His Holiness the Dalai Lama: The merit we accumulate from these practices should then not be dedicated to our own well-being, freedom from samsara, existence in higher realms and so on, but solely to the attainment of buddhahood in order to relieve the suffering of others. We must also have the wisdom to see the void of the existence of the triad. This constitutes the 37th practice.

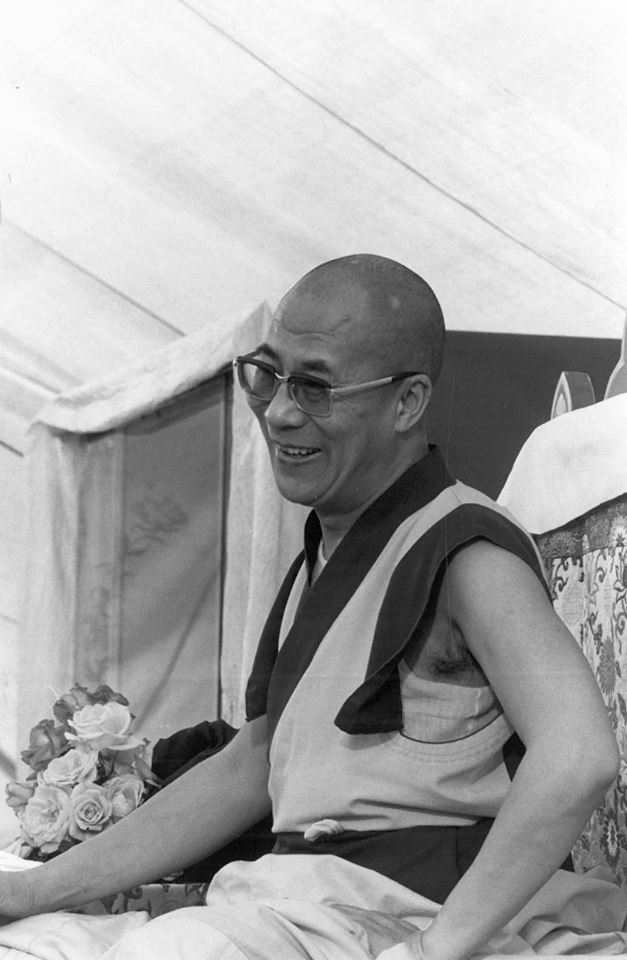

4 – The Thirty-Seven Practices of the Bodhisattvaby His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Bodhgaya 1974.

Once we have taken birth in bondage, everything else follows automatically. We all suffer the fruit of the past. The intrinsic nature and cause of samsara are impure because it is a product of karma and delusion, which it in turn produces. It is always endowed with suffering, karma and delusion—circumstances always cause delusion to arise. There are, therefore, five wrong qualities of birth: birth with suffering, birth in the wrong place, birth reproducing the same errors in the future, birth into a state of suffering and delusion, birth taken without freedom of choice.

Until we can free ourselves from this existence, this production of karma and fruit prevents any true, permanent happiness. So we must try to free ourselves from this plight by practicing the threefold training of morality, wisdom and meditation, with morality as the base. By our practice we must destroy delusion, the cause of all our trouble, by the force of antidote. So we must strive to attain nirvana.

The ninth practice of the bodhisattva:

Happiness is like dew on the tip of a blade of grass, short-lived and bound to vanish. Therefore we must seek the supreme stage of nirvana which never changes into suffering – this is the practice of the bodhisattva.

The tenth practice of the bodhisattva:

From time immemorial we have been cared for by others with motherly love. If they remain in samsaric suffering how cruel just to free ourselves! To save them and other countless beings, produce bodhicitta, the wish for buddhahood – this is the practice of the bodhisattva.

These verses express the essence of Mahayana Dharma. In short, all the infinite sentient beings share the wish to avoid suffering and obtain happiness. To seek solely one’s own happiness therefore is reprehensible. From time immemorial we have always been concerned solely with our own happiness, yet what good has it done us since we still suffer!

As it is said in the Guru Puja, “The chronic disease of holding oneself dear is very harmful, preventing us from working, walking or eating properly; we are half a body, half a person. As long as we are self-cherishing, we are like half a human being.” Therefore we must do our best to get rid of this disease, and in the Wheel of Sharp Weapons, a mind-training text, this self-cherishing is particularly attacked, it is called an evil ghost or demon. An external worldly demon does temporary harm to us, but the inner demon harms us all the time. The truest demon is attachment to self, grasping by the self, ignorance, then the self-cherishing attitude. From this demon arises “I want this” and “I want to be happy”; ignorance and self-cherishing reinforce and support each other.

Were these the only two demons we have to cope with, it would not be too bad, but usually others like jealousy, wandering thoughts, drowsiness in meditation, and so forth, arise. So being a true practitioner of the Dharma is not easy, he is like a true soldier always fighting the enemy within—delusion. The demon of selfish grasping is the great enemy we have to fight. Sometimes this is very difficult and one may get discouraged. Naturally there are times when we have to face many problems, but we should not lose heart but struggle on until we obtain final victory. It is impossible to defeat all our worldly enemies, but this most glorious victory over the enemy within is possible. As Nagarjuna puts it, “There has never been anyone who has defeated all his worldly enemies and passed away peacefully.” Which is very true. But we can defeat the enemy within and do so once and for all. As the Bodhicaryavatara says, “All our worldly enemies can be temporarily defeated but they will regroup and attack again. But the enemy within can be defeated forever.” To fight with the true enemy, our delusions, is the responsibility of the practitioner. Ben Kungyel says, “My practice is to stand at the door of delusion with the spear of the antidote raised. If he is fierce, I am also fierce.”

The practitioner of Dharma cannot be lax in this respect. Therefore, it is not at all easy, but we should not let ourselves be discouraged. Unlike bodhicitta and shunyata, self-cherishing has no firm foundation. It is not only that the attitude of holding others dear and shunyata has a solid foundation, but all the buddhas and bodhisattvas are backing this, giving power and energy to their supporters. Though there may be marasfostering self-cherishing through ignorance, those who support us are enlightened. So on the one side there is unsteady backing and on our side indestructible support on firm foundations. As the Bodhicaryavatara says, “It is the buddhas who have thought and contemplated for kalpas on bodhicitta, which is the essential thing for all sentient beings.”

Thinking in this way, though our standard, our ability, is poor and weak, we have many reasons for confidence in our victory. Even though egoism and self-cherishing seem strong they are without foundation. One reason is that the most subtle consciousness arising in us can be transformed into a realization of shunyata—delusions cannot survive indefinitely. So we should not be discouraged but struggle against self-cherishing and eliminate completely this chronic disease. And we must develop the attitude of cherishing others by realizing the great qualities.

As it says in the Guru Puja, “Seeing that the mind which tries to lead others to happiness is the door from which enter all the infinite qualities, although these beings may rise against me as enemies, bless me to be able to hold them dear, even dearer than my life.” The mental attitude of holding others dear is the supreme medicine, the ambrosia of the inner guru and master. Realizing this fact we must generate such a mind where none exists and develop it where it does. Do this in all actions, walking, sleeping, and thinking. If we can do this we become a supreme practitioner of Dharma, drawing on the essence of life, making a supreme offering to bodhisattvas, and using the supreme method to rid ourselves of obstacles. There is nothing higher or greater than such a mind.

“If therefore from time immemorial we have been cared for with motherly love …”

The eleventh practice tells us that by seeing the wrong of self-cherishing and the virtue of cherishing others, we should exchange our happiness for their suffering.

The twelfth practice of the bodhisattva:

Whoever steals our wealth or lets others steal it, may we dedicate to him our wealth, body and merit – this is a practice of the bodhisattva.

This also involves the exchanging of self, and I will now point to some particular practice of this. For example, if somebody from intense greed robs us or encourages others to do so, he greatly harms us, at the worldly level, and may therefore become an object of hatred, and, legally, we have every right to retaliate. But for one who practices bodhicitta to react in that way is quite wrong. Instead we should dedicate to him not only our possessions but also our body and merit from past, present and future lives. A case in point is the author of these thirty-seven practices. He was in Sakya, and had just left a monastery where he had received offerings. On the road he was stopped by thieves who took everything from him and ran away. Very peacefully he called out after them, “Wait!” They stopped and he explained that he had asked them to do so because he had not had time to dedicate their spoil to them properly. He then made a very slow and complete dedication. They returned the property and, after receiving his teaching, became his disciples.

The thirteenth practice of the bodhisattva:

Although innocent of any offence, even if someone threatens to kill me, I must, by the power of compassion take upon myself all the sin of that person – this is the practice of the bodhisattva.

This is another very difficult point and situation. One is completely innocent oneself and yet someone else from jealousy or some other reason wants to harm or even kill us. Yet even towards such a person we should not react with hatred but should generate strong compassion. Out of great compassion we must practice taking upon ourselves his unskillful deeds, while giving him our merit.

The fourteenth practice of the bodhisattva:

Then there is the case of someone that slanders me, spreads unpleasant stories about me throughout the length and the breadth of the world. But I, out of a loving mind, must praise his qualities in return – this is the practice of the bodhisattva.

From dislike, desire to abuse us, debase us, someone spreads bad reports about us, though we are totally innocent ourselves. Of course, at a worldly level we should try to establish our innocence and thus defeat him. But from the point of view of the bodhisattva path, we must respect and praise his qualities.

The fifteenth practice of the bodhisattva:

Though someone may deride and speak bad words about you in a public gathering, looking on him as a spiritual teacher, bow to him with respect – this is the practice of bodhisattvas. 1

This clearly is a case of someone that dislikes us and wants to hurt us by showing off our faults in an unpleasant way, bringing a flush to our cheeks…

You should protect your heads from the sun. Put your robes over your heads, like “yearlong meditators.” When I was a boy I played a game with squares designed to show a child the stages of spiritual progress, and one square showed a “yearlong meditator” with his robe over his head. Now you can look like him!

We must respect someone who does this for making us do a self-criticism, he is a very helpful person. We do not see our own faults clearly, someone who helps us to do so is like a great guru, and we should respect him as such.

As scripture does, a guru instructs us and points out our faults. The Dharma is a mirror to show us our faults and accordingly how to correct them. We discover our impurities of body, speech, and mind by looking into the mirror of Dharma. So someone who discovers our faults instructs us as well as a guru. As the gurus and Tibetans say, “Praise is good, but criticism is better,” as criticism shows up our faults, and if we suffer from it we remember Dharma. Praise may kindle pride and make us forget our faults, while criticism teaches us not to commit the same faults again. In the same way happiness is good but suffering is better, because it takes us to the Dharma. Happiness eats the fruit of our past merit.

The sixteenth practice of the bodhisattva:

Someone we have taken care of like a son, and who then treats us like an enemy, we should love particularly dearly, as a mother does a sick child – this is the practice of the bodhisattva.

As in the Eight Verses on the Training of the Mind, “When a person I have benefited, and placed great hopes in, hurts me very badly, may I regard him as my supreme guru.” With so much sacrifice, love and care it is natural, and seems almost obligatory, that such a person should be kind to us, and then he does quite the opposite and treats us like an enemy. Another example would be a child afflicted with a bad spirit who attacks his mother with a knife. The mother should do everything to separate her child from that bad spirit and to show her child even more loving care. We cannot hate a child or a man with a knife, because they are driven by delusion. These are very difficult but essential practices and have to be singled out.

The seventeenth practice of the bodhisattva:

If someone equal or inferior to us in attainments insults us, we should be humble towards him and respect him as a guru – this is the practice of the bodhisattva.

This is really very beneficial. I do this sometimes. If someone upsets or disappoints us, makes us feel very angry, one should sit and meditate, mentally recite the verse from the Eight Verses on Training the Mind, “Whenever I am in the company of others may I think myself the lowest of all and hold the others supreme in my heart.” One should visualize oneself bowing to the other person, respecting and praising him. If we do this it is very helpful, we are the humblest of all. Servants of all other sentient beings, we bow to them. Previously, visualization would have brought hatred, but if we respect this practice it will subdue hatred. Therefore, as the practice says, instead of visualizing an enemy whom we hit, visualize bowing respectfully to him. If you feel shy about this, do it in a corner, and then if you meet him in the street pretend that nothing is the matter. The whole purpose of this is to tame and train the mind, to bring it the peacefulness we need.

The next verse refers to two of the great obstacles of Dharma practice. The first is when everything in our life is fine, the second when we feel very despondent.

The eighteenth practice of the bodhisattva:

When we are badly off, abused by everyone, plagued with serious illness and in very low spirits, to never be downhearted but rather to take on ourselves the unskillful deeds of other sentient beings – this is the practice of the bodhisattva.

This is like the situation of the Tibetans losing their country, getting criticism from Indians, getting TB and feeling very despondent. “How can I practice Dharma under these conditions? I shall give up my robe, renounce my vows, go and get a lay job.” It is very easy for this kind of thought to come, and very easy to lose the Dharma this way. Although poor, while there is someone to help us, there is still hope. But let us assume there is no help forthcoming, and we are subject to abuse. Well, if your body is in good health, things are not bad. But let us assume that we are ill. If our mind is at peace, then this can be borne too. But let us assume our mind is troubled as well. In such a situation the practice of the bodhisattva will, if we are not careful, be lost. So we should in such times take upon us all the suffering of sentient beings, wish all suffering upon ourselves, and dedicate our efforts to them – this is a practice of the bodhisattva.

Another dangerous case is when matters are faring too well for us:

The nineteenth practice of the bodhisattva:

When one has a good reputation and the respect of many, with all the wealth of the God of Riches, see that such fruit of samsara is insubstantial, and do not take pride in it – this is the practice of the bodhisattva.

One may, for example, be very famous for one’s worldly knowledge, or knowledge of the Dharma, and be respected by all. One’s good qualities “hit the headlines,” and one is universally popular and respected, worshipped by everyone. One becomes so wealthy one doesn’t have to admire anyone, being one of the “top people.” This is another time when there is a real danger of ceasing to practice the bodhisattva path. We may have a very strong pride in our wealth and fame, know Dharma so well that we think, “I can outdo Nagarjuna.”

Being the object of great respect and praise, one can be misled into thoughts such as: “I could kill a man, it would not matter so much, like killing lice.” In criticizing and abusing others, all sorts of defects come, sitting there like an owl. One must be very careful of this. Tsongkhapa says, “Whenever people prepare for me a splendid seat, prepare for me a great offering, I have the presentiment that this is of the nature of suffering. I’ve had this habit for a very long time.” And he also pointed out that even great fame is not worthy of attachment. As it says in the Bodhicaryavatara, “Why is one so attached to praise? Because others criticize us. So why hate those who criticize, when others praise?”

We should not be attached to fame and praise, even a little mistake can spoil everything and we can easily become a target of criticism. The same holds true for wealth, which is one of the worst deceptions, a major source of trouble. By realizing the wrong qualities of all the various attainments of samsara, we will see their true value. As Dromtönpa said, “Though others may rate us very highly, the most expedient course is to see ourselves in the lowest rank.” I try to practice this, and do my best to put myself at the lowest level. This is in fact the most practical thing to do, otherwise considerations of hierarchy cause trouble and agitation. Whatever people say, to use my mind to practice Dharma is my own responsibility, to make it real Dharma. For even with a Dharmic outward form one can practice non-Dharma, so mindfulness is always important. And to keep the lowest station is the root of happiness.

Because of the nature of Tibetan society it is still easy to practice deep humility. In the West this is difficult because people take advantage of you. This is not the case in our society and it is therefore particularly important that those with great names, lamas or tulkus, must practice humility. To do this is to practice Mahayana Dharma. Otherwise we develop attachment to name and fame, which is a meaningless endeavor. Some people I know, who have little knowledge, act with great pretentiousness and I find this so futile that inwardly I cannot help laughing. So to be without pride is the practice of a bodhisattva.

The twentieth practice of the bodhisattva:

Unless hatred of one’s enemy is overcome, the more we defeat the outer enemies, the more such enemies will increase. So by the force of love and compassion to tame one’s mind – this is the practice of the bodhisattva.

This bears out what I have already said, that until we defeat the enemy within, even though defeating outer enemies, the latter will grow. As it says in the Bodhicaryavatara, “How can we find enough leather to cover the surface of the earth? With just a little bit of leather on the sole of our shoe, we’ll cover the whole earth.”

The wicked are as widespread as space, and can fill the sky; they cannot all be defeated. But defeating a hating mind is the same as defeating our outer enemies. We cannot hope to defeat all the harmful beings in the universe. But if we defeat our inner enemy of hatred we thereby defeat all bad beings. Otherwise the outer enemies increase more and more, as the Chinese Communists have been finding out.

From the point of view of Dharma what is wrong is that the real enemy within us has not been overcome. For example, politically we see that while we can have peace for one or two generations, it does not last. Cases in point are very clear. This was very clear with the Chinese from 1959 to 1969 and now in 1974. Nearly fifteen years have passed and trouble is increasing for the Chinese. One reason is that politics are very corrupt and deeply bad, but they are also like this because the source of this badness is within the individuals, within themselves they do not wish to leave people in peace. Therefore, “We have to defeat the enemy within by the force of love and compassion.” As Tsongkhapa puts it, “Without carrying weapons like bows and without wearing armor one can defeat single-handed the million-strong hose of Mara. Who else than you can fight such a battle?”

So we must defeat our inner enemy with the weapons and armor of love and compassion. There is a parallel in our society when we also have disputes and troubles, but meet together peacefully and non-aggressively. If we try to do something while keeping this aggression and anger in our minds nothing is really settled, a peaceful mind is essential. If we appear outwardly aggressive it is because we are not peaceful inside We have made the distinction between “them” and “us,” which means there is strong attachment to one side and strong aversion towards the other. If we use this approach to try and settle something it gets worse and worse. With a peaceful mind we can discuss matters with the right motivation and find a solution. If two people have hatred in their hearts, inevitably they clash. If they overcome it they are like new people. If their inner agitation can be damped down they can bring about harmony. To tame the inner enemy, one’s own mind, is a practice of the bodhisattva.

The twenty-first practice of the bodhisattva:

The nature of desire is like salt water. The more we drink, the more our thirst will increase, so to abandon the objects towards which clinging and attachment arise – this is the practice of the bodhisattva.

To enjoy objects of desire involving touch, taste, smell, hearing, sight and contact is like drinking salt water. The object of desire never gives satisfaction, the craving for more will always increase. So, all the pleasure or happiness that comes out of attachment is deeply not beneficial to us, and even harmful. For example, sexual pleasure appears immediately to us as happiness but deep down it is a cause of suffering. Like an itch on the skin, which it comforts us to scratch, but to say, “I would like to have itchy skin” is nonsense. To scratch an itch is pleasurable but to be without the itch is even better. In the same way samsaric desire is pleasure but to be without such desire is even better, as Nagarjuna says in his Precious Garment. Therefore the object of desire, however much enjoyed, never gives satisfaction, but goes on increasing desire. By seeing the falseness of desire, we must abandon its objects immediately, this is a practice of the bodhisattva.

The practices so far described relate to relative bodhicitta. Those that follow relate to absolute bodhicitta, the realizing of shunyata. The latter can be divided into two parts: space-like meditation and illusion-like meditation. This is not an absolutely clear distinction but it will serve.

The twenty-second practice of the bodhisattva:

All appearances are an illusion of our mind, which has since infinity been beyond the extremes of manifestation (existence and non-existence). By seeing this, and not conceiving subject and object as inherently existing – this is the practice of the bodhisattva.

The Vijnanavadins say that everything that appears and exists, all phenomena, are of the nature of mind, but Chandrakirti of the Madhyamaka says, “Everything that exists and appears does not exist by itself, but exists as seen by our relative mind.” This is relative existence, which is therefore not absolutely true. If things had an absolute way of existing in themselves, the more we searched for them, the clearer they should become. But in fact they slowly fade away until no base or starting point is found. This is not because they do not exist at all, since then we should not derive any harm or benefit from them. As we do, they exist, but their way of existing we fail to find. So it follows that they do not exist in themselves but through the subject, in the relative mind’s way of looking. Therefore, appearing to really exist, and this real existence not standing up to analysis, this proves that our way of perceiving is a delusion. As the Seventh Dalai Lama says, “The objects passing through the mind of a sleeping man are a dream, but it is only an appearance. There is no object on this base, it is only a mental image.”

If at this moment you are dreaming about being in Tibet, you know when you wake up that you were not in Tibet, that there is no Tibet on this basis. Similarly, oneself, others, samsara, nirvana, all existence, is only seen, only designated, by our act of naming and our knowledge. But its inherent existence never exists, not even as an atom.

So the phenomena seem to exist, when they appear, on that base. But in fact they do not exist at the place we point to. And yet, as regards objects of our sensory faculties, everything which appears to beings drugged with the sleep of ignorance seems to truly exist on that base. As the Seventh Dalai Lama says, “Look at our evil mind, see how it works.” Yet in fact this is the way in which phenomena exist, for beings like ourselves, deluded with the veil of ignorance, with their six faculties, whatever appears, more or less, one or many, seems to exist objectively just by our naming and knowledge of it. Everything is outside us, “Look, there it is! Over there! It is independent, standing by itself.” That is all nonexistent, yet this is how it appears. As the Seventh Dalai Lama says, “Thus ‘I,’ or anything else, this way of existing inherently, in itself, which appears to the deluded mind, is the subtle object of negation. To refute it from our mind is most precious.”

Therefore, everything that appears, pure or impure, exists relatively because of mind, in the relative vision of the mind. And even mind itself, included in all existence, we do not find it if we search for it in an absolute sense. Mind exists as a stream of moments of consciousness. Our “I consciousness” is always something there, vivid, in itself. If we divide up the stream and search, it does not exist; the whole does not exist separately from its parts. And a part cannot be a whole. The part and the whole are something different. After breaking it down, and taking away the parts, the whole cannot survive. The whole exists in the parts, yet when we search we cannot find it. We can’t say confidently “here it is.” Therefore, the mind has, since infinity, been beyond the extremes of inherent existence or total non-existence. It is just non-self-existent. And as the Seventh Dalai Lama says, “The base, samsaric and nirvanic existence, is always just a projection of our inner mind. And the mind also, if analyzed, is birthless and indestructible. The nature of the true way of existing is wonderful.” Therefore, all existence, samsara and nirvana, are of the nature of the mind and the mind itself is birthless and indestructible. And the being that owns the mind is also birthless and indestructible.

“I am a yogi of space without birth. Nothing exists, I am a great liar who sees all appearances, hears all sounds as a great illusion. The wonderfulness is the union of the appearance and the void. And I have found the certainty of undeceiving interdependence.” To this great liar of a yogi, all appearance and sound seem to exist and, at the same time, nothing exists. If everything had a real existence, there should never be a contradiction. But, for example, a tree in spring has fine foliage and blossoms, but at another time is bare and ugly. If its beauty really existed, it should always remain there, never change into ugliness. It is the same with people, who are at times beautiful, at times ugly. If their beauty really existed it should never change into ugliness. Also, our defiled mind, if it really existed, it could never be changed one day into a completely purified, omniscient buddha mind. But what is defiled can become undefiled. Ugly can become beautiful, which shows that nothing really exists. For real existence these changes are never possible. For a truly existing base the change of cause and effect can never be possible. But here is cause and effect, there is good and bad, so therefore these can only be applied to non-real existence. To real existence these qualities can never be applied. These opposites on one base provide the proof that it does not really exist.

Therefore the wonderfulness is the union of shunyata and the appearance. Things manifest themselves in various ways, but their true nature is empty of real existence and therefore they change according to circumstances. They can thus appear in various ways, which means that shunyatadoes not negate appearance and the latter does not negate shunyata. Because the nature of phenomena is shunyata, empty of real, permanent self-existence, they can appear in various ways, and vice versa.

My understanding of these questions is not very good, but I am trying to improve. These are very difficult issues and we have to accustom our minds to them. Sometimes we should meditate on shunyata, sometimes on appearance and do so in a balanced way, and hopefully one day shunyata and appearance will arise in our mind as supporting each other, “the wonderfulness of the union,” as the guru called it whose name I can’t remember. What I wanted to convey was that if all phenomena exist in themselves, independently, permanently, they should always exist in that way. But when we analyze matters correctly, we find things do not exist at all in that way. If this definite certainty comes to our mind, this previously vivid way of existence suddenly collapses without support, falls away. Previously seeming to have strong support, it suddenly dissolves and has none. In the depth of our mind we will be able to swear to this certainty if we keep our mind dwelling very softly on the collapse of this appearance. If our power of concentration is not good, we cannot do this for long, but even a short moment is good. In that short moment, the vivid way collapses, and just the negation of real existence is left. At that time there is no chance for any other manifestation in our mind.

“By ceasing to conceive all the manifestations of subject and object, having no other manifestation, keep in this shunyata, see, realize the nature ofshunyata .” “Un-seeing is the supreme seeing.” Therefore to keep our mind in this blankness, negation and shunyata, this is called space-like meditation. Illusion-like meditation is for dealing with relative phenomena from post-meditation, after shunyata meditation.

The twenty-third practice of the bodhisattva:

When we encounter something attractive which pleases the mind, to see that it is like a rainbow in summer, and though it appears beautiful, not to regard it as anything but ephemeral, and thus to abandon clinging and attachment to it – this is the practice of the bodhisattva.

The purpose of realizing shunyata is to know the proper way of coping with existence. When we realize it we see the true nature of all phenomena, their actual way of existing, and then understand that our usual way of knowing them has been false and deluded. When we realize the falsity, we know how to respond accordingly. If we know how to deal with something that appears to be other than it is, then we won’t be deceived.

When we realize shunyata, this does not mean that we reject all appearances, and mentally deny them. Its purpose is to stop this exaggeration of the object by ignorance when it appears to our mind—imparting to it real existence—and thus stop strong attachment and hatred. I believe that must be its purpose, which is certainly very beneficial. In space-like meditation we meditate on shunyata, afterwards the idea is not to reject everything, but to see everything without exaggeration, to stop strong desire and attachment. When we see something attractive, but understand its true nature, this does not stop us seeing the attractiveness but stops too strong an attachment to it. Attachment is always backed by ignorance. So if we have realized the true nature of something first, it makes a big difference to our way of dealing with it.

So when we encounter an attractive object it becomes for us like a rainbow in summer, it appears beautiful. It is relatively so, but we don’t see it as real. So the clinging to something real will not arise. If we slowly lose this grasping of the object as real, attachment to it from ignorance will not arise, “Whatever the kind of desire or hatred, it is accompanied by deluded ignorance.” And from Aryadeva’s Four Hundred Stanzas on the Middle Way, “Like the sense organs of the body, ignorance is enclosed within us, and all the delusions which exist can only be conquered by defeating ignorance.” Therefore, although an object appears beautiful, as we see that it is unreal, impermanent, and this destroys our attachment. This is a new way of abandoning attachment. Before we did so because it was impure, arousing attachment, now we do so because it is unreal. If we can practice both this has great effect.

The first way was temporary, suppressing, but not eradicating attachment. Seeing the false nature of the object of attachment, and if we can have a strong certainty about, and see clearly the true nature of the object, this will help greatly to stop attachment to it.

The twenty-fourth practice of the bodhisattva:

All sufferings are like the death of our son in a dream. To hold as real what is illusory is tiring. Therefore, when we meet an unpleasant circumstance to see it as illusory – this is the practice of the bodhisattva.

Hatred can arise from unpleasant circumstances or suffering. Therefore, if we see that such suffering lacks real existence, see it as though it was only illusion, this will help to stop hatred. Therefore to approach a circumstance in this way is a practice of the bodhisattva.

The twenty-fifth practice of the bodhisattva:

One who wishes to attain buddhahood has to sacrifice even his own body, which is the most precious and difficult object to sacrifice. Other external objects need also to be sacrificed. Giving (Skt: dana) is necessary, but without looking for reward or fruit, such as being born in a rich family in the future. Therefore to give charity solely for the benefit of others – this is the practice of the bodhisattva.

The twenty-sixth practice of the bodhisattva:

Someone who, without behaving morally, thinks he can help others is an object of fun, since without sila he cannot even bring about his own well- being. Therefore to keep moral standards without a samsaric wish or aim – this is the practice of the bodhisattva.

Even to achieve a better state of being in samsara depends fully on observance of sila, which is the main cause of rebirth in more fortunate realms. Without sila one cannot even for one’s own benefit attain a fortunate realm in samsara. And if we cannot even do this, it is humorous to think of helping others without moral conduct. The object of the latter is solely to benefit other sentient beings. If we do behave morally just to achieve a fortunate realm, this is practice of Dharma, but not of the bodhisattva. The precept is, “I must help sentient beings. Therefore, I must attain buddhahood to help them properly. Therefore I must pursue many practices. I must therefore attain a precious opportunity to fulfill these practices. Therefore to retain this precious human body for rebirth I practice moral conduct.” Then such conduct is pure, without a samsaric aim, in order to attain buddhahood.

Then there is patience or forbearance (ksanti):

The twenty-seventh practice of the bodhisattva:

To a Son of the Victorious One who wishes to have the wealth of merit, all harmful circumstances are the same as precious treasure; to practice patience without hatred towards anyone – this is the practice of the bodhisattva.

This is an essential practice because it helps trifling. Adverse circumstances are the same in this way. If someone who is more powerful than we are imposes his will on us then our forbearance is not the real thing, but when someone who is in many ways our inferior harms us then when we practice forbearance, even if we have the power to fight back or retaliate, this is the real kind. So to practice patience in all adverse circumstances is a practice of a bodhisattva.

Energy or the right effort (vīrya):

The twenty-eight practice of the bodhisattva:

When we see how much energy is expended by Sravakas and Pratyekabuddhas working to enlighten only themselves, then how much more perseverance must be practiced by those who wish to liberate all sentient beings – this is the practice of the bodhisattva.

The twenty-ninth practice of the bodhisattva:

This is the union of higher insight (into the true nature of reality) and single-minded, one-pointed concentration. By knowing that it destroys delusion completely, we should practice dhyana (beyond the four samsaric dhyanas of formless realms) – this is the practice of the bodhisattva.

We practice higher insight (or deep insight) in order to realize shunyata and thus cut the root of samsara. To combine it with one-pointed concentration in meditation.

Wisdom with method (prajna):

The thirtieth practice of the bodhisattva:

Without method, the other five perfections do not enable us to achieve fully accomplished buddhahood. Therefore to practice prajna with method, rejecting the pseudo-reality of the triad (the independent, permanent self-existence of the actor, the act, the acted upon) is necessary. Without prajna the practice of the other five perfections is like blindness. With prajna, like sight. Therefore it becomes a true cause of buddhahood. To attain this we must have the union of prajna and method. What is the nature of prajna? Seeing the triad – this is the practice of the bodhisattva.

The thirty-first practice of the bodhisattva:

Other practices are required. If we don’t have self awareness, mindfulness, we won’t evaluate our own shortcomings. If we don’t do this it is possible to do something contrary to Dharma in the guise of a Dharma practitioner. Therefore we should constantly evaluate, judge our own faults, and abandon them. We must be constantly mindful and watchful of our motives and actions. We must watch our speech and mind. When we see that something is going wrong, correct it immediately – this is the practice of the bodhisattva.

The thirty-second practice of the bodhisattva:

Next there is the question of finding fault with, and criticizing others. If from delusion we criticize the faults of bodhisattvas, we harm ourselves. If they have entered Mahayana, it is wrong to criticize others’ faults, we should only speak of our own – this is the practice of the bodhisattva.

To speak about others’ faults is very dangerous. What we must look for are our own faults in body, speech and mind, not the flaws of others. In order to help others we can point out their faults or mistakes. But if we criticize others, publicize their faults, find fault, while concealing our own faults, this is not a practice of the bodhisattva. If we do criticize others this is generally bad, and especially wrong if the other person happens to be a bodhisattva.

As the First Dalai Lama says, “We must keep in mind the kindness of sentient beings in general, and especially train ourselves in the right view of those who practice Dharma, and defeat delusion, the enemy within.” Our duty then is to think of the kindness of others, to have a good opinion, a pure view, and give them the benefit of the doubt. This is especially true for those who criticize followers of Dharma, taking sectarian views of “them” and “us.”

All the great gurus who have founded the different traditions had good reasons, were fulfilling the prophecies of Buddha and his word, and wished for the enlightenment of all sentient beings. We should bear this in mind and not act from delusions, which means criticizing, rejecting and then becoming aggressive. If one acts like this it is a very bad and unskillful deed in relation to Dharma.

There is a very precious story about the First Dalai Lama. He was very old and one day he told his disciples that he was very disheartened. “What are you worrying about?” they said, “it is prophesied that you will be reborn in Tushita.” He looked sadder still and said, “But that’s the trouble, I want to be reborn in a worldly existence in order to go on helping others.” These are true words of a bodhisattva. These phrases have a great meaning for us, they are the essence of Mahayana Dharma. So remember the kindness of sentient beings, don’t criticize Dharma followers; train your mind to take pure views.

The thirty-third practice of the bodhisattva:

Domestic quarrels about respect or things we feel are due to us interfere with our practice of learning, contemplation, and meditation, so to abandon home and friends, the house of patrons – this is the practice of the bodhisattva.

Even very great gurus, because of these worldly matters, have obtained a bad reputation in this way. An example is Jamica Shepa, whose close relation with a king whose queen killed another great guru got him criticized, however, unjustly, for not intervening in time.

All such involvements in worldly matters, offerings, status, surroundings, can give rise to different kinds of trouble. And one’s practice of Dharma deteriorates in the process. Too many worldly friends, patrons, possessions can produce bad consequences. As the Bodhicaryavatara says, “Live everything at an ordinary level, without too much attachment or clinging, unduly strong ties or relationships.” Therefore to abandon attachment to worldly matters is a practice of a bodhisattva.

The thirty-fourth practice of the bodhisattva:

Harsh speech will disturb others’ minds and cause the practice of those who wish to be bodhisattvas to decline. So to abandon harsh speech, which is disagreeable to others – this is the practice of the bodhisattva.

Hard words can easily arise in our life, but they are harmful to others and therefore very much not the practice of a bodhisattva. If one gets into the habit of using harsh speech it is difficult to stop, so those who have a quick temper must watch themselves. Whenever delusion arises, strike it down straight away, this is the practice of a bodhisattva.

The thirty-fifth practice of the bodhisattva:

Therefore we should never get into the habit of delusion. Extinguish the smallest flames, stop the floodwaters at their source, from their very beginning. There are times when we must use awareness as a sentinel, holding the weapons of antidote against hatred, desire, and jealousy, and strike them down from the outset – this is the practice of the bodhisattva.

As is said in the Eight Verses on the Training the Mind, “In all actions may I watch my mind and whenever delusion arises, by knowing it destroys me and others, may I extinguish it from the very beginning!”

The thirty-sixth practice of the bodhisattva:

In short, whatever we do, to be someone who is mindful and aware of the state of his mind, and to practice this for the welfare of others – this is the practice of the bodhisattva.

So in all circumstances we must be mindful, so that nothing in us is secret, everything is known. Therefore by paying attention whenever action in speech, mind or body arises which is harmful to us and particularly to others, we must think, “I am a follower of the bodhisattva path, of Mahayana Dharma, born in the Land of Snows, where the union of paramitas and tantras has flourished. But I am also supposed to have a faith and will to follow Mahayana, and have the opportunity to be guided by many precious gurus, and the good fortune to hear their instructions. With all these opportunities, if I still have the will to act badly this is deceiving the gurus and bodhisattvas, which would be absolutely wrong and evil for myself.” We should therefore be particularly careful to safeguard ourselves against these bad actions by constant mindfulness and awareness. As Shantideva says, “I beseech you with clasped hands to be mindful in all your activities.” Therefore, with such a character we must practice for the benefit of others, dedicate all our qualities, happiness, abilities of body, speech and mind to the service of sentient beings. We should constantly be nothing more than a servant of other sentient beings, and have nothing else to do than work for their benefit.

The thirty-seventh practice of the bodhisattva:

All the merits we’ve accumulated by effort should be dedicated to eliminating the suffering of mother sentient beings by the wisdom of seeing the “purity of the triad” (that dedicator, what is dedicated, and dedicatee lack real existence) – this is the practice of the bodhisattva.

The merit we accumulate from these practices should then not be dedicated to our own well-being, freedom from samsara, existence in higher realms and so on, but solely to the attainment of buddhahood in order to relieve the suffering of others. We must also have the wisdom to see the void of the existence of the triad. This constitutes the 37th practice.

So the main part is now finished. By following the teaching of sutras, tantras and Sastras, by following the instructions of gurus, these thirty-seven practices have been written down for the benefit of those who wish to follow the path.

Because of my weak knowledge and little learning, there is no fine language here to delight the erudite. But being based on the teaching of the sutras and gurus I think they are free from flaws and therefore practices of a bodhisattva. My innate wisdom, like my learning, is also weak, so it cannot please those with great ability. But because it is based on the sutras, tantras and Sastras, and gurus’ instructions, I think these practices are true ones.

Then our author confesses:

But because the actual practices of the bodhisattvas are deep and vast, like great waves they cannot be fathomed completely by one as ignorant as I, so I must ask gurus to show forbearance for any contradictions, inconsistencies, and repetitions, and to forgive my mistakes.

Then comes his dedication:

By the merit I have obtained from this work, may all sentient beings, by the power relative and absolute bodhicitta, without remaining in the extremes of samsara and nirvana, obtain full buddhahood like Avalokiteshvara.

Thus he dedicates all the power of merit of his composition to all sentient beings so that they achieve relative composition to all sentient beings so that they achieve relative and absolute bodhicitta. By absolute bodhicitta, freed from samsara, by relative bodhicitta from nirvana, so by freedom from the two extremes may they obtain full buddhahood.

Thus it was composed by the Venerable Togme Sangpo for the benefit of himself and others in the cave of Rinchhen Pouk (Precious Cave) at Ngwiltrichou.

Notes

1 This verse was not discernable in the transcript. The translation given is from Transforming Adversity into Joy and Courage, Geshe Jampa Tegchok, 1999, Snow Lion Publications, Ithaca, NY.

A translation by Acaarya Nyima Tsering was published in Dharamsala by the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, 1995. A copy of this publication can be obtained here.