His Holiness the Dalai Lama: Aryadeva points out to first understand the Buddha’s teaching on emptiness, Buddha’s teaching on no-self.

3. Day Two, Morning Session, July 11, 2008, Part one. Using Human Intelligence to Transform Our Minds. Perfection of Wisdom. Goals and Conditions for Learning. How to Guide Students. Understanding Emptiness as the Key. Chanting of Heart Sutra in Vietnamese.

Using Human Intelligence to Transform Our Minds

His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Now, I think in the beginning of the afternoon session, perhaps some questions may be useful.

So, Buddhadharma. Some scholars described, “Buddhism is not a religion but a science of mind.” I think it’s quite true, because in Buddhism, like any other non-theistic religion, the basic concept is law of causality—cause-and-effect, cause-and-effect, goes like that.

So the thing which we are very much concerned with, that is suffering, pain, and the joyful or pleasant, happy…

Thupten Jinpa: …happiness.

His Holiness: So the pains and pleasures, these things are feelings. So feelings means: part of our mind. So the causes of that (of course external factors are also there) but mainly within our own mind. So logically, in order to reduce suffering, pains, worry, sadness, fear: they ultimately depend upon our mental attitude.

So shaping in new ways our mind, just mere determination, or mere wish, to some extent it has some effect, but that cannot sort of affect us in a more profound way. So here I think conviction, firm conviction, that is something important.

Now firm conviction must come out of analytical meditation. So therefore the Buddhist way of approach is—utilize human intelligence in maximum way, and through that way, transform our mind.

So now in Buddhadharma—the essence of all Buddhist teachings—based on the four noble truths. [continues in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So when we speak of the four noble truths we recognize two sets of cause and effect. [pause for adjusting of microphones]

So when we speak of the four noble truths, essentially, within the teaching of the four noble truths we recognize two sets of cause-and-effect: one set that relates to the nature of suffering which we do not naturally desire. And also that suffering and its origin relate to one set that pertains to the afflicted class of phenomena or unenlightened existence. And a second set of cause-and-effect we find in the teaching of the four noble truths relates to happiness—what we aspire for and what we wish to achieve—and that cause-and-effect category belongs to the class of enlightened phenomena or enlightened class.

Perfection of Wisdom

His Holiness: And then Sanskrit tradition…[continues in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So in the case of… We were talking about the importance of determination but at the same time, aspiration and determination in itself cannot bring about the profound transformation we are seeking for. So, for example, at the beginning of the Heart Sutra which was chanted, the Heart Sutra opens with a dialogue between Shariputra and Avalokiteshvara while the Buddha Shakyamuni remained in the meditative state.

So in the opening of the dialogue between Shariputra and Avalokiteshvara a question is raised: “For a bodhisattva who wished to engage in the practices of the perfection of wisdom, how shall he or she go about doing it?” And then the text opens with a saying that… the statement that, “The bodhisattva who wishes to engage in the practices of the perfection of wisdom must proceed in the following manner. He or she must view all the five aggregates—the physical and the mental aggregates—to be devoid of inherent existence.” So right there, at the beginning, at the very opening of the text itself, there is a reference to the need for cultivation of the wisdom of emptiness.

So the point being made here is that, although determination based on aspiration is very important to motivate one toward the practices, but it is the determination and aspiration complemented with the faculty of wisdom that is going to make the big difference. So between the two primary modalities of an approach on the path—one approaching more in the form of aspiration and determination, one through the application of intelligence— between these two, it’s the application of the faculty of intelligence that is more important.

So when we speak about wisdom here, generally in the text, there are mentions of wisdom pertaining to the conventional level of truth of phenomena and wisdom pertaining to the ultimate level of truth of phenomena. Between these two, it is the wisdom related to the understanding of the ultimate truth that is primary. And so when we speak about perfection of wisdom, for example, even the very title of the text is referred to as Perfection of Wisdom. So here we are talking about not just any wisdom, but a wisdom realizing emptiness, and that also at the level of a perfection.

So when we speak of the perfection of wisdom, we are talking about the realization of emptiness which is reinforced and complemented with a factor of awakening mind, of bodhichitta. So the direct realization of… The wisdom that directly realizes emptiness that is complemented with the factor of bodhichitta—that is referred to as the perfection of wisdom.

So when we look at the etymology of the term perfection of wisdom, prajna-paramita, or paramita, paramitameans to go beyond. So, in the etymology, one can understand this in terms of the actual process—that which goes beyond or that to which one has gone beyond. So if you understand perfection in terms of the actual process, then the wisdom directly realizing emptiness that is present in the bodhisattva’s mental continuum, that can be understood as the perfection of wisdom. So the main point is that all of this emphasizes the role of wisdom, particularly in the Sanskrit tradition.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So for example just now we had the recitation of the Heart Sutra, and towards the end of theHeart Sutra there is a mantra, a string of mantra, which begins in the following, which reads in the following way—tadhyata gate gate paragate parasamgate. So tadhyata means ‘it is thus’, gone, gone, gone beyond. So this explains the process of going beyond.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So of course the major explanations will come later.

His Holiness: So that’s the basic sort of structure of Buddhadharma. Now…

Goals and Conditions for Learning

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So the next major outline of the text we will be reading from or addressing is: having explained the greatness of the author and the teaching itself, the third outline is how to now engage, proceed with, the exposition, teaching and listening to the teaching itself and with what kind of attitudes and states of mind.

And here the main point being made is that the reason why we engage in the exposition of and listening to the teachings is to really fulfill our aspiration to bring about the realization of our immediate and long-term welfare. And in order to bring about the realization of that aspiration successfully, certain conditions need to be met on the part of both the listener and on the part of the teacher, so that whatever is taught and whatever is heard really serves the purpose of becoming as beneficial and as effective as possible.

So on the part of the listener certain conditions need to be created so that your state of mind and your attitude and your motivation for listening to the teachings remain pure so that it makes you receptive to benefit from the teachings. And on the part of the teacher also, it is important to make sure that, as far as the motivation of the teacher giving the teachings is concerned, it is unadulterated, it is pure. So the motivation is really to bring benefit to the student, to the listener.

And here, for example, the qualities that are very important are… for example in the qualities that are listed for attracting students and gathering students, there are four qualities that are identified. And the last two are very important. These two are teaching appropriately and living those ideals that you teach, living through your own example.

So these are very important on the part of the teacher so that whatever is taught… And also, as much as possible on the part of the teacher, it is important to have the skills to adapt the teachings according to the level and the need and specific circumstances of the listener, so that whatever is presented is most effective in bringing about the necessary transformation that one is seeking.

So once these conditions are created, then when you engage in, participate in, listening to a teaching or giving a teaching, then the activity will become beneficial. So these are the points Tsongkhapa is making under this outline.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So the fourth major outline is, “How to lead the students with the actual instructions.”

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So in this context when we talk about instructions, we are talking about instructions of the Buddha, Buddha Shakyamuni.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So with regard to the procedure by which students are led on the basis of instructions, there can be different approaches. For example, even in Nagarjuna’s own writing we see a divergence of approaches. For example, in his Precious Garland, the main procedure that is adopted is first by presenting all the teachings that are related to the realization of attainment of a fortunate rebirth, higher rebirth in a fortunate realm. So within that context, the teaching on the morality of abstaining from ten negative actions and also how to maintain a way of life that is free from falling prey to various forms of wrong livelihood—all of these are explained within the context of a practitioner who aspires to attain a favorable rebirth in a higher realm in the next life.

And then, having explained that part of the practices, then in the second part, in the latter part of the textRatnavali (Precious Garland) Nagarjuna then goes on to explain all the practices that are related to the attainment of liberation, nirvana and definite goodness. Here in this context, the presentation of the view of emptiness is explained—the correct view of emptiness is explained.

So now this approach, since Ratnavali (the Precious Garland) is explicitly written as a letter of instructions, a letter of advice to a king, so the approach being presented in that is very specific to a particular individual. Whereas if you compare that to Nagarjuna’s own text, Commentary on the Awakening Mind (Bodhicittavivarana) then the approach is very different.

In the Commentary on the Awakening Mind in fact, the entire text is an exposition of a verse, a stanza, from the root tantra of Guyasamaja, where it explains how all phenomena are devoid of intrinsic existence and also devoid of the duality of subject and object, and it explains equanimity in terms of the absence of inherent existence of all phenomena. So that passage from Guyasamaja root tantra forms the basis for the exposition of this particular text by Nagarjuna which is a commentary on the awakening mind. And in this text, since it is a commentary on exposition of this particular stanza from the Guyasamaja Tantra, clearly the audience that is being targeted in this text are really practitioners of advanced capacity because they are practitioners of highest yoga tantra. Therefore for trainees of highest yoga tantra, the procedure of the path presented there is very different.

So in fact, in this text Nagarjuna immediately begins with an explanation of emptiness. So there the practices that are related to cultivating the correct view of emptiness are presented first. So on the basis of studying the teachings on emptiness, when one develops a deep understanding, and on that basis when one reflects critically upon one’s understanding, then on that basis one will develop a deep ascertainment of the meaning of emptiness. Which, when through meditative practices becomes internalized, then the individual practitioner will even arrive at a point where there will be a certain experiential flavor to the person’s understanding of emptiness.

And once you have that kind of understanding of emptiness, then you begin to recognize the possibility of an end to suffering because you recognize suffering arising from ignorance which is a distorted state of mind. And you come to recognize that this distorted state of mind has an antidote—a powerful antidote— that directly negates the content of that perspective, of that ignorance. And by seeing that for the root of suffering there is a powerful antidote that can eliminate it, you begin to recognize the possibility of an end to suffering.

And so once you recognize the possibility of an end to suffering, then this realization of the possibility of an end to suffering can in fact generate within you a powerful feeling of compassion for all beings. So therefore Nagarjuna in fact writes in the Bodhicittavivarana (the Awakening Mind) where, having explained the meaning of emptiness, at one point he says, “In the person in whom the realization of emptiness has arisen there is no doubt that attachment for all beings will arise.” Now here “attachment” refers to compassion.

So what we find in the Bodhicittavivarana is a procedure where the practitioner begins with cultivating the understanding of emptiness, and thereby cultivating the ultimate awakening mind, and then on the basis of that ultimate awakening mind, one cultivates the conventional awakening mind which is bodhichitta, and proceeds in that manner.

So these two approaches are very different. And so, if you look at these two approaches, then it makes sense. For example a kind of a latter-day Tibetan master Nyen-tsun Sung-rab developed the phrase where he talks about certain approaches of the teaching which are specific to an individual and certain approaches of the teaching which are taking into account the overall structure of the path. So you can see that this kind of understanding really applies to the two quite different approaches found in Nagarjuna’s teaching, one in the Precious Garlandand the other in the Commentary on the Awakening Mind.

So, in short, when Tsongkhapa talks about how to guide the student on the basis of instructions, here instructions refer to the Buddha’s instructions. And the purpose of the Buddha’s instructions is to bring about the attainment of definite goodness, which is the liberation and buddhahood, and there the principal factor is really the cultivation of wisdom as explained before.

Understanding Emptiness as the Key

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So with respect to these two diverse approaches of presenting the Dharma—one with relation to a specific individual’s need and context, one from the point of view of the overall presentation of the Buddhadharma—here, for example, in the 400 Stanzas by Aryadeva, again Aryadeva talks about these two different primary purposes of the Buddha’s teachings: one aimed at realization of an immediate aspiration, which is the attainment of a favorable rebirth; the other one is attainment of definite goodness or liberation.

Here if you look at the teachings, the practices, that are related to the attainment of a favorable rebirth, then we are primarily talking about understanding the law of causality and the teaching on dependent origination in terms of karma, the law of causality. And there the primary law of causality that we are trying to understand is really karma.

And, however, when it comes to the presentation of karma and the karmic laws, there are many aspects, facets, of the karmic law that remain totally obscure to us. And similarly if you look at the various presentations of the subtleties of various aspects of the various levels of realization of the path, at this point many of these very subtle aspects of the various levels of the path will remain obscure to us. So in these cases, the way in which we cultivate conviction in these aspects of cause-and-effect initially will primarily take the form of having some kind of admiration, and having some kind of conviction based upon that admiration.

However Aryadeva points out that, in terms of cultivating a conviction in those aspects of the Buddha’s teaching, the most skillful way of doing this is to first understand the Buddha’s teaching on emptiness, Buddha’s teaching on no-self. And so he says that with relation to the Buddha’s teaching related to very obscure facts, one can approach them and cultivate conviction in them on the basis of having a deep conviction in the Buddha’s teaching on emptiness.

Similarly Dharmakirti says in his Pramanavartika (Exposition on Valid Cognition) that because the Buddha, the teacher, has proven to be faultless or reliable with respect to the teachings on the principal teachings—particularly on the four noble truths, no-self and emptiness—therefore one can extend the same level of conviction and confidence in other teachings that the Buddha has given.

So what we see here is that, when it comes to the presentation of the Buddhist path from an overall point of view, the principal approach is to really proceed with cultivating a deeper understanding of the principal teachings of the Buddha which relate to the four noble truths and which relate to the teachings on no-self and emptiness. And so even in the context of the four noble truths, the key point is to really develop a deeper understanding of the third noble truth, which is the truth of cessation, and to recognize and appreciate the possibility of the attainment of cessation.

Otherwise, if we look at the teachings on suffering and its origin and then, if there is no possibility of an end to suffering, then there is simply no point in reflecting on, contemplating deeply on, the nature of suffering. Because if there is no possibility of an end to suffering and there is no possibility of the attainment of cessation of suffering, then any kind of deeper contemplation on suffering and its origin will result in depression. And clearly Buddha was not interested purely in making his followers depressed by delving ever more into the nature of suffering.

So for example, when we look at the nature of suffering, we are talking about evident suffering that we can all identify. Also we are talking about the suffering of change that we conventionally identify as pleasurable experiences. Then there is the third level of suffering which is the suffering of conditioning. So, as one contemplates deeply upon the nature of suffering, one comes to recognize that particularly the suffering of conditioning, which is the most profound level of suffering, arises on the basis of karma and afflictions which are all rooted in the fundamental ignorance and grasping at some form of enduring self.

And then once one recognizes the distorted nature of that grasping, then one will appreciate the possibility of cultivating a perspective that directly opposes that. And through understanding this, one will recognize that there is at least a possibility of bringing an end to that suffering.

And once you recognize that, then there is a real meaning and purpose to contemplating on suffering. So that’s the reason why there is a degree of confidence behind the Buddha’s teaching on suffering and its origin, because the confidence is stemming from the fact that he knows there is the truth of cessation.

And so when we understand the Buddha’s teaching, we need to relate all the teachings to the principal teaching on emptiness, and the purpose of that is the attainment of liberation. Because otherwise, if we confine our understanding of the Buddhadharma specifically to individual practices alone (say for example, guru yoga or proper reliance on the spiritual teacher, or cultivation of the awareness of death and impermanence, or taking refuge in the three jewels, and living one’s life according to following the precepts…

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: Sorry… taking refuge in one’s own object of refuge and following the precepts based upon that, going for refuge, all of these teachings, practices, can be found in non-Buddhist teachings as well. Not only in the classical historical non-Buddhist teachings but even in all the contemporary non-Buddhist spiritual traditions, you can find a version of all these—a version of taking refuge, a version of living one’s life according to the precepts stemming out of that taking refuge, some recognition of the importance of awareness of death—all of these can be found in the non-Buddhist traditions as well.

And similarly, for example, when we look at the practice of morality, say for example, abstaining from killing, the act of abstaining from killing need not be by itself a Buddhist practice. One can be totally nonreligious and out of fear of legal consequences abstain from killing. And that is the act, but that is not a spiritual religious practice. Similarly, a non-Buddhist practitioner can adopt the morality of abstaining from killing with a view or the belief that doing so would violate God’s wishes.

So again, you can see that by themselves these individual practices, so long as you don’t tie them to the ultimate aim of the Buddhist path and point of the Buddha’s teachings, they in themselves are not specifically Buddhist practices. They are common practices that are found in all the other traditions.

For example within the morality of abstaining from the ten negative actions, we have three mental: abstaining from covetousness, ill will or harmful intent, and wrong view. So we can see that this is at the level of the practices relevant to the person of initial capacity. So there, attachment and aversion and ignorance are not listed, but very specific forms of these three poisons are listed. Instead of the general attachment, a more specific form, covetousness, is listed. Instead of aversion in its general category, a more specific form, harmful intention, is listed.

And also with wrong view, at the level of the initial capacity practice, wrong view need not necessarily be understood in terms of the law of karma and so on. But rather wrong view can be understood in terms of a person who defies the morality and engages in, say for example taking life, thinking that there are going to be no moral consequences for this. So that kind of view is a wrong view. So you can see all of these practices can be, in themselves, not necessarily specifically Buddhist.

However, what distinguishes a particular spiritual practice as Buddhist is when it is tied to the overall motivation and purpose of the attainment of liberation, which is based upon recognition of the possibility of an end to suffering and its origin—which is based upon the recognition of the possibility of the truth of cessation—and where all these practices are complemented with the understanding of the Buddha’s teaching on no-self and emptiness. Then these become Buddhist practices.

And even in the case of liberation, one needs to understand that the way in which Buddhism defines moksha, or nirvana, is not really transcending into some form of physical plane that is a heavenly realm. Rather moksha or liberation is defined in terms of a quality or a state of mind where the individual practitioner has reached a state where the person has purified his or her mind from the stains of grasping at the inherent existence or true existence. And therefore the point is that the teaching on no-self and cultivation of the view of no-self really becomes central to defining any spiritual practice as being Buddhist. And so the teaching on no-self and the cultivation of the view of no-self is what defines a spiritual practice as Buddhist.

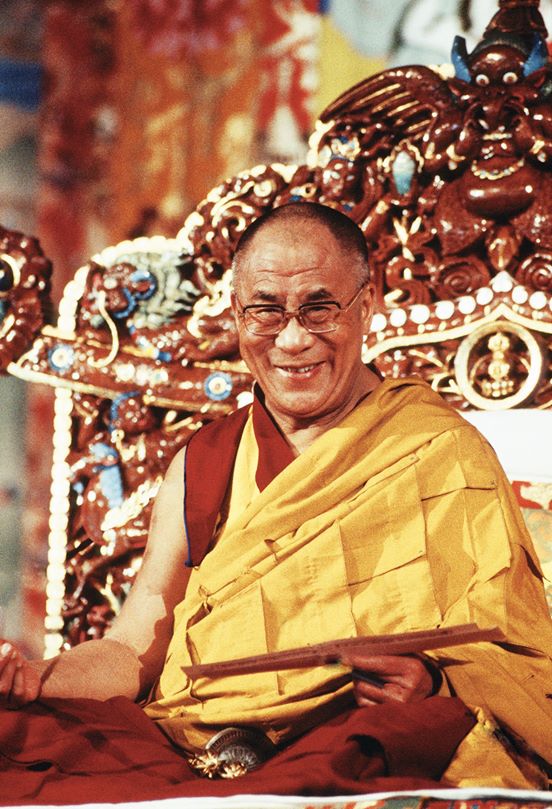

In July 2008, His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama gave a historic six-day teaching on The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment (Lam-rim Chen-mo), Tsongkhapa’s classic text on the stages of spiritual evolution. Translator for His Holiness was Thupten Jinpa, Ph.D.

This event at Lehigh University, Pennsylvania, marked the culmination of a 12-year effort by the Tibetan Buddhist Learning Center (TBLC), New Jersey, to translate the Great Treatise into English.

These transcripts were kindly provided to LYWA by the Tibetan Buddhist Learning Center, which holds the copyright. The audio files are available from the Tibetan Buddhist Learning Center’s Resources and Linkspage.

The transcripts have been published in a wonderful book, From Here to Enlightenment, edited by Guy Newland and published by Shambhala Publications. We encourage you to buy the book from your local Dharma center, bookstore, or directly from Shambhala. It is available in both hardcover and as an ebook from Amazon, Apple, B&N, Google, and Kobo. http://www.lamayeshe.com/article/chapter/day-one-afternoon-session-july-10-2008