Sua Santità il Dalai Lama: La consapevolezza che siamo fondamentalmente gli stessi esseri umani, che cercano la felicità e cercano di evitare il dolore, è molto utile per sviluppare il senso di fraternità e il caldo sentimento d’amore e di compassione per gli altri.

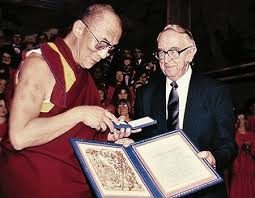

Nobel Lecture per il conferimento del premio Nobel per la pace a Tenzin Gyatso, Sua Santità il XIV Dalai Lama del Tibet, Oslo, 11 dicembre 1989

Fratelli e sorelle.

È un onore e un vero piacere per me essere oggi qui tra voi.

Sono veramente felice di vedere tanti vecchi amici giunti dai più remoti angoli del mondo e di vederne di nuovi che mi auguro di incontrare ancora in futuro. Quando incontro delle persone nelle diverse parti del mondo, questo mi ricorda sempre quanto siamo sostanzialmente uguali: tutti esseri umani; forse vestiti in modo diverso, con la pelle di colore diverso, che parlano lingue differenti. Ma questo è solo ciò che appare in superficie, fondamentalmente siamo gli stessi esseri umani e questo è ciò che ci lega l’uno all’altro. Questo è ciò che ci consente di comprenderci l’un l’altro, di fare amicizia e sentirci vicini.

Riflettendo su ciò che potrei dire oggi, vorrei condividere con voi alcuni miei pensieri relativi ai problemi comuni che noi tutti dobbiamo affrontare come membri della famiglia umana. Tutti condividiamo questo piccolo pianeta e dobbiamo imparare a vivere in armonia e in pace sia l’un l’altro che con la natura. Questo non è un sogno bensì una necessità. Dipendiamo l’uno dall’altro in molteplici modi, tanto che non possiamo più vivere in comunità isolate e ignorare nel frattempo ciò che sta succedendo al di fuori di queste comunità. Dobbiamo aiutarci l’un l’altro quando abbiamo delle difficoltà, e dobbiamo condividere la buona fortuna di cui godiamo. Vi parlo come un semplice monaco. Se troverete utile quello che dirò, sperò che cercherete di metterlo in pratica.

Oggi desidero anche condividere con voi i miei sentimenti relativi alla condizione e alle aspirazioni del popolo del Tibet. Il premio Nobel è un premio che essi ben meritano per il coraggio e la determinazione dimostrati durante gli ultimi cinquant’anni di occupazione straniera.

In quanto libero portavoce dei miei concittadini, sento come mio dovere di parlare a loro nome. Non parlo con un sentimento d’ira o di rancore per coloro che sono responsabili dell’immensa sofferenza del nostro popolo e della distruzione della nostra terra, delle nostre case e della nostra cultura. Anch’essi sono esseri umani che si sforzano di trovare la felicità e meritano la nostra compassione. Parlo per informarvi della triste situazione in cui versa oggi il mio paese e delle aspirazioni del mio popolo, perché, nella nostra lotta per la libertà, la verità è l’unica arma che possediamo.

La consapevolezza che siamo fondamentalmente gli stessi esseri umani, che cercano la felicità e cercano di evitare il dolore, è molto utile per sviluppare il senso di fraternità e il caldo sentimento d’amore e di compassione per gli altri. Questo è a sua volta essenziale soprattutto se vogliamo sopravvivere nel mondo in cui viviamo, un mondo che diventa ogni giorno più piccolo.

Questo perché, se ciascuno di noi perseguisse egoisticamente ciò che pensa essere il suo proprio interesse, senza curarsi dei bisogni degli altri, potrebbe finire col fare del male non solo agli altri ma anche a se stesso. Questo fatto è diventato molto evidente nel corso di questo secolo. Sappiamo, per esempio, che oggi scatenare una guerra nucleare sarebbe una forma di suicidio, e che inquinare l’aria e gli oceani per ottenere qualche beneficio a breve termine sarebbe distruggere la base stessa della nostra sopravvivenza futura. Via via che gli individui e le nazioni diventano sempre più interdipendenti, non abbiamo altra scelta che quella di sviluppare quello che io chiamo un senso di responsabilità universale.

Al giorno d’oggi siamo veramente una famiglia globale.

Ciò che accade in una parte del mondo può influire su tutti noi. Questo, ovviamente non è vero solo per le cose negative che accadono, vale anche per gli sviluppi positivi.

Non solo sappiamo ciò che accade altrove, grazie alla straordinaria tecnologia moderna delle comunicazioni: siamo anche direttamente influenzati da eventi che accadono molto lontano.

Proviamo un senso di tristezza quando dei bambini muoiono di fame nell’Africa orientale. Analogamente, proviamo un senso di gioia quando una famiglia è riunita dopo decenni di separazione a causa del muro di Berlino. Le nostre messi e il nostro bestiame sono contaminate la nostra salute e la nostra stessa vita sono minacciate quando ha luogo un incidente nucleare a molti chilometri di distanza in un altro paese. La nostra sicurezza aumenta quando scoppia la pace tra parti belligeranti su altri continenti.

Ma la guerra o la pace, la distruzione o la protezione della natura, la violazione o la promozione dei diritti umani e delle libertà democratiche, la povertà o il benessere materiale, la mancanza di valori morali e spirituali o la loro esistenza e il loro sviluppo, il venire meno o lo sviluppo della comprensione umana, non sono fenomeni isolati che si possono analizzare e affrontare indipendentemente l’uno dall’altro. In realtà, sono molto interconnessi a tutti i livelli e bisogna affrontarli comprendendo innanzitutto questo.

La pace, nel senso di assenza di guerra, è di scarso valore per chi sta morendo di fame o di freddo. Non eliminerà il dolore della tortura inflitta a una persona messa in prigione per le sue idee. Non conforta coloro che hanno perduto i loro cari in alluvioni causate dall’insensato disboscamento in un paese vicino. La pace può durare solo dove sono rispettati i diritti umani, dove la gente è ben nutrita, e dove gli individui e le nazioni sono liberi. La vera pace con noi stessi e con il mondo intorno a noi può essere raggiunta solo attraverso lo sviluppo della pace mentale. Gli altri fenomeni sopra citati sono interrelati in modo analogo. Così, per esempio, vediamo che un ambiente pulito, la ricchezza o la democrazia significano poco di fronte alla guerra, specialmente di tipo nucleare, e che lo sviluppo materiale non è sufficiente ad assicurare la felicità umana.

Il progresso materiale è ovviamente importante per l’avanzamento umano. In Tibet, abbiamo prestato troppa poca attenzione allo sviluppo tecnologico ed economico, e oggi ci rendiamo conto che questo è stato un errore.

Allo stesso tempo, lo sviluppo materiale senza sviluppo spirituale può anch’esso causare gravi problemi.

In alcuni paesi, si presta troppa attenzione alle cose esterne e si dà pochissima importanza allo sviluppo interiore. Io credo che entrambi siano importanti e debbano essere sviluppati fianco a fianco in modo da ottenere un buon equilibrio tra di essi. I tibetani sono sempre descritti dai visitatori stranieri come gente felice e gioviale. Questo fa parte del nostro carattere nazionale, formato da valori culturali e religiosi che pongono l’accento sull’importanza della pace mentale ottenuta grazie a un sentimento di amore e benevolenza per tutti gli esseri senzienti, sia umani che animali.

La pace interiore è la chiave di tutto: se avete la pace interiore, i problemi esterni non influenzano il vostro profondo senso di pace e tranquillità. In queste condizioni di spirito, si possono trattare le situazioni con calma e ragione, mantenendo la felicità interiore. Questo è molto importante; senza la pace interiore, per quanto confortevole sia materialmente la nostra vita, restiamo spesso preoccupati, turbati o infelici a causa delle circostanze.

Chiaramente, è di grande importanza comprendere le interrelazioni tra questi e altri fenomeni dobbiamo perciò affrontare e cercare di risolvere i problemi in un modo equilibrato che tenga conto di questi differenti aspetti.

Questo, ovviamente, non è facile, ma è di poca utilità tentare di risolvere, un problema se così facendo se ne crea un altro altrettanto grave.

In realtà, quindi, non abbiamo nessuna alternativa: dobbiamo sviluppare un senso di responsabilità universale non solo nel senso geografico ma anche per quanto riguarda i diversi problemi presenti nel nostro pianeta. La responsabilità non è solo dei leader dei nostri paesi o di coloro che sono stati nominati o eletti a fare un particolare lavoro, è anche di ciascuno di noi, individualmente. La pace, per esempio, inizia dentro ciascuno di noi. Se possediamo la pace interiore, possiamo relazionare perfetti rapporti di pace con tutti coloro che ci circondano.

Quando la nostra comunità è in uno stato di pace, può condividere questa preziosa qualità con le comunità vicine, e così via. Se proviamo amore e benevolenza per gli altri, questo non solo fa sentire gli altri amati e oggetto di benevola attenzione, ma ci aiuta anche a sviluppare felicità e pace interiori. Ci sono sempre dei modi in cui possiamo lavorare coscientemente a sviluppare sentimenti d’amore e di benevolenza. Per alcuni di noi, il modo più efficace di farlo è attraverso la pratica religiosa. Per altri, può esserlo attraverso pratiche non religiose. Ciò che è importante è che ciascuno di noi faccia un sincero sforzo di assumere sul serio la propria responsabilità per ciascun altro e per l’ambiente naturale.

Sono molto incoraggiato dagli sviluppi che stanno avendo luogo intorno a noi. Da quando le nuove generazioni di molti paesi, soprattutto del Nord Europa, hanno insistentemente chiesto la cessazione della distruzione dell’ambiente condotta in nome dello sviluppo economico, i leader politici del mondo hanno cominciato a fare dei passi significativi per affrontare questo problema.

Il rapporto della Commissione mondiale sull’ambiente al segretario generale delle Nazioni Unite (il rapporto Brundtland) è stato un passo importante nell’informare i governi sull’urgenza del problema. I seri sforzi di portare la pace in aree divise dalla guerra e di far valere il diritto all’autodeterminazione di alcuni popoli hanno portato al ritiro delle truppe sovietiche dall’Afghanistan e all’indipendenza della Namibia. Grazie a persistenti sforzi popolari non violenti, in molti paesi, da Manila nelle Filippine, a Berlino nella Germania orientale, hanno avuto luogo spettacolari cambiamenti, che hanno portato molti paesi più vicino alla vera democrazia.

Con la guerra fredda che sembra avviata alla fine, la gente vive ovunque con rinnovata speranza. Purtroppo, i coraggiosi sforzi dei cinesi di attuare un analogo cambiamento. nel loro paese sono stati brutalmente repressi il giugno scorso. Ma anche i loro sforzi sono una fonte di speranza. Il potere militare non ha estinto il desiderio di libertà né la determinazione del popolo cinese a conseguirla. Ammiro in modo particolare il fatto che questi giovani, ai quali è stato insegnato che “il potere politico nasce dalla canna del fucile” abbiano invece scelto come loro arma la non violenza.

Ciò che indicano, questi mutamenti positivi è che la ragione, il coraggio, la determinazione e l’inestinguibile desiderio di libertà può alla fine vincere.

Nella lotta tra le forze della guerra, della violenza e dell’oppressione da una parte, e la pace, la ragione e la libertà dall’altra, queste ultime stanno avendo la meglio. Questa constatazione riempie noi tibetani di speranza perché forse un giorno anche noi potremo tornare liberi.

Anche l’assegnazione qui in Norvegia del premio Nobel a me, un semplice monaco originario del lontano Tibet, riempie di speranza i tibetani. Essa significa che, nonostante non abbiamo attirato l’attenzione sulla nostra situazione per mezzo della violenza, non siamo stati dimenticati. Significa anche che i valori che abbiamo cari, in particolare il nostro rispetto per tutte le forme di vita e la fede nel potere della verità, sono oggi riconosciuti e incoraggiati. È anche un tributo al mio maestro spirituale, il Mahatma Gandhi, il cui esempio è una fonte d’ispirazione per tanti di noi. Il premio di quest’anno è un’indicazione che questo senso di responsabilità universale sta crescendo. Sono profondamente commosso dal sincero interesse mostrato da così tante persone in questa parte del mondo per le sofferenze del popolo del Tibet. Questa è una fonte di speranza non solo per noi tibetani ma anche per tutti i popoli oppressi.

Come sapete, da quarant’anni il Tibet è sotto l’occupazione straniera. Attualmente, più di duecentocinquantamila militari cinesi sono di stanza nel Tibet. Alcune fonti stimano che l’esercito di occupazione sia due volte più numeroso.

Durante questo lungo periodo, i tibetani sono stati privati dei loro diritti umani più fondamentali, compreso il diritto alla vita e alle libertà di movimento, di espressione e di culto, solo per citarne alcuni. Più di un sesto dei sei milioni della popolazione del Tibet è morto come risultato diretto dell’invasione e occupazione cinese. Ancor prima che iniziasse la Rivoluzione culturale, molti monasteri, templi ed edifici storici del Tibet furono distrutti. Quasi tutti quelli restanti sono stati distrutti durante la Rivoluzione culturale. Ma non voglio soffermarmi su questo punto, che è ben documentato, ciò che ritengo importante è rendervi conto del fatto che, malgrado la limitata libertà accordata dopo il 1979 di ricostruire parti di alcuni monasteri e altri segni di liberalizzazione di questo tipo, i diritti umani fondamentali del popolo tibetano sono tuttora sistematicamente violati e negli ultimi mesi, questa orribile situazione è persino peggiorata.

Se non fosse per la nostra comunità in esilio, così generosamente ospitata e sostenuta dal governo e dal popolo dell’India e aiutata da organizzazioni e individui di molte parti del mondo, la nostra nazione sarebbe soltanto poco più dei resti frantumati di un popolo. La nostra cultura, la nostra religione e la nostra identità nazionale sarebbero state eliminate del tutto. Come stanno le cose, abbiamo costruito scuole e monasteri in esilio e abbiamo creato istituzioni democratiche per servire il nostro popoio e conservare i semi della nostra civiltà. Con questa esperienza, intendiamo realizzare una piena democrazia in un futuro Tibet libero. Così, méntre sviluppiamo la nostra comunità in esilio su linee moderne, conserviamo anche la nostra identità e la nostra cultura e portiamo speranza a milioni di nostri connazionali che vivono nel Tibet.

Un problema che risulta di massima urgenza in questo momento è il massiccio afflusso di coloni cinesi nel Tibet. Nonostante nei primi decenni dell’occupazione un notevole numero di cinesi si sia trasferito nelle parti orientali dei Tibet — nelle provincie tibetane dell’Amdo (Chinghai) e del Kham (gran parte del quale è stata annessa dalla provincia cinese adiacente) — dal 1983 un numero senza precedenti di cinesi è stato incoraggiato dal loro governo a immigrare in tutte le parti del Tibet, compreso il Tibet centrale e occidentale (che la Repubblica popolare cinese chiama Regione autonoma dei Tibet).

I tibetani sono stati rapidamente ridotti a un’insignificante minoranza nella loro stessa patria. Questo sviluppo, che minaccia la sopravvivenza stessa della nazione tibetana, della sua cultura e della sua eredità spirituale, si può ancora arrestare e invertire. Ma bisogna farlo ora, prima che sia troppo tardi.

Il nuovo ciclo di proteste e violenta repressione, iniziato nel Tibet nel settembre del 1987 e che è culminato nell’imposizione della legge marziale nella capitale, Lhasa, nel marzo di quest’anno, è stato in gran parte una reazione a questo tremendo afflusso cinese. Le informazioni giunte a noi in esilio indicano che le marce di protesta e altre forme pacifiche di protesta stanno continuando a Lhasa e in numerosi altri luoghi in Tibet, nonostante le severe punizioni e il trattamento inumano cui sono stati sottoposti i tibetani detenuti per aver espresso le loro rimostranze. Il numero di tibetani uccisi dalle forze di polizia durante la protesta di marzo e quelli morti in detenzione in seguito non è noto, ma si ritiene che siano più di duecento. Migliaia sono stati fermati o arrestati e imprigionati, e la tortura è una pratica comune.

È sulla base di questa situazione che peggiora ogni giorno, e per impedire un ulteriore spargimento di sangue, che ho proposto quello che viene generalmente chiamato “Piano di pace in cinque punti” per il ristabilire la pace e i diritti umani in Tibet. Ho elaborato questo piano in un discorso a Strasburgo l’anno scorso. Credo che il piano rappresenti una cornice ragionevole e realistica per negoziati con la Repubblica popolare di Cina. Finora, però, i leader cinesi non sono stati disposti a rispondere in modo costruttivo. La brutale repressione del movimento democratico cinese nel giugno di quest’anno ha tuttavia rafforzato la mia opinione che qualsiasi sistemazione della questione tibetana avrà senso solo se sostenuta da adeguate garanzie internazionali.

Il Piano di pace in cinque punti affronta i principali problemi interconnessi, gli stessi problemi a cui mi riferivo nella prima parte di questo discorso.

Esso chiede:

-

la trasformazione dell’intero Tibet, comprese le province orientali del Kham e dell’Amdo, in una Zona di ahimsa (non violenza);

-

l’abbandono della politica di trasferimento della popolazione cinese;

-

il rispetto dei diritti umani fondamentali e delle libertà democratiche del popolo tibetano;

-

il ripristino e la protezione dell’ambiente naturale del Tibet; e

-

l’inizio di seri negoziati sullo status futuro del Tibet e delle relazioni tra i popoli tibetano e cinese.

Nel discorso di Strasburgo, ho proposto che il Tibet diventi un’entità politica autogovernata e democratica.

Vorrei cogliere questa occasione per spiegare il concetto di Zona di ahimsa o santuario di pace, che è l’elemento centrale del Piano in cinque punti. Sono convinto che esso sia di grande importanza non solo per il Tibet ma per la pace e la stabilità in Asia.

Il mio sogno è trasformare l’intero altopiano tibetano in un libero rifugio in cui la specie umana e la natura possano vivere in pace e in armonioso equilibrio. Un luogo in cui le persone, provenienti da tutte le parti del mondo, potrebbero andare e cercare il vero significato della pace dentro se stessi, lontano dalle tensioni e dalle pressioni presenti nella maggior parte del resto del mondo. Il Tibet potrebbe veramente diventare un centro creativo per la promozione e lo sviluppo della pace.

Questi sono gli elementi fondamentali della proposta Zona di AHIMSA:

-

L’intero altopiano tibetano sarebbe smilitarizzato.

-

La produzione, sperimentazione e stoccaggio di armi nucleari e di altri armamenti sull’altopiano tibetano sarebbero proibiti.

-

L’altopiano tibetano sarebbe trasformato nel più grande parco naturale o biosfera del mondo. Sarebbero promulgate leggi rigorose per proteggere la fauna selvatica e la flora; lo sfruttamento delle risorse naturali sarebbe accuratamente regolato in modo da non danneggiare importanti ecosistemi; nelle aree popolate, sarebbe adottata una politica di sviluppo sostenibile.

-

La produzione e l’uso dell’energia nucleare, e di altre tecnologie che producono rifiuti pericolosi sarebbero proibiti.

-

Le risorse e la politica nazionale sarebbero dirette verso l’attiva promozione della pace e della protezione dell’ambiente. Le organizzazioni dedicate al mantenimento della pace e alla protezione di tutte le forme di vita troverebbero in Tibet una patria ospitale.

-

Sarebbe incoraggiata in Tibet l’istituzione di organizzazioni internazionali e regionali per la promozione e la protezione dei diritti umani.

L’altitudine e le dimensioni del Tibet (pari a quelle della Comunità europea), assieme alla sua storia e alla sua eredità spirituale, lo rendono idealmente adatto a svolgere il ruolo di santuario di pace nel cuore strategico dell’Asia.

Sarebbe anche in armonia con il ruolo storico del Tibet come nazione buddista pacifica e regione cuscinetto tra le grandi potenze asiatiche, spesso rivali.

Per ridurre le tensioni esistenti in Asia, il presidente dell’Unione Sovietica, Michail Gorbaciov, ha proposto la smilitarizzazione della frontiera sovietico-cinese e la sua trasformazione in una “frontiera di pace e buon vicinato”. Il governo del Nepal aveva già proposto che il paese himalaiano del Nepal, confinante con il Tibet, diventasse una zona di pace, anche se questa proposta non comprendeva la smilitarizzazione del paese.

Per la stabilità e la pace dell’Asia, è essenziale creare delle zone di pace che separino le grandi potenze, e le altre potenziali avversarie.

La proposta del presidente Gorbaciov, che comprendeva anche un totale ritiro delle truppe sovietiche dalla Mongolia, contribuirebbe a ridurre la tensione e il potenziale pericolo di un confronto tra l’Unione Sovietica e la Cina. Una vera zona di pace deve evidentemente essere creata anche per separare i due Stati più popolosi del mondo, la Cina e l’india.

La creazione della Zona di AHIMSA richiederebbe il ritiro di truppe e installazioni militari dal Tibet, cosa che consentirebbe all’India e al Nepal di ritirare anch’essi truppe e installazioni militari dalle regioni himalaiane confinanti con il Tibet. Questo dovrebbe essere ottenuto mediante accordi internazionali. Sarebbe nel migliore interesse di tutti gli Stati dell’Asia, specialmente della Cina e dell’India, e accrescerebbe la loro sicurezza riducendo allo stesso tempo il peso economico di mantenere alte concentrazioni di truppe in aree remote.

Il Tibet non sarebbe la prima area strategica a essere smilitarizzata. Parti della penisola del Sinai, il territorio egiziano che separa Israele e l’Egitto, sono state smilitarizzate da qualche tempo. Il Costarica e ovviamente il miglior esempio di un paese interamente smilitarizzato.

Il Tibet non sarebbe nemmeno la prima area a essere trasformata in una riserva naturale. Molti parchi sono stati creati in tutto il mondo. Alcune aree strategiche sono state trasformate in “parchi naturali della pace”. Due esempi ne sono il parco La Amistad al confine tra Costarica e Panama e il progetto Sì a Paz sul confine tra Costarica e Nicaragua. Quando ho visitato il Costarica, agli inizi di quest’anno, ho visto come un paese può svilupparsi con successo senza un esercito, diventare una stabile democrazia dedita alla pace e alla protezione dell’ambiente naturale. Questo confermò la mia convinzione che la mia visione del Tibet nel futuro è un piano realistico, non meramente un sogno.

Consentitemi di finire con una nota personale di ringraziamento a tutti voi e ai nostri amici che non sono qui oggi. L’interesse e il sostegno che voi avete espresso per la condizione dei tibetani ci hanno grandemente commosso e continuano a darci coraggio per lottare per la libertà e la giustizia; non mediante l’uso delle armi materiali ma con le potenti armi della verità e della determinazione. So di parlare a nome di tutto il Tibet quando vi ringrazio e vi chiedo di non dimenticare il Tibet in questo momento critico nella storia del nostro paese. Anche noi speriamo di contribuire allo sviluppo di un mondo più pacifico, più umano e più bello. Un futuro Tibet libero cercherà di aiutare coloro che hanno bisogno in tutto il mondo, di proteggere la natura e di promuovere la pace. Credo che la capacità tibetana di combinare qualità spirituali con un atteggiamento realistico e pratico ci permetta di dare uno speciale contributo, sia pure in modo modesto. Questa è la mia speranza e la mia preghiera.

Per concludere, permettetemi di condividere con voi una breve preghiera che mi dona grande ispirazione e determinazione:

Finché durerà lo spazio,

e finché rimarranno degli esseri umani,

fino ad allora possa rimanere anch’io

a scacciare la sofferenza del mondo.

Vi ringrazio».

Nobel Peace Prize Acceptance Speech

Your Majesty, Members of the Nobel Committee, Brothers and Sisters.

I am very happy to be here with you today to receive the Nobel Prize for Peace. I feel honored, humbled and deeply moved that you should give this important prize to a simple monk from Tibet I am no one special. But I believe the prize is a recognition of the true value of altruism, love, compassion and non-violence which I try to practice, in accordance with the teachings of the Buddha and the great sages of India and Tibet

I accept the prize with profound gratitude on behalf of the oppressed everywhere and for all those who struggle for freedom and work for world peace. I accept it as a tribute to the man who founded the modern tradition of non-violent action for change Mahatma Gandhi whose life taught and inspired me. And, of course, I accept it on behalf of the six million Tibetan people, my brave countrymen and women inside Tibet, who have suffered and continue to suffer so much. They confront a calculated and systematic strategy aimed at the destruction of their national and cultural identities. The prize reaffirms our conviction that with truth, courage and determination as our weapons, Tibet will be liberated.

No matter what part of the world we come from, we are all basically the same human beings. We all seek happiness and try to avoid suffering. We have the same basic human needs and is concerns. All of us human beings want freedom and the right to determine our own destiny as individuals and as peoples. That is human nature. The great changes that are taking place everywhere in the world, from Eastern Europe to Africa are a clear indication of this.

In China the popular movement for democracy was crushed by brutal force in June this year. But I do not believe the demonstrations were in vain, because the spirit of freedom was rekindled among the Chinese people and China cannot escape the impact of this spirit of freedom sweeping many parts of the world. The brave students and their supporters showed the Chinese leadership and the world the human face of that great nation.

Last week a number of Tibetans were once again sentenced to prison terms of upto nineteen years at a mass show trial, possibly intended to frighten the population before today’s event. Their only ‘crime” was the expression of the widespread desire of Tibetans for the restoration of their beloved country’s independence.

The suffering of our people during the past forty years of occupation is well documented. Ours has been a long struggle. We know our cause is just Because violence can only breed more violence and suffering, our struggle must remain non-violent and free of hatred. We are trying to end the suffering of our people, not to inflict suffering upon others.

It is with this in mind that I proposed negotiations between Tibet and China on numerous occasions. In 1987, I made specific proposals in a Five-Point plan for the restoration of peace and human rights in Tibet. This included the conversion of the entire Tibetan plateau into a Zone of Ahimsa, a sanctuary of peace and non-violence where human beings and nature can live in peace and harmony.

last year, I elaborated on that plan in Strasbourg, at the European Parliament I believe the ideas I expressed on those occasions are both realistic. and reasonable although they have been criticised by some of my people as being too conciliatory. Unfortunately, China’s leaders have not responded positively to the suggestions we have made, which included important concessions. If this continues we will be compelled to reconsider our position.

Any relationship between Tibet and China will have to be based on the principle of equality, respect, trust and mutual benefit. It will also have to be based on the principle which the wise rulers of Tibet and of China laid down in a treaty as early as 823 AD, carved on the pillar which still stands today in front of the Jokhang, Tibet’s holiest shrine, in Lhasa, that “Tibetans will live happily in the great land of Tibet, and the Chinese will live happily in the great land of China”.

As a Buddhist monk, my concern extends to all members of the human family and, indeed, to all sentient beings who suffer. I believe all suffering is caused by ignorance. People inflict pain on others in the selfish pursuit of their happiness or satisfaction. Yet true happiness comes from a sense of brotherhood and sisterhood. We need to cultivate a universal responsibility for one another and the planet we share. Although I have found my own Buddhist religion helpful in generating love and com passion, even for those we consider our enemies, I am convinced that everyone can develop a good heart and a sense of universal responsibility with or without religion.

With the ever growing impact of science on our lives, religion and spirituality have a greater role to play reminding us of our humanity. There is no contradiction between the two. Each gives us valuable insights into the other. Both science and the teachings of the Buddha tell us of the fundamental unity of all things. This understanding is crucial if we are to take positive and decisive action on the pressing global concern with the environment.

I believe all religions pursue the same goals, that of cultivating human goodness and bringing happiness to all human beings. Though the means might appear different the ends are the same.

As we enter the final decade of this century I am optimistic that the ancient values that have sustained mankind are today reaffirming themselves to prepare us for a kinder, happier twenty-first century.

I pray for all of us, oppressor and friend, that together we succeed in building a better world through human under-standing and love, and that in doing so we may reduce the pain and suffering of all sentient beings.

Thank you.

University Aula, Oslo, 10 December 1989http://www.dalailama.com/messages/acceptance-speeches/nobel-peace-prize

Nobel Lecture

It is an honour and pleasure to be among you today. I am really happy to see so many old friends who have come from different corners of the world, and to make new friends, whom I hope to meet again in the future. When I meet people in different parts of the world, I am always reminded that we are all basically alike: we are all human beings. Maybe we have different clothes, our skin is of a different colour, or we speak different languages. That is on the surface. But basically, we are the same human beings. That is what binds us to each other. That is what makes it possible for us to understand each other and to develop friendship and closeness.

Thinking over what I might say today, I decided to share with you some of my thoughts concerning the common problems all of us face as members of the human family. Because we all share this small planet earth, we have to learn to live in harmony and peace with each other and with nature. That is not just a dream, but a necessity. We are dependent on each other in so many ways, that we can no longer live in isolated communities and ignore what is happening outside those communities, and we must share the good fortune that we enjoy. I speak to you as just another human being; as a simple monk. If you find what I say useful, then I hope you will try to practise it.

I also wish to share with you today my feelings concerning the plight and aspirations of the people of Tibet. The Nobel Prize is a prize they well deserve for their courage and unfailing determination during the past forty years of foreign occupation. As a free spokesman for my captive countrymen and -women, I feel it is my duty to speak out on their behalf. I speak not with a feeling of anger or hatred towards those who are responsible for the immense suffering of our people and the destruction of our land, homes and culture. They too are human beings who struggle to find happiness and deserve our compassion. I speak to inform you of the sad situation in my country today and of the aspirations of my people, because in our struggle for freedom, truth is the only weapon we possess.

The realisation that we are all basically the same human beings, who seek happiness and try to avoid suffering, is very helpful in developing a sense of brotherhood and sisterhood; a warm feeling of love and compassion for others. This, in turn, is essential if we are to survive in this ever shrinking world we live in. For if we each selfishly pursue only what we believe to be in our own interest, without caring about the needs of others, we not only may end up harming others but also ourselves. This fact has become very clear during the course of this century. We know that to wage a nuclear war today, for example, would be a form of suicide; or that by polluting the air or the oceans, in order to achieve some short-term benefit, we are destroying the very basis for our survival. As interdependents, therefore, we have no other choice than to develop what I call a sense of universal responsibility.

Today, we are truly a global family. What happens in one part of the world may affect us all. This, of course, is not only true of the negative things that happen, but is equally valid for the positive developments. We not only know what happens elsewhere, thanks to the extraordinary modern communications technology. We are also directly affected by events that occur far away. We feel a sense of sadness when children are starving in Eastern Africa. Similarly, we feel a sense of joy when a family is reunited after decades of separation by the Berlin Wall. Our crops and livestock are contaminated and our health and livelihood threatened when a nuclear accident happens miles away in another country. Our own security is enhanced when peace breaks out between warring parties in other continents.

But war or peace; the destruction or the protection of nature; the violation or promotion of human rights and democratic freedoms; poverty or material well-being; the lack of moral and spiritual values or their existence and development; and the breakdown or development of human understanding, are not isolated phenomena that can be analysed and tackled independently of one another. In fact, they are very much interrelated at all levels and need to be approached with that understanding.

Peace, in the sense of the absence of war, is of little value to someone who is dying of hunger or cold. It will not remove the pain of torture inflicted on a prisoner of conscience. It does not comfort those who have lost their loved ones in floods caused by senseless deforestation in a neighbouring country. Peace can only last where human rights are respected, where the people are fed, and where individuals and nations are free. True peace with oneself and with the world around us can only be achieved through the development of mental peace. The other phenomena mentioned above are similarly interrelated. Thus, for example, we see that a clean environment, wealth or democracy mean little in the face of war, especially nuclear war, and that material development is not sufficient to ensure human happiness.

Material progress is of course important for human advancement. In Tibet, we paid much too little attention to technological and economic development, and today we realise that this was a mistake. At the same time, material development without spiritual development can also cause serious problems, In some countries too much attention is paid to external things and very little importance is given to inner development. I believe both are important and must be developed side by side so as to achieve a good balance between them. Tibetans are always described by foreign visitors as being a happy, jovial people. This is part of our national character, formed by cultural and religious values that stress the importance of mental peace through the generation of love and kindness to all other living sentient beings, both human and animal. Inner peace is the key: if you have inner peace, the external problems do not affect your deep sense of peace and tranquility. In that state of mind you can deal with situations with calmness and reason, while keeping your inner happiness. That is very important. Without this inner peace, no matter how comfortable your life is materially, you may still be worried, disturbed or unhappy because of circumstances.

Clearly, it is of great importance, therefore, to understand the interrelationship among these and other phenomena, and to approach and attempt to solve problems in a balanced way that takes these different aspects into consideration. Of course it is not easy. But it is of little benefit to try to solve one problem if doing so creates an equally serious new one. So really we have no alternative: we must develop a sense of universal responsibility not only in the geographic sense, but also in respect to the different issues that confront our planet.

Responsibility does not only lie with the leaders of our countries or with those who have been appointed or elected to do a particular job. It lies with each one of us individually. Peace, for example, starts with each one of us. When we have inner peace, we can be at peace with those around us. When our community is in a state of peace, it can share that peace with neighbouring communities, and so on. When we feel love and kindness towards others, it not only makes others feel loved and cared for, but it helps us also to develop inner happiness and peace. And there are ways in which we can consciously work to develop feelings of love and kindness. For some of us, the most effective way to do so is through religious practice. For others it may be non-religious practices. What is important is that we each make a sincere effort to take our responsibility for each other and for the natural environment we live in seriously.

I am very encouraged by the developments which are taking place around us. After the young people of many countries, particularly in northern Europe, have repeatedly called for an end to the dangerous destruction of the environment which was being conducted in the name of economic development, the world’s political leaders are now starting to take meaningful steps to address this problem. The report to the United Nations Secretary-General by the World Commission on the Environment and Development (the Brundtland Report) was an important step in educating governments on the urgency of the issue. Serious efforts to bring peace to war-torn zones and to implement the right to self-determination of some people have resulted in the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan and the establishment of independent Namibia. Through persistent nonviolent popular efforts dramatic changes, bringing many countries closer to real democracy, have occurred in many places, from Manila in the Philippines to Berlin in East Germany. With the Cold War era apparently drawing to a close, people everywhere live with renewed hope. Sadly, the courageous efforts of the Chinese people to bring similar change to their country was brutally crushed last June. But their efforts too are a source of hope. The military might has not extinguished the desire for freedom and the determination of the Chinese people to achieve it. I particularly admire the fact that these young people who have been taught that “power grows from the barrel of the gun”, chose, instead, to use nonviolence as their weapon.

What these positive changes indicate, is that reason, courage, determination, and the inextinguishable desire for freedom can ultimately win. In the struggle between forces of war, violence and oppression on the one hand, and peace, reason and freedom on the other, the latter are gaining the upper hand. This realisation fills us Tibetans with hope that some day we too will once again be free.

The awarding of the Nobel Prize to me, a simple monk from faraway Tibet, here in Norway, also fills us Tibetans with hope. It means, despite the fact that we have not drawn attention to our plight by means of violence, we have not been forgotten. It also means that the values we cherish, in particular our respect for all forms of life and the belief in the power of truth, are today recognised and encouraged. It is also a tribute to my mentor, Mahatma Gandhi, whose example is an inspiration to so many of us. This year’s award is an indication that this sense of universal responsibility is developing. I am deeply touched by the sincere concern shown by so many people in this part of the world for the suffering of the people of Tibet. That is a source of hope not only for us Tibetans, but for all oppressed people.

As you know, Tibet has, for forty years, been under foreign occupation. Today, more than a quarter of a million Chinese troops are stationed in Tibet. Some sources estimate the occupation army to be twice this strength. During this time, Tibetans have been deprived of their most basic human rights, including the right to life, movement, speech, worship, only to mention a few. More than one sixth of Tibet’s population of six million died as a direct result of the Chinese invasion and occupation. Even before the Cultural Revolution started, many of Tibet’s monasteries, temples and historic buildings were destroyed. Almost everything that remained was destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. I do not wish to dwell on this point, which is well documented. What is important to realise, however, is that despite the limited freedom granted after 1979, to rebuild parts of some monasteries and other such tokens of liberalisation, the fundamental human rights of the Tibetan people are still today being systematically violated. In recent months this bad situation has become even worse.

If it were not for our community in exile, so generously sheltered and supported by the government and people of India and helped by organisations and individuals from many parts of the world, our nation would today be little more than a shattered remnant of a people. Our culture, religion and national identity would have been effectively eliminated. As it is, we have built schools and monasteries in exile and have created democratic institutions to serve our people and preserve the seeds of our civilisation. With this experience, we intend to implement full democracy in a future free Tibet. Thus, as we develop our community in exile on modern lines, we also cherish and preserve our own identity and culture and bring hope to millions of our countrymen and -women in Tibet.

The issue of most urgent concern at this time, is the massive influx of Chinese settlers into Tibet. Although in the first decades of occupation a considerable number of Chinese were transferred into the eastern parts of Tibet – in the Tibetan provinces of Amdo (Chinghai) and Kham (most of which has been annexed by neighboring Chinese provinces) – since 1983 an unprecedented number of Chinese have been encouraged by their government to migrate to all parts of Tibet, including central and western Tibet (which the People’s Republic of China refers to as the so-called Tibet Autonomous Region). Tibetans are rapidly being reduced to an insignificant minority in their own country. This development, which threatens the very survival of the Tibetan nation, its culture and spiritual heritage, can still be stopped and reversed. But this must be done now, before it is too late.

The new cycle of protest and violent repression, which started in Tibet in September of 1987 and culminated in the imposition of martial law in the capital, Lhasa, in March of this year, was in large part a reaction to this tremendous Chinese influx. Information reaching us in exile indicates that the protest marches and other peaceful forms of protest are continuing in Lhasa and a number of other places in Tibet, despite the severe punishment and inhumane treatment given to Tibetans detained for expressing their grievances. The number of Tibetans killed by security forces during the protest in March and of those who died in detention afterwards is not known but is believed to be more than two hundred. Thousands have been detained or arrested and imprisoned, and torture is commonplace.

It was against the background of this worsening situation and in order to prevent further bloodshed, that I proposed what is generally referred to as the Five-Point Peace Plan for the restoration of peace and human rights in Tibet. I elaborated on the plan in a speech in Strasbourg last year. I believe the plan provides a reasonable and realistic framework for negotiations with the People’s Republic of China. So far, however, China’s leaders have been unwilling to respond constructively. The brutal suppression of the Chinese democracy movement in June of this year, however, reinforced my view that any settlement of the Tibetan question will only be meaningful if it is supported by adequate international guarantees.

The Five-Point Peace Plan addresses the principal and interrelated issues, which I referred to in the first part of this lecture. It calls for (1) Transformation of the whole of Tibet, including the eastern provinces of Kham and Amdo, into a zone of Ahimsa (nonviolence); (2) Abandonment of China’s population transfer policy; (3) Respect for the Tibetan people’s fundamental rights and democratic freedoms; (4) Restoration and protection of Tibet’s natural environment; and (5) Commencement of earnest negotiations on the future status of Tibet and of relations between the Tibetan and Chinese people. In the Strasbourg address I proposed that Tibet become a fully self-governing democratic political entity.

I would like to take this opportunity to explain the Zone of Ahimsa or peace sanctuary concept, which is the central element of the Five-Point Peace Plan. I am convinced that it is of great importance not only for Tibet, but for peace and stability in Asia.

It is my dream that the entire Tibetan plateau should become a free refuge where humanity and nature can live in peace and in harmonious balance. It would be a place where people from all over the world could come to seek the true meaning of peace within themselves, away from the tensions and pressures of much of the rest of the world. Tibet could indeed become a creative center for the promotion and development of peace.

The following are key elements of the proposed Zone of Ahimsa:

-

the entire Tibetan plateau would be demilitarised;

-

the manufacture, testing, and stockpiling of nuclear weapons and other armaments on the Tibetan plateau would be prohibited;

-

the Tibetan plateau would be transformed into the world’s largest natural park or biosphere. Strict laws would be enforced to protect wildlife and plant life; the exploitation of natural resources would be carefully regulated so as not to damage relevant ecosystems; and a policy of sustainable development would be adopted in populated areas;

-

the manufacture and use of nuclear power and other technologies which produce hazardous waste would be prohibited;

-

national resources and policy would be directed towards the active promotion of peace and environmental protection. Organisations dedicated to the furtherance of peace and to the protection of all forms of life would find a hospitable home in Tibet;

-

the establishment of international and regional organisations for the promotion and protection of human rights would be encouraged in Tibet.

Tibet’s height and size (the size of the European Community), as well as its unique history and profound spiritual heritage makes it ideally suited to fulfill the role of a sanctuary of peace in the strategic heart of Asia. It would also be in keeping with Tibet’s historical role as a peaceful Buddhist nation and buffer region separating the Asian continent’s great and often rival powers.

In order to reduce existing tensions in Asia, the President of the Soviet Union, Mr. Gorbachev, proposed the demilitarisation of Soviet-Chinese borders and their transformation into “a frontier of peace and good-neighborliness”. The Nepal government had earlier proposed that the Himalayan country of Nepal, bordering on Tibet, should become a zone of peace, although that proposal did not include demilitarisation of the country.

For the stability and peace of Asia, it is essential to create peace zones to separate the continent’s biggest powers and potential adversaries. President Gorbachev’s proposal, which also included a complete Soviet troop withdrawal from Mongolia, would help to reduce tension and the potential for confrontation between the Soviet Union and China. A true peace zone must, clearly, also be created to separate the world’s two most populous states, China and India.

The establishment of the Zone of Ahimsa would require the withdrawal of troops and military installations from Tibet, which would enable India and Nepal also to withdraw troops and military installations from the Himalayan regions bordering Tibet. This would have to be achieved by international agreements. It would be in the best interest of all states in Asia, particularly China and India, as it would enhance their security, while reducing the economic burden of maintaining high troop concentrations in remote areas.

Tibet would not be the first strategic area to be demilitarised. Parts of the Sinai peninsula, the Egyptian territory separating Israel and Egypt, have been demilitarised for some time. Of course, Costa Rica is the best example of an entirely demilitarised country. Tibet would also not be the first area to be turned into a natural preserve or biosphere. Many parks have been created throughout the world. Some very strategic areas have been turned into natural “peace parks”. Two examples are the La Amistad Park, on the Costa Rica-Panama border and the Si A Paz project on the Costa Rica-Nicaragua border.

When I visited Costa Rica earlier this year, I saw how a country can develop successfully without an army, to become a stable democracy committed to peace and the protection of the natural environment. This confirmed my belief that my vision of Tibet in the future is a realistic plan, not merely a dream.

Let me end with a personal note of thanks to all of you and our friends who are not here today. The concern and support which you have expressed for the plight of the Tibetans have touched us all greatly, and continue to give us courage to struggle for freedom and justice: not through the use of arms, but with the powerful weapons of truth and determination. I know that I speak on behalf of all the people of Tibet when I thank you and ask you not to forget Tibet at this critical time in our country’s history. We too hope to contribute to the development of a more peaceful, more humane and more beautiful world. A future free Tibet will seek to help those in need throughout the world, to protect nature, and to promote peace. I believe that our Tibetan ability to combine spiritual qualities with a realistic and practical attitude enables us to make a special contribution, in however modest a way. This is my hope and prayer.

In conclusion, let me share with you a short prayer which gives me great inspiration and determination:

For as long as space endures,

And for as long as living beings remain,

Until then may I, too, abide

To dispel the misery of the world.

Thank you.

Nobel Lecture, December 11, 1989

http://www.dalailama.com/messages/acceptance-speeches/nobel-peace-prize/nobel-lecture