings about the experience of the subtler level of consciousness which is then utilized to engage in the meditative absorptions. So the difference between the outer yoga and the inner yoga is made on the basis of whether or not the level of mind used in the meditative absorptions is gross or subtle.

In Jamgon Kongtrul’s commentary he explicitly states that it is only in the inner yoga where one finds the approach of the two stages of generation and completion. This provides a complete method for the practitioner to bring about the attainment of the two bodies of a Buddha, the Form Body or Rupakaya and the Truth Body or Dharmakaya. Therefore he explains that in many Vajrayana scriptures there are explicit statements that it is only by relying upon the practices as presented in the unique teachings of Highest Yoga Tantra or Anuttarayoga Tantra that one can attain the full enlightenment of Buddhahood. So therefore the practices of Highest Yoga Tantra are referred to as highest yoga or anuttara or unsurpassed yoga as they are unsurpassed in the sense that it is only in these teachings that the complete method or path for the attainment of the Dharmakaya and Rupakaya is found. The reason for this is that it is only in the teachings of Highest Yoga Tantra where teachings are explained whereby one can utilize the innate mind of clear light, the ever-present innate mind, transforming it into the path.

Many of the grosser levels of mind are adventitious or occasional; they do not last. They arise and then cease to exist, fluctuating and so they are occasional and adventitious. The yoga which is cultivated with the grosser levels of mind therefore cannot be lasting so therefore it is incomplete. In order for the yoga aimed at the attainment of the two bodies of a Buddha to be comprehensive and fully effective, that yoga must take place using the subtlest level of one’s consciousness referred to as the innate mind of clear light. It is only in the Highest Yoga texts that the methods for transforming the innate mind of clear light into the aspect of the path are explained. Therefore these practices are referred to as yoga, meaning the indivisible union of method and wisdom. They are also referred to as anuttara meaning unsurpassed because it is only in the Highest Yoga teachings that the method for effecting the innate mind of clear light into a meditative absorption, into a path are found. Therefore Jamgon Kongtrul explains this very clearly in his commentary to this text, making the distinction between the outer yoga tantra and the inner yoga tantra along the lines of whether or not one finds the techniques and practices for turning the innate mind of clear light into the path.

The text reads: The view of those who have entered the Outer Yoga, the sage’s tantra is as follows. Not holding the external ritual articles to be of primary importance, they cultivate their goal on the basis of emphasizing the yoga of visualizing male and female deities who are devoid of ultimate origination or cessation and the Form Body of the Noble One that share resemblance with them, which is the meditative absorption endowed with four seals (mudras) of a thoroughly purified mind. This reference to “visualizing male and female deities who are devoid of ultimate origination or cessation” is not simply a statement that these deities are by nature devoid of origination or cessation but rather to emphasize the need to cultivate the understanding and realization of these deities as being devoid of any ultimate origination or cessation as explained before. It is this wisdom realizing emptiness that is then imagined as arising into the form of a deity.

In the Outer Yoga, which is Yoga Tantra, the meditative absorptions are endowed with the four seals. These four seals correspond to the body, speech, mind and action. The Outer Yoga practice is modeled upon a process of purifying one’s body, speech, mind and actions. In relation with one’s body, speech, mind and action, four seals are mentioned which are the pledge seal, the dharma or reality seal, the action seal and the great seal. It is through the meditative absorption endowed with these four seals that the yogic practitioner goes through the process of purifying body, speech, mind and actions. This prepares the practitioner to then attain the body, speech, mind and actions of an enlightened deity.

One of the characteristics of Yoga, Performance or Outer Tantra as it is called here, is its tremendous emphasis placed upon mudras or hand gestures which are part of the meditation ritual. Many of these mudras are very complex so that there are very few experts who are completely knowledgeable of these intricate hand gestures or mudras. In fact once when I was giving the transmission of the Vajradhatu, the principal Yoga Tantra, I needed to rely upon a ritual expert who sat next to me guiding me so that I could form the mudras appropriately. He was like a shepherd guiding me. On another occasion when I was giving one of these teachings, the abbot of Namgyal Monastery who was a great expert on these mudras, was sitting to the side of me and while I was making these mudras I needed to watch him all of the time. This went for so long that I started getting a cramp in my neck so I finally asked him to sit in front of me so that I didn’t have to strain my neck.

Now the text moves on to the Inner Yoga which reads: The view of those who have entered the vehicle of Inner Yoga, the method tantra is three-fold: 1) the mode of generation, 2) the mode of completion and 3) the mode of great completion or perfection. In his commentary, Jamgon Kongtrul explains that the distinctions between these three modes should not be confused with the general distinction between the Mahayoga generation, the Anuyoga completion and the Atiyoga great completion or great perfection as is found in the general explanation of the Dzogchen teachings. Here the distinction is not exactly the same as the one found in the general explanation of the three stages of generation, completion and the great perfection of the Dzogchen teachings.

Jamgon Kongtrul in his commentary then goes on to explain that when generally speaking the two stages of generation and completion, the Tibetan scholars/masters have two primary standpoints. First is the standpoint of Rapjampa Longchenpa (1308-1363) and his disciples where Jamgon Kongtrul is referring to the two Kun mkhyens, the first being Longchenpa Rapjampa and the second Kun mkhyen Jigme Lingpa (1730-1798). The pairing of these two with Jigme Lingpa as a disciple of Kun mkhyen Longchenpa does not imply that he was an immediate or direct disciple as Jigme Lingpa lived much later. But in his biography, it is mentioned that once when Jigme Lingpa was meditating at Samye Chimpu Monastery, he had a mystical visionary experience of receiving direct blessings and inspiration from Longchenpa. Therefore Jigme Lingpa is sometimes referred to as the disciple of Longchenpa. According to them the distinction between the generation and completion stages is made on the basis of the two aspects of deity yoga meditation, the aspect of appearance relates to the generation stage and the aspect of emptiness relates to the completion stage.

Jamgon Kongtrul then goes on to say that the most excellent way of making the distinction between the two stages is the one found in the writings of Locen Dharmashri (1654-1717) which also happens to be the position of Tsongkhapa as well. Here the distinction between the two is made on the basis of whether or not the individual practitioner has been able to generate the wisdom that is the union of bliss and emptiness on the basis of the entry, abiding and dissolution of the prana winds within the central channel. All subsequent experiences of yogic meditative states which arise following the entry, abiding and dissolution of the prana winds in the central channel, this stage is referred to as the completion stage. All prior experiences of deity yoga meditation or visualizations are described as belonging to the generation stage.

Because of this, the generation stage is sometimes referred to as the contrived yoga as it is a simulated form of yogic states whereas the completion stage is referred to as the uncontrived yoga because the experiences are not simulations. So the distinction between the two stages is by emphasizing that the one is contrived and the other uncontrived. Jamgon Kongtrul goes on to explain that this is the most excellent way of understanding the difference between the two stages.

However Jamgon Kongtrul in his commentary goes on to explain that the distinction between the three modes mentioned in this particular text is completely different [from that just outlined]. Here the modes of generation, completion and great completion refer to various stages of a single deity yoga meditation. The deity yoga meditation here is described in terms of what are called the three meditative absorptions. The first is referred to as the meditative absorption of suchness, the second is the meditative absorption of the appearance of everything and the third is the causal meditative absorption. These three meditative absorptions correspond respectively to Dharmakaya meditation, Sambhogakaya or the Buddha Body of Enjoyment meditation and the Nirmanakaya or the Buddha Body of Perfect Emanation meditation.

The process of engaging in these three stages of meditative absorptions belongs to the mode of generation according to this text. The culmination of this process, which is the actual visualization of the complete deity, is referred to as the mode of completion as one has completed the process of generating oneself as a deity. Having completed oneself as a deity there are other practices such as visualizing other deities on specific points in the body such as the body mandala and these constitute then what is referred to in this text as the mode of great completion.

The text continues: The mode of generation is achieved by means of the meditative practice of gradual development of the three meditative absorptions, which were just explained, and gradual creation of the mandala. The mode of completion is achieved by abiding unwaveringly within the visualization of male and female deities that are ultimately devoid of origination and cessation as well as the middle way of ultimate expanse which is the nonconceptual truth, while on the conventional level cultivating a perfect equanimity and an un-muddled manner, the form of the noble deity with clear visualization.

The reference to the ultimate nature of reality called here in this text the “ultimate expanse” is to be understood in its proper context. Since we are dealing here with the context of Highest Yoga Tantra or Anuttarayoga Tantra, the reference to terms such as ultimate expanse, ultimate truth (paramārtha-satya), dharmadhatu and so on need to be understood in accordance with Anuttarayoga Tantra explanations.

So here ultimate truth or emptiness needs to be understood on two levels. The first level is objective emptiness which is the ultimate truth as explained in the Middle Way philosophical texts. This is emptiness as understood in the Perfection Vehicle. The ultimate truth or the ultimate expanse in the Vajrayana context also includes the second dimension, the subjective dimension or the subjective experience of emptiness. This is not referring to any subject but a unique subject which is the experience of emptiness at the level of the innate mind of clear light. The innate mind of clear light is the subject that realizes emptiness which is also referred to as the ultimate truth or the ultimate expanse. This is described as a nonconceptual truth and it is in this context that one needs to understand the meaning of the term ultimate expanse in the context of Anuttarayoga Tantra.

This is described differently within the different lineages. For example in the Kagyu lineage of Mahamudra, this union of objective emptiness and the subjective clear light is called the indivisibility of emptiness and awareness (rigpa byerme SP?). In the Sakya lineage, this is called the indivisibility of emptiness and luminosity/clarity. In the Sakya Lamdre cycle, clarity is said to be the defining characteristic of mind and emptiness is said to be the nature of mind and it is the union of these two that is understood to represent the ultimate nature of reality. So in the Lamdre this is called tsel stong shung drup (SP?) or the unity of emptiness and clarity. In the Gelug tradition, this is described as the indivisibility or union of emptiness and bliss where emptiness here is the objective emptiness and bliss refers to the great bliss of the innate mind of clear light. Similarly in the Dzogchen teachings of the Nyingma tradition, because of their distinction between ordinary mind and basic awareness or rigpa which is described as pure and pristine cognition, they speak of primordially pure reality and its nature of compassion so for them it is the union of primordially pure reality and compassion.

So when this text speaks of the ultimate expanse, this is from the context of Highest Yoga Tantra, representing the nonconceptual truth, one needs to understand this ultimate expanse in terms of the union of emptiness as explained in the Madhyamika writings with the subjective experience of clear light fused with that emptiness. The text goes on to say the “origination and cessation as well as the middle way of ultimate expanse which is the nonconceptual truth” and this also alludes to the understanding of how the entirety of phenomena comes into being as the result of the play of the ultimate expanse.

For the next stage the text explains: The mode of great perfection is to meditate on the basis of the understanding all mundane and supramundane phenomena, all worldly and trans-worldly phenomena, as being devoid of any differentiation and recognize as always having been present as the mandala of body, speech and mind. In the language of the Guhyasamaja Tantra, one will understand the entirety of origination of all factors of both cyclic existence and nirvana as the manifestation of the activity of the innate mind of clear light as either the sequential processes of arising or the reversal process of dissolution. For example in the Guhyasamaja Tantra literature, one can find explanations as to how the entire element of cyclic existence, of the afflicted world of samsara is a product of the activity of karma and the prana winds propelled by the karma. Underlying this is the activity of what is called the Eighty Conceptions indicative of the various levels of consciousness and these Eighty Indicative Conceptions are in turn the grosser level of manifestation of subtler states of consciousness such as the appearance, increase, great increase and near-approximation or near-attainment and these three states of subtle consciousness give rise to the Eighty Indicative Conceptions. In turn, these three subtle states arise from the fundamental, innate mind of clear light which is the fundamental state of mind which remains ever-present and enduring. From this point of view, at times this innate mind of clear light is also described as unconditioned, unconditioned by temporary causes and conditions. So in terms of its continuity, it is ever-present and is also called the unborn nature.

In the Guhyasamaja Tantra literature language, one can find a description as to how the entire world of samsara and nirvana are in some sense the play, the constant play or manifestation or a resonance of the fundamental innate mind of clear light. When seen from this point of view of the clear light then there is certainly no distinctions to be made between samsara and nirvana or the unenlightened and enlightened states.

As far as the equality of samsara and nirvana is concerned, one also finds references to this even in the sutra teachings as well. For example, there is a passage in Maitreya’s Abhisamayalamkara or the Ornament of Clear Realization where he states the equality of existence and the transcendence of existence. Similarly in Nagarjuna’s Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way, one can find explicit statements of the equality of samsara and nirvana. However in these sutra writings, the equality of samsara and nirvana are understood from the point of view their ultimate nature of reality as both being empty. In the Vajrayana context however, the equality of samsara and nirvana has the added meaning of how the entirety of factors for both samsara and nirvana can be understood in some sense as the constant play or manifestation of the subtle mind of clear light.

The text then goes on to read: It is stated in the tantra:

As for the limbs of the vajra body

They are known as the Five Buddhas.

The sources and the numerous elements

They are the mandalas of the bodhisattvas.

Earth and water are Locana and Mamaki;

Fire and water are Pandaravasin and Tara;

Space is Dhateshvari.

So the three worlds are primordially pure.

So all phenomena of cyclic existence and nirvana are primordially unborn yet they have the capacity for illusory function as they have always been in the nature of the ten Tathagatas and their consorts. This reference of all phenomena of cyclic existence and nirvana as being primordially unborn does not imply that they do not come into being due to their causes and conditions. Here being primordially unborn refers to the perspective that from the point of view of the innate mind of clear light, because they are all in some sense manifestations or the effulgence of the innate mind of clear light. Therefore in that sense they can be referred to as unborn.

The text continues: All phenomena are therefore naturally transcendent of sorrow. This indicates that all phenomena are in some sense primordially pure and this is sometimes referred to as primordially enlightened or they are primordially Buddhas. This is because so far as the clear light nature of the mind is concerned, its nature is always pure; it is the afflictions and the various defilements which co-exist with it but they do not penetrate into the essential nature of the clear light mind itself. So as far as the clear light mind itself is concerned, it is pure and so from that point of view, all phenomena, which arise from it, can also be described as being primordially pure and of being primordially in the nature of Buddhahood.

The text continues: The great elements are in the nature of the Five Consorts, the five aggregates in the nature of the Five Buddha Families, the four consciousnesses in the nature of the four great bodhisattvas, the four objects as the four beautiful goddesses, the four senses as the bodhisattvas, the four temporal stages as the four goddesses, the bodily organs as the consciousnesses, the sensory fields and the bodhicitta drops arising from them as the Four Wrathful Deities, the four extremes of eternalism and nihilism as the four female wrathful deities, the mental consciousness as the nature of Samantabhadra, namely the indestructible bodhicitta, the objects of both conditioned and unconditioned phenomena are in the nature of Samantabhadri who is the receptacle of the creation of all phenomena. All of these in turn have already been in the nature of complete enlightenment (as explained before); they are not now acquired by means of the path. This refers to the natural enlightenment which is the fundamental innate mind of clear light because that is ever-present; it is not brought into being as the result of the path.

Thus all phenomena, conditioned and un-conditioned such as the ten directions, the three temporal stages, the three worlds and so on do not exist apart from one’s own mind. The reference to these not existing apart from one’s own mind should not be understood in terms of the statement of the Buddha in the sutra text where he states how all phenomena are one’s own mind. Here it refers to how all phenomena are manifestations of the innate mind of clear light.

The text continues: It is stated:

The clear understanding of one’s own mind –

This is the Buddhas and the bodhisattvas;

This constitutes the three worlds;

This constitutes the great elements as well.

Thus it has been stated:

All phenomena dwell in the mind; the mind dwells in space, while space dwells nowhere.

Space here does not refer to external space as we conventionally understand it but space here refers to an inner space which is again the clear light. Since the clear light is ever-present, it develops nowhere.

Furthermore,

All phenomena are devoid of an intrinsic nature; all phenomena are thoroughly pure from the very beginning; all phenomena are thoroughly radiant; all phenomena are naturally transcendent nirvana and all phenomena are manifestly enlightened.

This then is the meaning of Great Perfection. In the commentary at this point, Jamgon Kongtrul summarizes and states the conclusion that in this context when one reads the term jñana or transcendent wisdom, one should not understand it in terms of any other form of knowledge/wisdom but understand it in terms of the mind of clear light. Similarly when one finds references to the term the self-resonance of something, one should not understand it purely in terms of the resonance of any thing but rather the resonance of the mind of clear light. He then goes on to explain that in the Dzogchen literature, the clear light is sometimes described as being unconditioned. Here this meaning of unconditionedness is not the same as the characterization of permanent phenomena as being unconditioned such as the mere absence of something like space is defined as the mere absence of obstruction; this is not the meaning here of unconditionedness in the context of the Dzogchen teachings. Unconditionedness in that context refers to the clear light mind being unconditioned by any temporary causes and conditions or any other fluctuating adventitious causes and conditions.

He then goes on to substantiate his own understanding of these teachings and concepts by citing from Saraha, the great Indian yogi, he also cites an Old Translation tantra and finally he cites a tantra known as Grol ba’i thig le or the Drop of Liberation or the Liberating Drop which is a New Translation tantra. In all of these citations, explanations are given as to how the emergence or evolution of the entirety of the phenomena of cyclic existence and nirvana can be understood as manifestations arising from the innate mind of clear light. Kongtrul Rinpoche then refers to the explanations found in the Guhyasamaja Tantra, as explained before, how the entire process of coming into being of cyclic existence can be understood in terms of the function or activity of the Eighty Indicative Conceptions which themselves arise from the three progressively subtle states of consciousness called appearance, increase and near-attainment, all of which arise from the innate mind of clear light. It is from the arising and dissolution from this mind of clear light that one needs to understand the origination of cyclic existence or samsara.

He then goes on to explain that when one says that the entirety of phenomena is a manifestation or play of the innate mind of clear light, one does not need to prove that all everyday objects such as vases, pillars and so on are somehow manifestations of this. Rather the meaning here is that in so far as an individual sentient being is concerned, their experience of the entire world of phenomena arises from the previously mentioned process. Karmic prana winds arise from their previous karmic actions, which in turn give rise to progressively grosser levels of consciousness culminating in the Eighty Indicative Conceptions which themselves give rise to the afflictions which then motivate the individual to perform actions and the actions set in motion the chain of causation within cyclic existence. So as far as the individual is concerned, it is in this manner that the entire cosmos is a function of the innate mind of clear light.

So here one can understand that if one examines the language of the Guhyasamaja Tantra, one will find that sometimes the innate mind of clear light is described as the Basic Dharmakaya or the Foundational Dharmakaya. The term Basic Dharmakaya suggests that the entire process is understood in terms of some sort of analogous process of the arising of the Three Kayas: the Buddha Body of Reality, the Buddha Body of Perfect Enjoyment and the Buddha Body of Perfect Emanation. These also have correlations with one’s day-to-day experience of the periods of wakefulness, deep sleep and death. Because of this in these tantras, one will find specific meditative practices called the “mixings” which are aimed at mixing one’s experience with the states of wakefulness, deep sleep and death.

Jamgon Kongtrul then goes on to explain an analogy of how all of the dreams that one experiences are in some sense manifestations of one’s sleep as they arise from the state of sleep. In a similar manner one can understand the arising of the entirety of the phenomena of cyclic existence as coming out of the innate mind of clear light. In the commentary, he then states that for detailed explanations of these topics one should consult the great commentarial treatises on the tantras.

In the Sutra System of teachings one finds references to what is called the natural nirvana and the non-abiding nirvana where natural nirvana refers to the emptiness of all phenomena, the ultimate nature of reality which is naturally pure, naturally devoid of any grasping at intrinsic existence. Non-abiding nirvana refers to the individual who has not only realized this natural nirvana but who has also purified all of the defilements which are the adventitious obstacles. By clearing all of these, one attains the non-abiding nirvana of a Buddha.

In a similar manner in the Vajrayana context of Highest Yoga Tantra, mentioned is made of the naturally pure wisdom or naturally pure jñana and the thoroughly pure jñana. The naturally pure jñana refers to the innate mind of clear light that each of us all naturally possess because its essential nature is unpolluted and so from that point of view, it is naturally pure jñana or wisdom. Once the individual through the practice of the path gains total liberation and Buddhahood then at that point, not only is the clear light mind of that individual pure but also that individual is free of all of the adventitious defilements therefore at that point this individual’s mind of clear light can also be referred to as the thoroughly pure jñana. So such terms are also found in the Vajrayana texts. We will stop here.

The Muktitilaka is a tantric commentary written by Buddhaśrījñāna (Buddhajñānapāda) http://kalachakranet.org/teachings/Com-Rosary%20of%20Views-HHDL.pdf