His Holiness the Dalai Lama: Within the mind, all the mental states are by their very nature subject to change.

5. Day Two, Afternoon Session, July 11, 2008. Part one. Qualities of the Teacher. Relying on the Spiritual Teacher. The Process and Meaning of Meditation. Analyzing Afflictions and Their Antidotes.

Questions for the Dalai Lama

His Holiness the Dalai Lama: Sorry. 15 minutes late. Oh, some questions, yes.

Thupten Jinpa: [The questions below in quotation marks are from members of the audience.]

“Your Holiness, how is it possible to go about living an everyday life working at a job, paying bills, taking care of family and so on, but without grasping?”

His Holiness: Without grasping…[continues in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So the question is how do you understand the idea of grasping here? So for example, in relation to others, if in your engagement with others, if the engagement is tainted by forms of grasping such as strong attachment, craving, or aversion, anger and so on, then that form of grasping is undesirable.

But on the other hand, when you’re interacting with other sentient beings, with awareness of that other person’s needs or suffering or pain, then you need to fully engage with that other person’s pain and be compassionate and be engaged with that. So there is some form of attachment, some form of engagement.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So in fact Buddhist masters have used the term, the very word “attachment,” in describing the quality of compassion for others. For example, in the salutation verse of Haribadhra’s Commentary on the Perfection of Wisdom text, there he talks about compassion that is attached to other sentient beings. And, similarly, I cited Nagarjuna’s text where Nagarjuna says that in the person in whom the realization of emptiness has arisen, then attachment for other sentient beings will spontaneously arise.

“How do you define true happiness?”

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So in the context of the four noble truths, when we are talking about suffering and happiness, then the notion of happiness is also not just from a positive characterization of the state, but also negatively characterized as a state that is free from suffering and its causes. So we are talking about a notion of happiness that is more lasting, so it’s a lasting happiness.

His Holiness: Then generally perhaps, happiness… usually I sort of consider happiness means deep satisfaction. So, for example, some physical hardships or some suffering can bring satisfaction. So such things in that category still something is positive. So then satisfaction on the level of physical satisfaction and mental satisfaction. Now here mainly mental level satisfaction. So as I mentioned earlier, physical suffering, physical hardship, can bring mental satisfaction. So in this sense, in this context, happiness is more mental level satisfaction.

Thupten Jinpa: “Your Holiness, would you please explain…”

His Holiness: Perhaps, furthermore, mental level satisfaction with help of awareness, then good. Sometimes, out of ignorance, some mental satisfaction also is possible. Isn’t it? It’s very temporary. Shortsighted.

Thupten Jinpa: “Your Holiness, would you please explain the method and the uses of analytic meditation?”

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: “Would you please explain the method of how to use analytic meditation?” Analytic meditation.

His Holiness: Analytical? [continues in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: This topic will come later.

“If suffering is caused by mind, what is one to do when facing environmentally difficult situations externally that are hard to change? For example, if a spouse or father is an alcoholic, should the partner or the child stay and seek happiness, despite the partner’s drinking, or take the children and seek life without the drinker?”

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: The line here, the suffering being “caused by the mind,” is too general because even in the Buddha we accept the presence of mind. So the cause of suffering is not just the mind itself but it’s an undisciplined, untamed mind.

His Holiness: [discussion in Tibetan with Thupten Jinpa]

Thupten Jinpa: Of course here it depends upon how you define what you mean by happiness here.

His Holiness: In general sense, of course I think there are external conditions, external sort of causes, factors… [continues in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So, generally speaking, there are, of course, conditions that are external and some conditions that are internal.

His Holiness: …and so sometimes…

Thupten Jinpa: …so then, of course, one has to think what’s the best course of action?

“If there is no inherent self, what part of the mind transmigrates?”

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: This will come later.

“How do you overcome the sadness and anger from a difficult childhood?”

His Holiness: [in Tibetan then English] I think generally I think of the sixth…[continues in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So we will discuss that in the context of the discussion of the perfection

of forbearance.

“Your Holiness, you said that we relate to events based on our perceptions, not on what is reality—that we need to differentiate between our perception and the reality. How will we know the reality and not be influenced by our perceptions?”1

His Holiness: This morning when I used the words the ‘reality’ and ‘appearance’ that’s within the context of two truths. But generally, I think one event, one thing, if you look from one angle you cannot see the full picture. One event, in order to know that, you have to look from various different angles.

Even a physical thing, from one dimension you cannot see the full picture. With three dimensions, or four dimensions, or six dimensions—then you get a clearer picture about the reality.

So, in order to know the reality, you have to look from various angles and from various dimensions. Otherwise when you see from one dimension it appears to be something, but there are always possible gaps between appearance and reality. Like that. So therefore investigation is very, very essential. So through investigation the gap between appearance and reality can be reduced. Only through investigation. [continues in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So earlier when I was talking about the gap between perception and reality, it was within the context of the teaching of the two truths…

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: …because we were discussing this in the context of trying to understand what lies at the root of our suffering, particularly the root of the afflictions, which is the grasping at true existence of things. And once you recognize that this grasping, this ignorance grasping at the true existence of things, engages with the events of the world primarily on the level of perception, on the level of appearances, and then grasps onto it, one comes to recognize that this does not accord with the actual reality, and one will be able to then gradually undermine the grip of that grasping. So that’s what we were talking about.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So now we will read from the text.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So we were talking about the qualities that are relevant on the part of the teacher, and particularly the teacher who is going to give instructions to the students on the basis of the actual instructions of the Buddha, all of which are aimed at bringing about the realization of our temporary, immediate aim of gaining fortunate rebirth into higher realms, and the long-term and ultimate aim of attainment of liberation.

And since this is the teaching, the person who is imparting the instruction needs to possess the qualities that are necessary for imparting such actual instructions because the quality and the effectiveness of the teaching would, to a large extent, depend upon the quality of the teacher. For example, when we choose a school, to a large extent the quality of the school is really determined by the quality of the professors and the teachers who are working in that university or school.

Similarly here, the effectiveness of the teaching to some extent is going to be determined by the quality of the teacher. So, generally speaking, the Buddha has outlined in various texts the kind of qualities that are necessary to the specific level of instructions, whether it is the master of a Vinaya practice or whether it is the master of a Vajrayana teaching, Highest Yoga Tantra. In all these cases there are specific qualities that are mentioned by the Buddha.

And here in the lam-rim context, the teacher that we are looking for is someone who is able to impart instructions that would encompass the practices of all the three persons of all the three levels of capacities. The key qualities that are mentioned are the ten qualities that are listed in Maitreya’s Ornament of Mahayana Sutras.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So in Tsongkhapa’s text (which is on page 71 of volume one) having cited a particular stanza from Maitreya’s Ornament of Mahayana Sutras, then Tsongkhapa writes the following. He says that:

“It is said that those who have not disciplined themselves have no basis for disciplining others. Therefore gurus who intend to discipline others’ minds must first have disciplined their own. How should they have been disciplined? It is not helpful for them to have done just any practice, and then have the result designated as a good quality of knowledge. They need a way to discipline the mind that accords with the general teachings of the Conqueror. The three precious trainings are definitely such a way.”

So this is quite a powerful statement that Tsongkhapa is saying, that the way in which the master should have disciplined his or her own mind is according to the teachings of the three higher trainings.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So since the instruction…

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So since the instructions that we are talking about, by which the students are being led, are instructions primarily related to the attainment of liberation, and since the principal practices that constitute the path to liberation are really the practices of the three higher trainings, so therefore on the part of the teacher who is giving such instructions, he or she must himself or herself embody the knowledge of the three higher trainings.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: And since the teacher is imparting an instruction that is not just for attainment of liberation but also attainment of full enlightenment of buddhahood, therefore one needs to present a path that encompasses the practices of bodhicitta, great compassion and so on. Therefore the qualities relevant on the part of the teacher include also having compassion and awakening mind.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So one of the qualities listed in Maitreya’s text is realization of suchness or realization of ultimate truth, and this partly reflects a kind of a philosophical view of the author, because the presentation is according to the Mind Only School, where a distinction is drawn between selflessness of persons and ultimate reality. So the wisdom in the context of the three higher trainings is identified with wisdom of no-self and the additional quality, realization of suchness, refers to the Mind Only School’s understanding of realization of selflessness of phenomena.

Qualities Needed by the Student

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So, when identifying the qualities relevant on the part of the student, Tsongkhapa identifies the three main qualities: being objective, endowed with the faculty of intelligence, and having interest.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So when searching for understanding the nature of reality, objectivity of standpoint is very important. The objective stance is very important because otherwise one will be swayed by one’s own biases and wishes. So therefore it will come in the way of actually understanding the actual reality.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So the second quality is being endowed with intelligence, and intelligence here refers to critical intelligence which has the ability to distinguish between what is right and what is wrong, what is correct in what is incorrect. And so the kind of intelligence we are talking about here is that of a critical, inquiring type.

This suggests that at the beginning one needs to have a form of skepticism, a kind of a doubt, because when you have doubt and skepticism, then this will lead to questioning. And when you go through questioning, then there is a real possibility of leading one to a deeper understanding of the fact. And therefore, on the other hand, if you approach right from the beginning with a single-pointed faith, then it wouldn’t open up questions. So having that skepticism and a critical intelligence becomes very important.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So because of this, if you look at many of the classical Indian texts, an emphasis has been made upon identifying what is the subject matter of a particular text, what is the purpose of gaining understanding of that subject matter, what is the long-term ultimate purpose of gaining such knowledge, and then what is the interrelation between these three factors.

The point here is that, because these texts are written for persons with a critical faculty, then a person with a critical faculty, when they engage with the text, they are going to first of all check what is the main subject matter of the text, what is the benefit and purpose and aim of gaining that knowledge, and what is the long-term final objective of the subject matter, and so on.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So, therefore, even in the texts, we have expressions that relate to the different ways in which people engage with the text. One is those of slightly inferior faculty approach the text primarily more from faith and devotion, and those of a kind of higher critical faculty of mind approach a text more from the point of view of understanding the reality that is presented.

Relying on the Spiritual Teacher

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: And then Tsongkhapa explains the actual process by which one relies upon the spiritual mentor on the level of one’s mind, what state of mind one should adopt, and also in actual practice, in physical action.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So we read from page 86, towards the end of the explanation of the process by which one must rely upon a spiritual mentor particularly through action, Tsongkhapa writes the following. (This is the third paragraph.) He raises the question,

“We must practice in accordance with the guru’s words. Then what if we rely on the gurus, and they lead us to an incorrect path or employ us in activities that are contrary to the three vows? Should we do what they say?”

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So then Tsongkhapa responds to this query that he raises, and he writes:

“With respect to this, Gunaprabha’s Sutra on the Discipline states, ‘If the abbot instructs you to do what is not in accord with the teachings, refuse.’ Also the Cloud of Jewels Sutra states, ‘With respect to virtue, act in accord with the gurus’ words, but do not act in accord with the gurus’ words with respect to nonvirtue.’ Therefore you must not listen to nonvirtuous instructions.” And then he writes, “The twelfth birth story…” (referring to the Jataka Tales) “…clearly gives us the meaning of not engaging in what is improper.”3

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So, to give an example: for example, with respect to master Atisha, among all the teachers, his principal teacher whom he considered to be the most important teacher, was Serlingpa. And Serlingpa was particularly revered by Atisha for his teachings on bodhicitta and the awakening mind. However Serlingpa’s own philosophical standpoint represented that of Mind Only school, so just because Serlingpa happened to be Atisha’s most important guru does not mean that Atisha would follow his guru’s instructions in every field. So Atisha, while being a devout student of Serlingpa, when it came to philosophical understanding of the Buddha’s teaching, he adopted the Madhyamika, the Middle Way school, rather than his teacher’s Mind Only standpoint.

The Process and Meaning of Meditation

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So then towards the end of this section, Tsongkhapa presents a summary of the manner in which one needs to relate to one’s spiritual mentor, and here he divides that section into two parts: the actual process itself and the refutation of misunderstanding or misconceptions.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So in the first section that deals with the actual process, Tsongkhapa explains it according to two parts. One is what needs to be done during the actual formal sitting meditation, and what activities one should engage in during the post-meditation periods. During the actual, formal sitting session, here, with respect to this proper reliance on the spiritual teacher, the main practices that are presented are primarily in the format of the seven-limbed practices and also six preparatory practices.

And then he explains what kind of activities one should engage in during the post-meditation periods as well, which would include maintaining a balanced habit with relation to one’s food, diet, and also learning to utilize even one’s sleep as a period towards enhancement of Dharma practice—and then guarding the gateway of the doors of the senses and living with a greater sense of awareness. So these are the main after-session practices.

And the point here is to engage in one’s Dharma practice in such a way so that both the formal sitting sessions and post-meditation sessions each can complement each other, so that the periods during the formal sitting sessions will enhance the virtuous activities during the post-meditation periods. And the practices and activities during the post-meditation periods will enhance the quality of your meditation during the formal sitting practices, so that each complement each other—so that you find a way in which the entire twenty-four hours of your day can be utilized towards the accumulation of merits and also enhancement of virtue.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So in the second outline, when he talks about refuting misunderstandings pertaining to meditation, the main point Tsongkhapa is making is the importance of analytic meditation.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So the Tibetan equivalent of the English term meditation is gom (bhavana in Sanskrit), and what this indicates or suggests is a form of deliberate cultivation and familiarization. Generally ‘goms pa is habituation or becoming familiar. But sgom pa is an active verb which indicates an agency who is deliberately involved in cultivating a particular form of familiarization.

His Holiness: [begins in Tibetan] …I think nobody from as soon as he wakes up in early morning (or early morning or late morning—I think some of you may be late morning when you get up) I think nobody at that moment expects, “Oh, today I should have more trouble. I should have more sort of fight. Or more anger.” I think nobody feels like that. Instead, from that moment, “Oh, today I wish for a very peaceful day, very leisurely day and happy day.” That way, I think.

Yet, you see many problems. So on this planet I think among six billion entire human beings, nobody wants trouble. But there is plenty of trouble. Most of this trouble essentially man-made trouble. Clear. So, one way, nobody wants trouble. At the same time there are a lot of man-made problems or trouble.

So the reason, the problem… the point is we want something good. But our mind is fully dominated by afflictive emotions. Afflicted emotions come out of ignorance, all levels of ignorance—ultimate ignorance and also some grosser levels of ignorance. Simply, we do not know the reality; we just look from one angle and then decide, “Oh, this is bad. This is good.” Like that.

So now here meditation means—try to control our mind. That means we should not let our mind be dominated by ignorance or by these afflicted emotions. So to just wish, “Oh, my mind should not be dominated by ignorance or afflicted emotions”—the emotion is very powerful. Destructive emotions are very, very powerful. They won’t listen to our wish. So the only thing is—we have to cultivate countermeasures for all these afflicted emotions. That’s the only way to reduce the afflicted emotions.

So in order for the development of the countermeasures, we cannot buy from a shop. Or those sophisticated machines, you see, cannot produce these things. So only through mental effort. Now—that is the meaning of meditation. Like that.

So the familiarization about these counter-forces, through that way, day by day, week by week, month by month, year by year, even sometimes life after life—the effort still continues life after life. Then gradually these counter-forces, because of habituation, you see, gradually increase and increase. The positive side increases, the negative side automatically is reduced, because these two things cannot remain together. It is contradictory. Like that. [continues in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So in this certain part of the text here, Tsongkhapa therefore makes the following point. He says that the problem with us is that we are dominated by our mind, and our course of actions and everything is dictated by our mind. However our mind is, in turn, dominated and dictated to by the afflictions, so it is under the power of the afflictions. And so because of this, although what we truly wish for is happiness, but we end up, you know, enduring suffering. And this is the reason why this is the case.

Analyzing Afflictions and Their Antidotes

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So when we compare our own states of mind, we will recognize that the undisciplined and untamed states of mind are those aspects of the mind that we are very familiar with. And because of long habituation over many lifetimes, they tend to be very powerful, and they are also quite spontaneous and natural when they arise. Therefore, when we cultivate the direct antidotes against them, in a sense we are learning new sets of skills. We are learning actually a new way of thinking—a new way of being.

Therefore initially, these antidotal forces are going to be very weak because we are learning something kind of quite new. But however over time, as we cultivate, our habituation will increase. And as our habituation to the antidotal forces becomes more and more strengthened, then their opposites, which are the undisciplined states of mind including the afflictions and the afflicted emotions, they will come to decrease in their force. And that’s the way in which the processes work.

And secondly, one thing that needs to be done is also to recognize that how, when we talk about afflictions, we are talking about a tremendously diverse phenomenon. And afflictions are in some sense very opportunistic. Wherever they find their ways, they can manifest themselves in many different ways. So we have to understand first of all, the various ways in which afflictions take their form and how they tend to appear to us.

For example, if we look at attachment and anger, then attachment we see as kind of a friend. Attachment is that quality of our mind which tends to attract others towards us, so it helps us bring together the conditions that we deem helpful for our survival.

Similarly anger and hatred tend to be those mental states that help us deal with obstacles that we don’t find desirable, and they are there to help us protect against these obstacles that we don’t want. So anger and hatred arise as almost like a kind of a trusted friend, there to protect us.

So we can see how, first of all, afflictions are so diverse and secondly, how there are ingenious ways in which afflictions can appear to us. And so therefore, in correspondence to the diversity of the afflictions, we also need to cultivate very rich, diverse antidotes as well, corresponding to them. Therefore, for example, Buddha, when he gave the Dharma, he taught eighty-four thousand heaps of teachings.

And similarly if you look at the commentarial literature that helps explain the Buddha’s teachings, for example, by Nagarjuna and his disciples and many other great Indian masters, there are so many extensive treatises. But the ultimate aim of all of these teachings, including the Buddha’s sutras, is really one—which is to help us deal with untamed states of mind and bring about its transformation.

Because the afflictions that disturb our mind are so diverse and they can manifest in so many different forms (and also they can manifest differently to different individuals) therefore, to suit the need of all the diverse practitioners and also to come up with the appropriate antidote against specific forms of afflictions, there are all these diverse teachings that we find.

And so, not only must we understand the afflictions themselves. Secondly, we have to understand their functions. Thirdly, we have to understand their causes, both internal and external conditions that give rise to these afflictions. And on that basis, we need to then cultivate these antidotes within us. Because even after simply recognizing the destructiveness of the afflictions, if we just simply make a wish that, “May they go away,” that approach is not going to be effective at all. So this simple recognition of their destructiveness is not adequate. We need to deliberately cultivate the antidotes within us.

Now how do we cultivate these antidotes within us? We do so through different levels of understanding: the level of understanding derived from learning; the level of understanding derived through critical reflection; and the level of understanding derived through meditative practice.

So the first level of understanding really arises on the basis of either listening to a teaching from a teacher or on the basis of oneself studying the text and so on. So you cultivate the intellectual understanding of the various characteristics of the afflictions and the appropriate antidotes and so on.

Then, on the basis of that understanding, you then need to critically reflect upon it repeatedly and deepen your understanding so that you arrive at a point where there is a genuine sense of conviction in their efficacy. So at that point you have arrived at the second level of understanding—the understanding derived through critical reflection.

And on these two levels, the analytic approach is the primary form of meditation. So the meditation takes particularly an analytic form on these two levels. And so, now when you are engaging in the critical reflection and using analytic methods, analytic meditation, then one needs to use also forms of reasoning taking into account particularly the four principles, which are the four avenues by which we engage with reality. So this is the principle of nature, the principle of dependence, the principle of function, and on the basis of these three principles, the principle of evidence.

So to give an example with relation to the nature of mind, we can say that the fact that mind is a phenomenon whose essential characteristic is that of knowing and luminosity— that is a principle of nature. Similarly, within the mind, all the mental states are by their very nature subject to change. They change on a moment-by-moment basis. They are transient. And that is again a principle of nature.

And furthermore in the mental domain, we also see there is a law of contradiction, opposing forces. For example, we know that hatred and anger towards someone is contradictory to loving-kindness and compassion towards that person. So these two opposing forces contradict each other. Similarly for example, even in the external world, we see opposing forces like heat and cold. They oppose each other so that they cannot coexist without one undermining the other. Similarly in the mental world you will have opposing forces, and the fact that there is this law of opposing forces is again part of nature, so that that belongs to the principle of nature. So you take these into account.

And then on the basis of that, then when you apply cause-and-effect relations, then you are using the principle of dependence.

And then, on the basis of recognizing these causal relations, then we will also come to understand specific functions of different mental states. Each of them has their own separate functions. Then here we are taking into account the principle of function.

And then on the basis of these three principles—nature, dependence, and function—then we can use logical evidence. Given this, such and such will follow. Given this, such and such will be the consequence. So on that basis, we will come to be able to apply the understanding of these principles and therefore apply the correct antidotes against the various aspects of the untamed mind—and bring about the knowledge.

So on the basis of this analytic meditation, when you then move on to the third level of understanding, there the primary approach will be more absorptive meditation where there is less analysis, but the primary approach is to maintain a single-pointed placement of mind upon the concluded fact.

And on that basis, as your single-pointed experience of that fact becomes more and more evident, then one will move finally to understanding derived from meditative practices. So in this way the transformation really takes place.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So what becomes clear is the role of the analytic meditation here. So when we talk about understanding developed on the basis of learning and critical reflection, one needs to use the faculty of intelligence.

Therefore the human form of existence is really a form of existence that is endowed, equipped, with the best faculty of intelligence. And therefore for a dharma practitioner, having the human existence becomes very important.

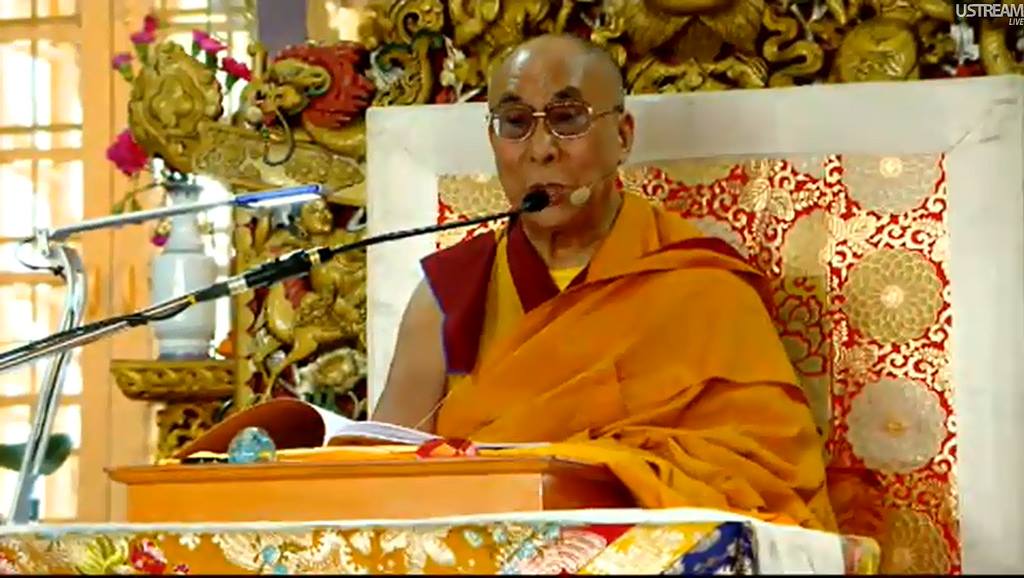

In July 2008, His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama gave a historic six-day teaching on The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment (Lam-rim Chen-mo), Tsongkhapa’s classic text on the stages of spiritual evolution. Translator for His Holiness was Thupten Jinpa, Ph.D.

This event at Lehigh University, Pennsylvania, marked the culmination of a 12-year effort by the Tibetan Buddhist Learning Center (TBLC), New Jersey, to translate the Great Treatise into English.

These transcripts were kindly provided to LYWA by the Tibetan Buddhist Learning Center, which holds the copyright. The audio files are available from the Tibetan Buddhist Learning Center’s Resources and Linkspage.

The transcripts have been published in a wonderful book, From Here to Enlightenment, edited by Guy Newland and published by Shambhala Publications. We encourage you to buy the book from your local Dharma center, bookstore, or directly from Shambhala. It is available in both hardcover and as an ebook from Amazon, Apple, B&N, Google, and Kobo. http://www.lamayeshe.com/article/chapter/day-one-afternoon-session-july-10-2008