5 His Holiness The Dalai Lama: Commentary on The Precious Garland “Ratnavali” by Nagarjuna, UCLA Los Angeles 1997.

All of Nagarjuna’s works were written in verse, though I don’t know if you could say they are poetry per se, and certainly they are not as poetic as many of Shantideva’s verses. Nagarjuna was primarily a logistician and his dialectic is often described as a form of reductio ad absurdum (Latin: “reduction to the absurd”), the method of pointing out the contradictory or absurd consequences of an opponents argument. Although, Nagarjuna maintained that “If I would make any proposition whatever, then by that I would have a logical error; but I do not make a proposition, therefore I am not in error.”

Karl Jaspers wrote, “Nagarjuna strives to think the unthinkable and to say the ineffable. He knows this and tries to unsay what he has said. Consequently he moves in self-negating operations of thought.” On the surface, it appears that Nagarjuna’s logic is rather negative, however, as many have pointed out, it would be a mistake to brand it as nihilism.

Here is more of the Dalai Lama’s teachings on one of Nagarjuna’s most famous works. In this transcript, I have only included those verses that were read aloud to the audience. If you would like to read the verses the Dalai Lama refers to, or the entire work, go here. It’s not the same translation as was used at the teachings, but the differences are minor.

The Free Tibet Network has reported that Tsewang Norbu, a 29-year old Buddhist monk died Monday after setting himself on fire on 08. 15. 2011 in protest against the continuing Chinese crackdown on Tibetan monks. According to witnesses, as he set himself ablaze, the monk shouted, “We Tibetan people want freedom,” “Long live the Dalai Lama” and “Let the Dalai Lama return to Tibet.”

@page { margin: 2cm } p { margin-bottom: 0.25cm; line-height: 120% }

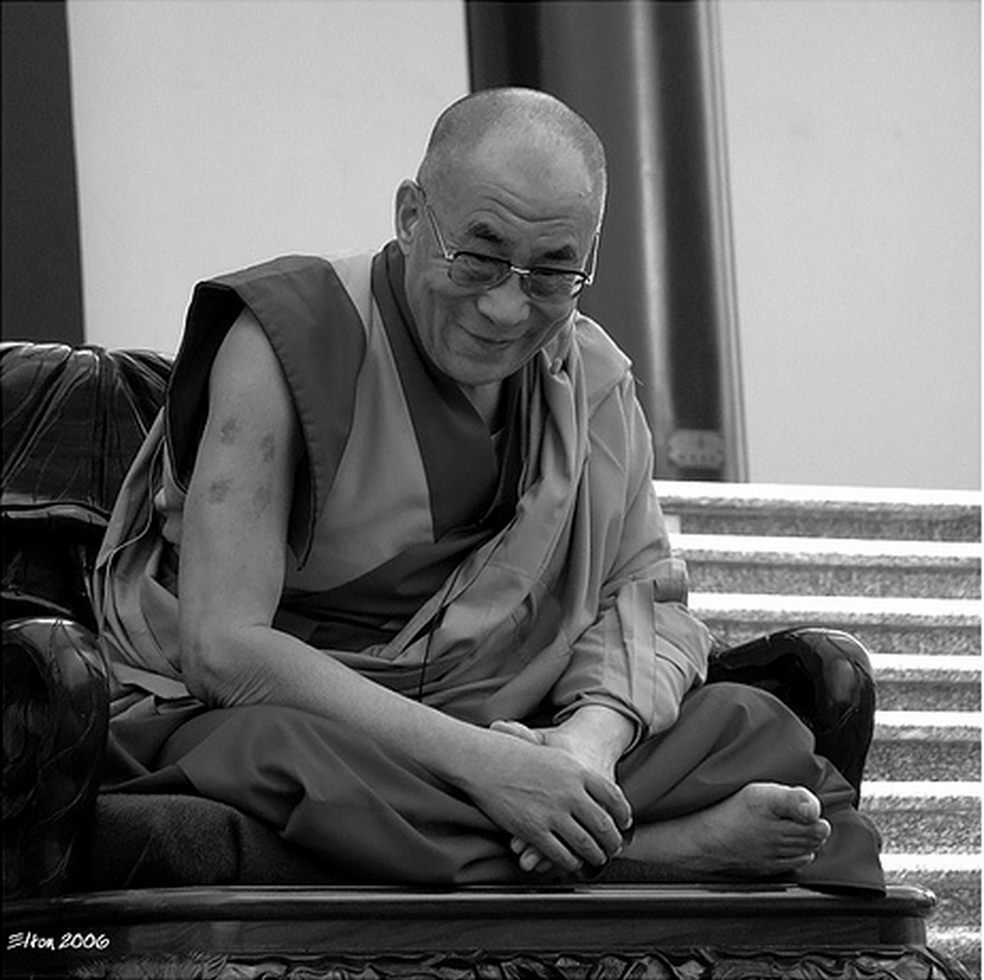

Tenzin Gyatso, His Holiness the Dalai Lama

In the next two verses, the text defines what are the ten non-virtuous acts: violence, theft, adultery, lying, divisive speech, harsh words, idle talk, miserliness, maliciousness, and nihilistic views. It says there are ten bright paths of action and that the reversal of the virtuous actions are the ten negative actions.

In verse 10, Nagarjuna, in addition to the list of positive actions, gives a list of another six dharmas: three dharmas of avoidance and three dharmas of acceptance [not drinking liquor, maintaining a proper occupation, abandoning harm, being respectfully generous, honoring the worthy, and cultivating love].

The point of identifying these as the dharma here is to insure that the individual does not give any opening to negative actions or engage in negative activity. These are said to be the 16 Paramitas [Perfections], the ten positive actions plus the six dharmas, the 16 Paramitas is aimed at attaining the elevated states of existence, which means higher forms of rebirth.

Given the adoptions of these positive actions are constituted by abstaining from their opposite forces, what is important is to abstain from these negative actions throughout one’s entire life. If not, at least avoid them as much as possible. Even in the event that we find ourselves engaging in these negative actions, what is important is that we insure that our thoughts are influenced by repentance, so that we won’t take pleasure in the commitment of these deeds, so that there is no degree of indifference, because if someone has no regard for what happens in engaging in these acts, to such a person it is said that there is not even a smell of a good, practicing Buddhist.

So in verses, 11, 12, and 13, the text emphasizes the fundamental point that dharma activity by nature must be a beneficial activity. Because the essence of dharma is to be of benefit to oneself and others. If it is an activity that involves inflicting pain on others or on oneself, such forms cannot be considered as being the dharma of liberation or dharma that leads to higher forms of rebirth. In these verses, the text defines that if in engaging in such physical austerities, pain is inflicted on oneself or others, then it is not dharma at all.

Whenever I give instructions in Buddhism, I always tell people that the entire teachings of the Buddha could be summarized in two principles: one is the cultivation of the view of the interdependent nature of reality, and two is adopting a form of behavior that is not harming others. Those two principles capture the entire essence of the Buddha’s teachings.

The next set of verses address the question that sometimes one might wonder how murder and stealing and telling lies can be said to be negative in the sense that they cause pain, because certain things, which are said to be negative, can also bring a degree of satisfaction to the individual. For example, someone who has committed a murder or someone who has stolen something might, for a short time, feel satisfaction. So one could argue that these actions may not always be negative.

Nagarjuna addresses that question by showing how all these actions are negative and lead to undesirable consequences with the individual, and he suggests that in verse 18 that “prior to all of these there is a bad rebirth,” suggesting that these negative actions – if the deeds are done with strong emotion, great intensity and cool, calculated motivation, then the karmic result of these acts leads to rebirth in lower states of existence, even if one is reborn as a human being, these acts lead to undesirable consequences. This is described in verses 14 through 19.

The last verse indicates that when you refrain from these negative actions, you can have positive results, if you abstain from murder, you will have a long life span. If you abstain from violence, you will not be an object of violence.

Verse 20 of the text summarizes what is meant by negative or non-virtuous actions, and positive or virtuous karma, in terms of negative or positive in the sense that an action leads to liberation or not.

The next several verses summarizes the definition of what is meant by negative action and what is positive action, on the basis of what kind of effect it produces. Those actions which produce happiness and positive rebirth are virtuous. There are three doors from which actions are committed: body, speech, and mind. The text says that the dharmas given here are to be committed in observance of the right kind of code of ethics for body, speech, and mind. Then it reads that if one engages in such a dharmic way of life, not only will one attain higher forms of existence in the next life, but within that life one will also gain results like happiness and less suffering.

Verse 24 explains that within the realm of enlightened states, there are more elevated states of existence corresponding to the levels of consciousness and subtlety of concentration. And also there are said to be four levels of concentration and formless realms, regardless of whether or not they exist in the objective world. However, it is true as we approach deeper into the more subtle levels of consciousness there is a degree of tranquility, a corresponding level of freedom from the conceptual restlessness that seems to dominate our minds in the ordinary states of existence. So, compared to thoughts of the individual in the realm of existence, those individuals abiding in the formless realms are said to be at a level where these is a degree of tranquility and freedom from the gross levels of affliction of the mind, delusions and so on.

Within the formless states there are different levels of subtlety. For example, in the scriptures, there is a mention of a formless state which is said to be infinite space. Then the next state is infinite consciousness, which is even more subtle than infinite space, and next is the state of non-observation of nothingness, that is said to be more subtle than the state of infinite consciousness. And the highest level of formless realms is sad to be the most subtle.

The point is that as a result of engaging in different forms of concentration and absorptive meditation states of mind, one can attain corresponding subtleties of consciousness.

In the Prajna Paramita [“Transcendent Wisdom”] Sutras, there is mention of different yanas or vehicles. There’s discussion of human vehicles and deva [“radiant ones”] vehicles and Brahma [in this context, the ultimate divine reality] vehicles. And all the practices within the cultivation of these form and formless realms are said to be the Brahma vehicle, referring to levels of tranquility. The practice of the ten virtuous actions and the six dharmas that we spoke of earlier can be said to be part of the human yana or vehicle. And corresponding to the diversity of conceptual qualification, there are diverse forms of yana or existence.

Do we have the questions ready? [The answer is no]. So in that case, I will continue to read from the text and you can prepare the questions for tomorrow. You can write down the questions on a piece of paper and give them to the usher and tomorrow we will deal with them in one of the sessions.

But the Victors said that

the Dharma of the highest good

is the subtle and profoundly appearing;

it is frightening to unlearned, childish beings.

From verse 25 the discussion moves on to the dharma and three associated practices related to the attainment of what the text calls the highest good. The highest good here refers to liberation or nirvana. And it is said to be the highest good in the sense that liberation constitutes the definitive attainment and happiness and it is also positive in all its aspects.

Now the question is why is liberation or nirvana said to be the highest good? Here my explanation is from the point of view of the Madhyamaka [the Middle Way school of Nagarjuna] philosophy. It is said to be the highest good because liberation or nirvana is constituted by the total overcoming or elimination of the state of existence that is characterized by ignorance and the bondage of clinging to self. So long as one remains in a state where one is clinging to self-existence, there is no real scope for lasting joy or happiness because such an individual remains in the bondage of karma and afflictions of the mind. Therefore, any effort toward total freedom from that kind of bondage really constitutes the highest form of attainment.

When the Buddha taught the Four Noble Truths, he taught the first truth, the truth of suffering, in terms of description of the four characteristics of suffering. The first being impermanence. The fact that existence in the unenlightened states is transient, ultimately unsatisfying, there is emptiness [Skt. Sunyata] and there is an absence of self-existence. When we talk about impermanence, in a conventional sense, one can have a rough understanding in terms of the continuum of life. But that is a coarse understanding of the transient nature.

The transient nature being taught here as one of the cardinal characteristics of existence should be viewed in terms of its dynamic process, its ever changing nature. It is momentary but even in the individual instances themselves, the moment they come into being are in the nature of disintegration. It is not as if things come into being first and then some third condition or some other factor cause it to cease to exist. It’s not the case. Whatever phenomena comes into being, the very instant they are born, they are born with the full mechanism for their disintegration.

One could say that the very cause that creates them also creates the destruction of the phenomena, so that the seed or mechanism for disintegration is built within the phenomena itself. So now, we apply that subtle meaning of impermanence to ourselves in an unenlightened form. We are then talking about an understanding of the causal process, where the two primary causes are negative karma and afflictions of the mind. Underlying all of the afflictions of the mind is the cardinal root cause, which is described as avidya or ignorance.

The very word avidya or ignorance in itself show a state that one cannot really endorse as positive. It is said to be fundamentally confused, so, surely it cannot be a state that is desirable. The point is that if our existence is said to be completely determined and conditioned by that fundamentally flawed way of viewing the world, how can there be scope for lasting freedom or lasting peace. Therefore, it becomes crucial to see whether that advidya or fundamental ignorance can be eliminated.

Now, of course, within the Buddhist tradition there are divergent opinions as to what is the nature of ignorance. Such masters as Asanga [Buddhist philosopher who was the creative force behind the Yogacara school and the “Mind-Only” doctrine] made distinctions between self-grasping – the mind grasping at self-existence on one hand and ignorance on the other. Asanga, and others like him, saw ignorance more in terms of an inactive state, a mere not-knowing, where other Buddhist thinkers such as Dharamkirti [a Buddhist logician] and many Madhyamaka philosophers defined ignorance as an active state of mis-knowing, relating to the world in a distorted way of perceiving. In that sense, the self-grasping mind itself is the fundamental ignorance. From the last point of view, the quest for freedom from Samsara [the cycle of birth and death fueled by ignorance] really becomes the quest to dispel ignorance and its mortal apprehension.

One could say that this fundamental ignorance is the definitive enemy within us. As Shantideva’s Bodicaryavatara, or “Guide to the Bodhisattva Way of Life”, points out, the power and the extent of harm that the internal enemy can inflict upon us should cause us to view ignorance as the most definitive and inner-most enemy that we combat.

When we talk about ignorance, we must know that, to a large extent, it is something that is natural and innate within us and sometimes this naturally flowed way of viewing life can be reinforced by philosophical speculation. So when the Buddhist teaching of anatma or no-self is taught, often it can create a sense of unease within us. Because the grasping for self-existence is so deeply rooted in us, reflection on the fundamental Buddhist teaching of anatma can create some discomfort. Especially for those in whom this inherent self-grasping is further reinforced by metaphysical speculation – for them the sense of discomfort or unease can be even greater.

I can tell you a story about an Indian from Bihar, who later became a Buddhist and part of the monastic order. One day I was teaching to him the doctrine of anatma, no-self, and when I mentioned to him that Buddhism rejects the concept of a soul, the person was literally shaking. So this shows how a genuine reflection of this most basic Buddhist teaching of no-self can go against the deeply imbedded ways of viewing the world that we possess.

This is what is meant by verse 26, where it reads, “the teaching of selflessness terrifies the childish./For the Wise, it puts an end to fear.”

For the wise, the teaching of selflessness really shows that there is an opening to getting out of this condition of being in an unenlightened state of existence.

In verse 27, it reads that,

All beings arise from fixation on self

such that they (thereby) are fixated on ‘mine’;

this is what has been stated

by the one who speaks solely for the sake of beings.

Given that it is this grasping at the concept of self-existence which gives rise to the unenlightened forms of existence, the Buddha has taught, out of compassion for all sentient beings, the path which would liberate all out of that bondage. The path here refers to the path of no-self.

So we will leave at that. Those of you who have deeper interests in what we have discussed so far, I would suggest that you reread the sections that we have covered today and try to reflect on their meanings. So, through this way, you will gain greater benefit.

Since the process of understanding takes place in the form of attaining different levels of understanding, and in the scriptures there is a description of a procedure where one arrives at an understanding derived through study and listening and which can then develop into the second level of understanding, which is contemplation, which goes to the third level of understanding-through-meditation. In the first level of study, listening and hearing, what is important is to be able to train and focus when listening and studying so that one can deepen one’s insight. So this is why in the sutras there is the advice that you should listen well and then put what you have heard into heart. So, it is listening well and the using one’s faculty of mindfulness that one can then put into memory what one has learned.

Both knowledge and mindfulness are very important in insuring that we are successful in living a life-style which is in the bounds of an ethically disciplined way of life. So when we talk about mindfulness [Pali: anapanasati, literally, mindfulness of breath], we are not always talking about being self-conscious, but rather an underlying alertness. So that we are ever-vigilant, so that when we are confronted with situations that demand an ethical judgment, because of our underlying mindfulness, we are instinctively able to respond in the right manner, and therefore, without knowledge we won’t know how best to act or what ethical way to act. So when there is knowledge, but no mindfulness, then that knowledge is not beneficial, so you need both knowledge and mindfulness.

So that is all, we will end the session with a prayer of dedication.

[The Dalai Lama leads the monks on stage in chanting a short prayer in Tibetan.] [in English] Thank you, good night. [Applause] END OF DAY ONE http://theendlessfurther.com/tag/the-precious-garland/page/2/