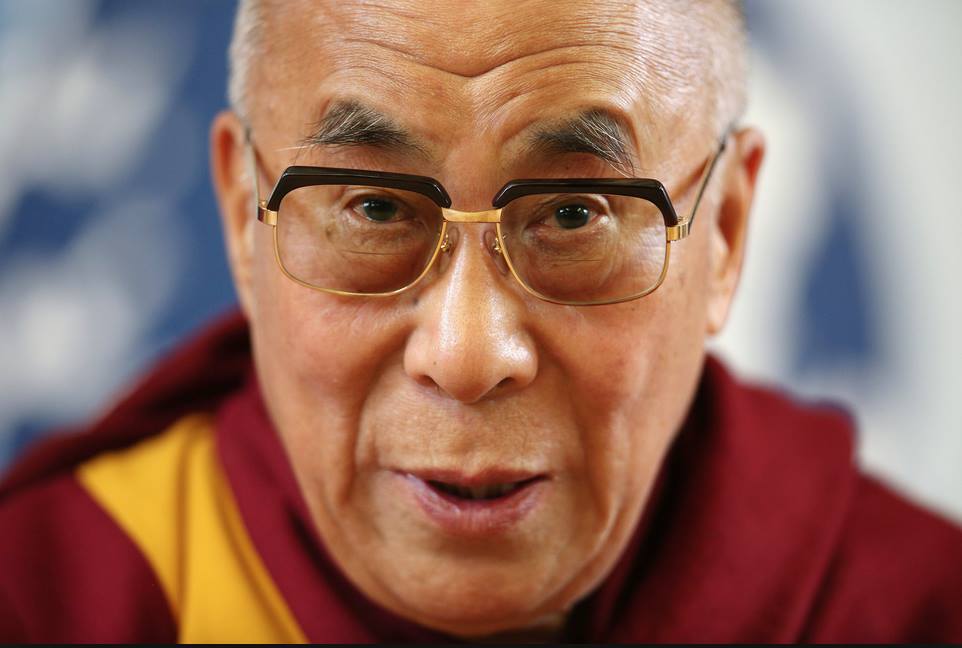

His Holiness the Dalai Lama: When the meditation object is explained in general, four main types of objects are identified.

12. Day Five, Morning Session, July 14, 2008 at Lehigh University, Pennsylvania, USA. Part one. Becoming a Buddha. Tranquil Abiding and Special Insight. Preconditions for Tranquil Abiding. Meditation Posture. Flawless Concentration: The Five Faults and their Eight Antidotes. Choosing an Object of Meditation.

His Holiness: [Chanting in Tibetan]

His Holiness: Now we… Buddhist refuges are Buddha, Dharma, Sangha. So we usually recite buddha saranam gachame, dharma saranam gachame, sangha saranam gachame. Or namo buddhaya, namo dharmaya, namo sanghaya.

Now Buddha, or Dharma, Sangha…[continues in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So when we speak about the three jewels—Buddha, Dharma and Sangha—as objects of refuge, they can be the causal objects of refuge and resultant objects of refuge.

His Holiness: So the very purpose to pray to Buddha is oneself ultimately to become buddha. So from the Buddhist viewpoint, our final destination is buddhahood.

The seed of Buddha—the subtle mind. With its very nature—absence of independent existence. So you see, that very nature—at the basis of change. And that also is the very fact, the very factor leading to the possibility of elimination of all wrong views.

So now, in order to achieve buddhahood, firstly we should achieve sangha—sangham saranam gachame. Now what is the real sort of qualification of Sangha, becoming Sangha? It’s Dharma. [continues in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So what qualifies someone as having attained the state of Sangha is the realization of the true Dharma within. And Dharma here is the truth of cessation—true cessation—and the path leading to the cessation. So the instant one has actualized the path within oneself, then at that point one has become a Sangha.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So when we speak of the three jewels and the Sangha here, at the initial stage is the Sangha status on the “learner” stage. And then, of course, when you become fully enlightened you become “no more learners,” you attain the “no more learners” stage.

However, if we look at it from the point of view of resultant objects of refuge, the three jewels, then as Maitreya points out in his Sublime Continuum (Uttaratantra) where in fact the Buddha himself can be seen as the embodiment of all the three jewels—Buddha, Dharma and Sangha.

His Holiness: So from this level to buddhahood, the way to…the way of progress…

Thupten Jinpa: …progress…

His Holiness: …that’s the gate gate paragate parasamgate bodhi soha. Now that’s the way.

So sometimes I jokingly, you see, am telling people gate gate paragate parasamgate bodhi soha also has the meaning of this physical sort of life. Young child, then later… [continues in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: …A teenage youngster.

His Holiness: Then… [continues in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: And then prime of youth.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: Sorry, then middle age, and then old age.

His Holiness: So gate gate paragate parasamgate – bodhi soha means death. In that case, our final destination is those cemeteries…

Thupten Jinpa: …cemeteries.

His Holiness: That’s our final destination. So we already, I think, are at the stage of, perhaps in my case, I think fourth already. Some of these young people maybe third or second, like that. So that’s nothing, nothing valuable, nothing sacred.

So therefore now gate gate paragate parasamgate bodhi soha must be this mind, the ordinary present—our mind.

Although the desire for happiness—always there. The desire to overcome suffering— always there. But the seed of suffering—within us. All the creators of these problems— within us.

So we have to eliminate, you see, these things. This is the possibility—even with [this] lifetime. I think if you seriously experiment, you gain some experience. So that gives us conviction. Ah! There is a possibility –gate gate paragate parasamgate bodhi soha—on the mental level. It is possible!

So…

Tranquil Abiding and Special Insight

His Holiness: [continues in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So for this ordinary level of mind to move forward to progressively higher states, as explained before, the most important elements that we need to cultivate are the practices of tranquil abiding… sorry, the union of tranquil abiding and special insight—shamatha and vipassana.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So now we will read from book three, volume three.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So the third section of Lam-rim Chen-mo opens with a salutation that, “I pay respectful homage at the feet of the venerable… those venerable masters who are embodiments of great compassion.” And then it opens by stating that the manner in which… the way in which one trains in the last two perfections is as follows.

So earlier we were talking about how the training in the practices of the three higher trainings constitutes the heart of the path to liberation. So within that context, the practice of cultivating calm abiding (tranquil abiding) and special insight belongs to the higher training in meditation and higher training in wisdom.

And in the context…if we relate this to the context of a practitioner aspiring for attainment of buddhahood, then the structure of the path is presented within the framework of six perfections. And in that framework, the cultivation of tranquil abiding and special insight belongs to the last two perfections: perfection of concentration and perfection of wisdom.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So this section Tsongkhapa divides into the following broad outlines, where he lists them as the following:

1. The benefits of cultivating serenity and insight

2. How tranquil abiding and insight include all states of meditative concentrations, and

3. The nature of tranquil abiding and insight, and

4. Why is it necessary to cultivate both, and

5. How to be certain about their sequence.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So we will now read from the section that deals with the explanation of the method by which one trains in these two practices individually.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So this is then is divided into three sections:

The method of training in the cultivation of tranquil abiding;

The method of training in the cultivation of special insight; and

How to unite the two.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So when we talk about cultivating tranquil abiding and special insight, we need to understand that actually what we are talking about is, essentially, cultivation of faculties that are naturally present within our mind.

If you observe… if we observe our states of mind, within our cognitive experiences we will see that there is, for example, within our mind a certain quality of our mind which enables us to maintain our focus on a chosen object and allows us to retain that attention. And that aspect of our mind is the quality of concentration.

And similarly within our mind, naturally, we also possess the ability to differentiate and discriminate various… differentiate various characteristics of the chosen object. So that aspect of the quality of our mind is intelligence—the faculty of intelligence—or wisdom.

So when we are talking about the practice of tranquil abiding and special insight, essentially what we are doing is to really develop those natural faculties that we have and to perfect them.

Preconditions for Tranquil Abiding

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So now in the case of the first practice, which is tranquil abiding, essentially, as explained before, what we are doing is to try to develop that natural faculty that we have, which enables us to retain our attention on a chosen object. So what we are trying to do is to apply effort, and by applying effort, to develop that faculty, that quality of our mind, and cultivate familiarity with that process.

And in this way that quality of our mind becomes more and more developed and enhanced. Because this quality of our mind, being part of the phenomena that belongs to the conditioned domain, therefore it is a phenomena that is dependent upon, contingent upon, its causes and conditions. So therefore the more we cultivate the conditions that would give rise to it, the more effective and powerful that quality of the mind will become.

So that essentially, in the actual practice, what is required is constant application of our faculty of mindfulness and faculty of awareness, or meta-awareness, samprajnana, shay shin. And, in addition to this, one also needs to remove the obstacles that come in the way of our cultivation of this… development of this faculty. And at the same time create the right conditions, seek the right conditions that would enhance the development of that natural faculty. So these practices fall under the heading of what is called seeking the prerequisites—seeking the prerequisites for cultivating tranquil abiding.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So with respect to the prerequisites that one must seek to cultivate tranquil abiding, such as seeking a place of solitude, having the favorable conditions at easy disposal, easy access and so on—in Asanga’sSravakabhumi (Levels of the Disciple) he lists thirteen such prerequisites for the cultivation of tranquil abiding. However, in Kamalashila these thirteen prerequisites are kind of summarized and presented in the list of six prerequisites.

In Tsongkhapa’s Lam-rim Chen-mo, when he talks about the prerequisites for cultivating tranquil abiding, he cites from Asanga’s text. However Asanga’s text, list, includes those four practices which Tsongkhapa has already described in Lam-rim Chen-mo in the context of post-meditational period practices such as: maintaining a healthy kind of appropriate eating habit, food habit; and relation to one’s sleeping patterns; and guarding one’s doors of the senses; and acting in the world with a greater sense of awareness. These were already explained in the section dealing with the practices of the after-session periods.

Meditation Posture

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So Tsongkhapa then explains the actual practice of cultivating tranquil abiding in the two main outlines: he says, “How to cultivate serenity on that basis” which is divided into two: which are “Preparation” and the “Actual Practice.”

Then in the section on the preparation he explains how to develop the meditative posture and the actual meditative process.

So the first outline deals with the need to adopt an appropriate physical posture. And since, in the practice of tranquil abiding, our main aim is to develop and cultivate and enhance our single-pointedness of our mind, therefore the physical posture really has a big impact. So, for example, if you try to do the practice by lying down instead of sitting upright, then the fact of lying down tends to bring your mind to a much more relaxed, kind of, you know, lazy state. So therefore it’s better to keep your body upright.

And traditionally, when explaining the appropriate posture for meditation, one speaks of the seven-fold posture of Vairocana. Sometimes, when you add the respiration process, we call it the eight-fold posture of Vairocana.

1. The posture of your legs. And the legs can be either completely cross-legged or half cross-legged as you normally would sit. And, in any case, you need to adopt a posture that is… for your legs that does not put too much strain on your knees. Otherwise you will lose your focus. So that is one.

And then your hand posture, you can put…perform the meditation gesture with your left palm underneath and placing your right palm on top of it. And if you relate it to the posture according to the Vajrayana practice, then the preferred position is to have your two thumbs touching each other so that it forms a triangular shape there. So that’s how the…

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: And your two arms should not be touching your body but rather kept slightly outstretched so that also next to your… also between your two arms there forms a natural triangular shape.

1. And then the next is your spine. And the spine should be kept straight. And the text describes the kind of posture as like, “Your spine should be straight as an arrow.”

2. And then the next one is your teeth. And, but you should keep them in a natural state. Don’t grit your teeth but rather keep them natural. And if you don’t happen to have teeth then you have no choice anyway. And then for your lips, again you should keep them in a natural posture.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: In fact those who do not have teeth, you know, their lips look quite impressive because they’re kind of, slightly stretched.

And then the next is your eyes, and the text says that we should keep our eyes slightly downcast, focused upon the…at the level of the tip of our nose. So if you have a large…

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: Sorry, the tongue should be…

His Holiness: Lips

Thupten Jinpa: Yes…

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So you keep your lips in their natural position. Don’t force any posture on them.

4. And then next is the tongue. The recommendation is to keep it slightly curled so that you touch the upper palate of your…the roof of your upper palate. And the advantage of that is that, for example, if you happen to really enter deeply into a meditative state, then this posture will protect you from having saliva drooping down. And also because of that, the position of the tongue, it has a natural effect of making your breathing less forceful. So that also has a benefit of ensuring that your mouth doesn’t get unnecessarily dry. So those are the reasons why you keep your tongue in that position.

5. And next is the position of the eyes, so you keep them slightly downcast and glancing at the point of the tip of your nose. And if you happen to have a large nose rather like Joshua Cutler, then you wouldn’t have a problem because you can see the tip of your nose quite easily. But if you are like the Asians, like Vietnamese, Chinese or Tibetans, then you would have a rather flat nose. Then you shouldn’t really try hard to see the tip of your nose because that is going to cause so much strain on your eyes. So basically keep it kind of slightly downcast.

6. And then next is… the position of your head, again, slightly bent, and…

His Holiness: Closed eye or open eye, just natural. [continues in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: Natural.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So as to the position of your eyes, as much as possible you should keep them in their natural position, slightly downcast and not deliberately close them. Because if you close them and do your meditation, then the moment you open your eyes, then your meditation gets disturbed.

In fact since a meditative state is being cultivated at the level of the mental consciousness, not at the level of the sensory experience, therefore when you meditate with your eyes slightly open and kept in the natural state, once in a while naturally they will close, but then that’s okay. But keep it kind of natural.

And so that if you learn that habit, then because the meditation is taking place at the level of mental consciousness, after a while, because of being in that state, whatever happens to be in the field of your vision will not affect you, because you become in a sense kind of oblivious to the sensory stimuli. Rather you’ll be able to maintain, and remain in, that meditative state. So in other words, don’t try to keep them closed, just keep it naturally. And when you occasionally close them that’s fine, but keep it natural.

And then the position next is the position of the head, slightly bent.

1. And then, finally you have the position of the shoulders, and keep them slightly again natural but slightly extended.

2. And then finally is the breathing process. Again the breathing should not be too harsh or too slow, but rather again at a natural pace.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So, on page 31, Tsongkhapa actually describes what kind of pace of breathing that you should avoid in the context of tranquil abiding meditation. And he writes in the second para , “Your inhalation and exhalation should not be noisy…” so that when you breathe there is a lot of noise; or “…forced…” so that you are breathing too deeply as if it is coming out of your abdomen; “…or uneven…” so, you know, in other words he says, “…let it flow effortlessly, ever so gently, without any sense that you are moving it here or there.”

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: However, one must bear in mind that, in different instructions on meditation, slightly the positions will differ, for example, particularly the eye position.

Here Tsongkhapa is describing the posture of the eyes in the context of general meditation practice of cultivating tranquil abiding. But in other contexts, for example in the Kalachakra Tantra, then the posture of the eyes are recommended to be kept really looking upwards and then you know, keeping your eyes open and looking upwards, whereas in Dzogchen meditation, you look straight in front of you. So depending upon the context, the instructions on some of the postures will differ.

Flawless Concentration: The Five Faults and their Eight Antidotes

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So then the second outline, the actual “Meditative process”, is described in the following sub-headings.

Tsongkhapa explains them: “How to develop flawless concentration” and “What to do while focusing”, sorry, what should… “Who should meditate on which objects,” “Synonyms of the objects of meditation…object of meditation” and so on.

So within the first outline he explains this, “What to do prior to focusing the attention on the object of meditation;” “What to do while focusing on the object” and “What to do after having focused one’s attention on the objects”.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: In the actual explanation of how to cultivate the flawless concentration, Tsong kha pa proceeds with the citation from Maitreya’s Differentiation of/Discrimination of the Middle and the Extreme. In this text Maitreya speaks of five flaws of meditation and the eight antidotes against these faults.

The five faults are listed as: a form of laziness or indolence; and forgetting of the object; and mental excitement/excitation and mental laxity as counted as one; and the fourth is failing to apply the antidotes when mental excitation or mental laxity arises; and then the fifth one, fifth obstacle or fault, is excessive application of exertion.

Especially at more advanced levels when the quality of the mental stability is very firm, then in those moments, in those stages, then application of effort in fact becomes counter-productive, so therefore one needs to maintain a state of equanimity. So inappropriate application of effort or exertion is also a fault.

Corresponding to these five faults, eight antidotes are identified. So in relation to the first fault, which is laziness or indolence, Asanga lists four antidotes. These are faith or confidence, and aspiration, and effort, and pliancy.

And the faith here refers to a kind of a feeling of trust in the quality and benefits, based upon the awareness of the benefits of meditative stabilization and so, and particularly by reflecting upon the benefits which are the physical and mental suppleness. Because when you attain meditative stabilization it leads… it gives you physical and mental pliancy that enable you to make your body and mind serviceable. And so this… and also you can apply your body and mind at your will.

So these are, of course, benefits of concentration which are common to both Buddhist and non-Buddhist practitioners. So since here, in this lam-rim context, we are cultivating tranquil abiding with the ultimate aim of applying it to our understanding of the ultimate nature of reality—because without tranquil abiding, vipassana, the special insight, cannot arise—so we recognize the special benefits of having gained tranquil abiding. So by reflecting upon these qualities then you develop kind of a deep trust in the efficacy and in the benefits of meditative concentration. So this is what is meant by faith or trust.

Second is, based on that trust or faith, the interest, aspiration, to cultivate that state arises in you. And then on the basis of the aspiration and interest brought forth by this confidence and trust, then your willingness to apply the effort will arise. So in this way, the problem of the fault of laziness or indolence is overcome.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So with relation to the second fault, which is forgetfulness, forgetfulness of the object of meditation—the main antidote here is the cultivation of mindfulness.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: And corresponding to the third fault, which is the mental excitation and mental laxity, when they arise, the antidote that needs to be applied is meta-awareness, awareness, or meta-awareness, samprajnana.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So with respect to the fourth fault, which is the failure to apply the necessary antidotes when excitation and laxity arise, the antidote to that is the cultivation of the intention to apply it.

And the fifth fault, which is the inappropriate application of exertion or effort… and here, because in some contexts the application of effort is counter-productive because it could undermine the quality and stability of the meditative state, therefore here the counterforce is cultivating equanimity.

Choosing an Object of Meditation

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So then Tsongkhapa explains the next outline, which is what to do at the moment when you are focusing your mind on the object of attention. And this is explained in terms of two sub-headings: first “identifying the object of meditation”; and the second, how to apply one’s attention to those objects.

So in the context of identifying the appropriate object of one’s concentration, generally in the text… in general one can choose for one’s object of meditation any external or internal phenomena. For example, one can choose just a pebble or a twig or a stick as an object of meditation to cultivate single-pointedness. Similarly one can choose an internal mental state such as an experience of a feeling as an object of meditation, and cultivate single-pointedness on that basis. For example, if you look at the teaching on the four foundations of mindfulness, the foundation of mindfulness on body, on feelings, on mind, and on mental objects, you can see that these meditations include both external and internal objects as the object of one’s meditation.

However when the meditation object is explained in general, four main types of objects are identified. One is referred to as the pervasive object, and second is the object that is appropriate to the experience or emotional temperament of the individual practitioners. So here the point is that due to whatever factors past or present, individuals may have different temperaments, emotional kind of styles. And whatever emotion type may be more dominant within an individual person, corresponding to that, one needs to choose objects that would be more effective. So that’s the second type of object.

The third type of object is referred to as the object of the wise or the learned. And here it includes those fields of knowledge in relationship to which one is cultivating an understanding. So you choose these objects, including enumerations of lists and stuff, and then cultivate single-pointedness in relationship to them.

And the fourth is a specific object you choose in order to diminish your afflictions. So these are the four main types or classes of objects that are identified.

In July 2008, His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama gave a historic six-day teaching on The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment (Lam-rim Chen-mo), Tsongkhapa’s classic text on the stages of spiritual evolution. Translator for His Holiness was Thupten Jinpa, Ph.D.

This event at Lehigh University, Pennsylvania, marked the culmination of a 12-year effort by the Tibetan Buddhist Learning Center (TBLC), New Jersey, to translate the Great Treatise into English.

These transcripts were kindly provided to LYWA by the Tibetan Buddhist Learning Center, which holds the copyright. The audio files are available from the Tibetan Buddhist Learning Center’s Resources and Linkspage.

The transcripts have been published in a wonderful book, From Here to Enlightenment, edited by Guy Newland and published by Shambhala Publications. We encourage you to buy the book from your local Dharma center, bookstore, or directly from Shambhala. It is available in both hardcover and as an ebook from Amazon, Apple, B&N, Google, and Kobo.

http://www.lamayeshe.com/article/chapter/day-five-morning-session-july-14-2008