His Holiness the Dalai Lama: When one is actually cultivating tranquil abiding one needs to choose an object of meditation.

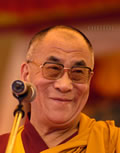

A Commentary on “A Lamp for the Path”

by His Holiness the Dalai Lama

Translated by Thubten Jinpa

Melbourne, Australia

May 19-22, 2002

Day three

Yesterday I spoke about how bodhicitta is the essence of the practice, the core practice. The cultivation of bodhicitta requires its undertaking through successive lifetimes. So although one’s ultimate object of aspiration is the attainment of definite goodness particularly the fully enlightened state of Buddhahood but although this is the final goal in order to achieve this aim one needs to go through successive life forms suitable for undertaking this practice without interruption. Gaining appropriate life forms means to be born as a human or the higher realms of existence. It is necessary therefore to seek the conditions and causes for insuring the continual attainment of higher realms, birth in the higher realms [high status] so that one can carry on with the practices that eventually culminate in the attainment of Buddhahood.

One can summarize all of the aspects of practice in the following manner. All of the practices that are related to the achievement of birth in the higher realms belong to the class of the initial scope. All of the practices that are related to the attainment of liberation from cyclic existence and the elimination of the defilements of the afflictions belong to the practices of the middling scope. All of the practices that are specifically related to the means of attaining the omniscient state of Buddhahood belong to those of supreme capacity or the higher scope.

As I explained before the main objective of the practitioner of this particular text, the Lamp for the Path are those who seek the attainment of full enlightenment of Buddhahood. So the practices that are explained as part of the initial scope and the middling scope are in fact prerequisites or common aspects of the path.

Verse three in the text reads:

Know that those who by whatever means

3 Seek for themselves no more

The pleasures of cyclic existence

Are persons of the least capacity.

The main point of this verse has already been explained. This refers to the practitioners of the initial scope where the primary objective is to seek the means of attaining birth in the higher realms.

What are the means for attaining birth in the higher realms that is the spiritual objective for those of the initial scope? I touched upon this yesterday. Here the key practice is living one’s life according to the ethical discipline of refraining from the ten negative actions of body, speech and mind. These negative actions of body, speech and mind are the principal causes that lead an individual to take birth in the lower realms of existence and undergo the sufferings of those realms. Therefore by consciously and deliberately adopting an ethical discipline, refraining from these negative actions constitutes establishing the method or means by which one attains freedom from rebirth in the lower realms of existence.

What are these ten negative actions that one needs to refrain from? There are three actions of body, taking life or killing, stealing and sexual misconduct. There are four verbal actions, telling lies, divisive speech, harsh words and engaging in gossip or frivolous speech. There are three mental actions, covetousness, ill-will or harmful intent and harboring wrong views.

It is by living according to the ethical discipline of refraining from the ten negative actions that one seeks freedom from birth in the lower realms of existence. Therefore the practices that are involved for the initial scope are primarily of two categories. One category of the practice is to engage in the training of mind so that one cultivates the genuine aspiration or wish to gain freedom from the lower realms of existence. The second category is to then cultivate the means by which one can achieve this aim. The means here refers to cultivating the understanding of the laws of cause and effect, particularly that of karma and then living according to the law of karma by abstaining from the negative actions of body, speech and mind.

This is in fact the precept that one takes as the result of taking refuge in the Three Jewels because without having some understanding of the nature of the Three Jewels one will not be able to appreciate the important aspect of the law of karma. Therefore in this practice one needs both going for refuge and then living out the precepts of refuge which is to live according to the principal of karma, the law of cause and effect. So one needs to cultivate conviction in the law of karma and also go for refuge. In order to do this one must first cultivate a genuine desire to seek freedom from rebirth in the lower realms of existence. In order to do this one must first develop some understanding of the intensity of the suffering in the lower realms. This is done by reflecting upon the suffering of the lower realms and also appreciating the transient nature of one’s life.

In order to fully appreciate the importance of gaining a favorable rebirth through engaging in the practice one must first appreciate the preciousness of the opportunities that one has right now as a human being. Therefore it is important to realize the value of human life and also the opportunities a human existence provides for one. So in this way one can see how all of these various elements of the practices are part of the spiritual practices of the initial scope. One has recognition of the preciousness of human existence, the opportunities accorded to one by such a birth, understanding the sufferings of the lower realms of existence, going for refuge, developing conviction in the laws of cause and effect and understanding the transient nature of life. One can see that all of these are interrelated and constitute the practices of the initial scope.

Some Tibetan masters have said that when reflecting upon the value of human existence and its preciousness that it is important for spiritual practitioners to insure that the human life one now has becomes truly precious so that it becomes of source of jewels, something that leads to goodness. It is important to insure that one’s human life does not become the source of one’s own downfall, something that brings ruin and disaster to oneself.

What is involved here by engaging in these practices is in fact that one is engaged in a process of training the mind. It is through engaging in the training of the mind, through disciplining one’s mind that one is trying to bring about transformation not only at the mental level but also that of one’s bodily actions. So starting from the practices of the initial scope which involve adopting the ethical discipline of refraining from the ten negative actions, what one is doing is not living an ethical discipline which is imposed from outside oneself according to the law or dictates but rather it is a discipline that is voluntarily embraced on the understanding of its value. One embraces this discipline for oneself so it is a form of self-discipline that one embraces for oneself. It is through this process that one can expect to effect change. If the discipline is externally imposed according to the authority of some body such as a court or law then its impact on one’s mental training may not be very effective.

In order for discipline to be effective it has to be voluntarily embraced and it has to be a self-discipline where the discipline is adopted on the basis of fully understanding its value. Therefore in order to develop this full understanding one needs to listen to someone who has this insight, this understanding. Therefore in Buddhism when one related to the Buddha Shakyamuni, one relates to the Buddha as a teacher. One refers to the Buddha as the teacher. For us Buddhists our relation to the Buddha Shakyamuni is not like relating to a creator, an all-powerful creator. Rather we do not expect the Buddha to have power over our destinies but rather we relate to him as a teacher. In fact Buddha himself has stated in the Sutras that oneself is one’s own master and oneself is one’s own enemy. One’s own future destiny lies in one’s own hands.

One can say that in order to develop a proper understanding of the practices one needs to rely on a teacher who is qualified in that they represent a tradition that stems from the historical Buddha Shakyamuni. So one can say that there is an uninterrupted lineage, custom or tradition has been maintained uninterrupted and a qualified teacher is someone who has inherited that body of knowledge, that body of insight. Therefore since the success of one’s practice depends upon learning it from a qualified teacher one finds that the role of the teacher is taken to be very important in the Buddhist practices. To emphasize this point one finds even in the scriptures that all of the very detailed qualifications of a teacher are mentioned starting with the Vinaya teachers up to teachers of the highest levels of the Vajrayana like Guhyasamaja or Kalachakra. All of this shows the importance of the teacher as well as the importance of one’s teacher having the qualifications. Otherwise if the teacher does not possess these qualifications as described in the scriptures there is the danger that the students may be let down.

Now in the context of Lam Rim or the Stages of the Path practices, which is the main theme of text I am discussing, the qualifications that are required on the part of the teacher are mentioned in Asanga’s Ornament of Mahayana Scriptures. There he lists ten such qualifications, the teacher must possess realizations of the three higher trainings (morality, concentration and wisdom), must be industrious in their dedication to living the ethical discipline, must have vast knowledge of scriptures, a realization of emptiness as described in the Ornament of Mahayana Scriptures as the selflessness of phenomena or at least a deep understanding of no-self, must be eloquent and skillful in speech, must possess compassion and finally the teacher must be resilient in that they do not feel demoralized or fatigued when teaching. These are the principal qualities that one needs to seek in a teacher of Lam Rim.

When discussing these qualifications of the teacher in his Great Exposition on the Stages of the Path, Tsongkapa makes a very concluding statement where he says that for someone who has failed to attain or discipline their own mind, since it is impossible for someone who has not tamed their own mind to train and discipline someone else’s mind, therefore those who wish to act as teachers must first discipline their own mind. When speaking about the method for disciplining one’s own mind it is not adequate simply to have one or two partial realizations but rather the method for disciplining one’s mind should conform to the overall teachings of the Buddha. Tsongkapa explains the overall teachings of the Buddha within the framework of the three higher trainings. In other words the teacher must have both understanding and realizations of morality, concentration and wisdom.

If however after having found a qualified teacher, even though the teacher may be fully qualified in certain areas if one finds the instruction given to one are contrary to or in conflict with the overall teachings of the Buddha then it is stated in the Vinaya, the monastic discipline one must reject it. Similarly one finds in the scriptures, sutras quoted by Tsongkapa in his Great Exposition that those instructions that conform to the general ethical norms must be followed. However those instructions that do not conform to general ethical norms must not be practiced. In the case of the Vajrayana one finds in the Fifty Verses on the Guru that it is explained that if an instruction given to one by one’s teacher one is either incapable of fulfilling that advice or if one understands that by following that advice one will cause harm then one needs to use common sense. One needs to explain to one’s teacher the reason why one cannot implement the advice they have given. So these points are actually mentioned in the scriptures themselves.

[24. The wise should strive to listen to what the guru orders with a happy mind. If one is not reasonably able to do it, explain that one is unable.]

Fifty Stanzas on the Guru

There is a tradition in Tibet where a tremendous emphasis is placed on the authenticity of the lineage of one’s teachings. In fact there is a saying that the source of pure water must be able to be traced to its source in pure snow-covered mountains. In the same manner the source of an authentic Buddhist teaching must be able to be traced the Buddha, the teacher. This I feel is very important. Whenever one engages in Buddhist practices, particularly those who consider themselves followers of the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, it is important to insure that one’s practice is authentic so that it is traceable through an authentic lineage of transmission.

Sometimes there is a danger that when one isolates practices from their authentic roots then it can become very difficult to differentiate what is genuine Buddhist practice and what is not. In fact these days there is a tendency because of the so-called New Age phenomena to takes pieces from here and there making up one’s own amalgamation or mixture of practices. This may be fine but if one is following a particular spiritual tradition like Buddhism, particularly Tibetan Buddhism then it is important to insure the purity of the lineage, that there is an authentic source for one’s practices. One does this by insuring that one’s understanding of the teachings truly conforms to the broad framework that is laid out in the writings of the great Nalanda masters. This is so one’s understanding and practice conforms to the traditions that have been established in Nalanda.

Of course among the scriptures generally speaking one can say that there are two principal types of scriptures. A teacher from Kham who had tremendous admiration for all four schools of Tibetan Buddhism although he himself was a Gelugpa, made a distinction that I think is quite relevant. He made distinctions among the scriptures by two principal types. On the one hand are those scriptures that make a general presentation within the overall framework of the Buddha’s teachings such as the writings of the Nalanda masters. There is then the other category of the teachings, which are much more specific teachings in a specialized context. These include such as the Dohas or the Experiential Songs of Saraha which are very specific instructions written by a teacher for a specific individual. Sometimes one finds spontaneous experiential songs given in very specific contexts and circumstances. These are meant for very specialized circumstances where for the purpose of an individual the text was written. These are for practitioners who already have the basic understanding of the overall framework of the Buddhist path. Other factors and conditions came into play so that a particular teaching had a special resonance and effectiveness.

These are analogous to for example in the Vinaya during the time of the Buddha it is said that there was one particular type of ritual where the candidate was so ready that he didn’t need to go through the elaborate ritual of the ordination ceremony. The Buddha simply said, “Come over here” and that constituted the actual ceremony of ordination. There is also a story in Tibet of a lama who was requested by a disciple for a specific instruction and the lama was in a hurry and said, “Go away!” In fact the student was so ready that he felt this admonition to represent a profound instruction and is said to have led to his realization. These are very individualized circumstances and therefore it is important to know that one cannot universalize from these types of specific types of instructions meant for specific contexts into an overall understanding of the Buddhist path.

There is another example. There is the story of a great Dzogchen master from Kham known as Khenpo Nisan (SP?) who is no longer alive. However I heard from one of his students that a student from Lhasa went to Kham to see the master. He felt tremendous devotion to this master just from hearing about him. When he actually met this master in person the master was reading from a text. As the student approached and prostrated to him, he was so moved that he cried. He felt tremendous devotion and deep connectedness with the master. When the teacher finished his reading the student approached and asked him to give him an instruction. The master said there was no need as he had already received it. The point is that because the student was so ready the simple encounter alone was adequate to give rise to a realization.

These show that when all of the conditions are present then a simple incident can trigger a realization. On the other hand if the conditions are not present then even if one attends a Kalachakra Initiation which lasts several days hardly anything will happen. The point I am making is that it is very important for one to develop one’s understanding of the teachings on the basis of the texts written from a general framework of the Buddhist path. If one has this kind of deeper understanding of the overall aspects of the path then one will be in a position to understand the profundity of those texts that are written for specific circumstances.

It is not so much the general presentation but the presentation made within the context of an overall understanding of the Buddhist path. It is important to develop this kind of understanding so that one will then be able to appreciate the significance and meaning of those texts that written for more specialized contexts. Whereas if one lacks the first kind of understanding which is grounded in an overall understanding of the Buddhist path then there is a danger of misunderstanding if one approaches texts that are written for specialized contexts.

Another example I can give you is that in the Tibetan tradition there is a recognition of the Six Yogas of Naropa as representing a very profound instruction or practice. Lama Tsongkapa had written a separate commentary or guide to the practices of the Six Yogas of Naropa and praised this practice tremendously. However if the practitioner of this profound instruction, the Six Yogas of Naropa lacks the kind of understanding that I have spoken about concerning the overall framework of the Buddhist path then it is very difficult to conceive how such an individual could gain benefit from the profundity of these instructions.

In themselves many of these practices of the Six Yogas are common with non-Buddhist schools as well. If one looks at the teachings of non-Buddhist schools one will find the practices of transferring consciousness or phowa, the inner heat practice as well as vase breathing. There are also many techniques for bringing about the flow of the prana, energies and drops within one’s channels. One also finds various techniques for the practices of dream yoga. Many of these can be found in the non-Buddhist practices so there is nothing uniquely Buddhist about these practices.

However if the practitioner of the Six Yogas grounds their practice in the deeper understanding of the overall framework of the Buddhist path then of course one will be able to really benefit from the profoundness of these instructions.

As for the specific explanations of topics of the Lam Rim practices such as the recognition of the preciousness of human existence, understanding the transient nature of existence and so on I shall not go into these in detail as of these can be studied from the many books that are available.

To read from the text:

Those who seek these for themselves alone

-

Turning away from worldly pleasures,

And avoiding destructive actions

Are said to be of the middling capacity.

Destructive actions here does not refer to unwholesome actions in the sense of negative karma but rather destructive actions refers to the origin of suffering which is karma and the afflictive emotions and thoughts, especially the afflictions. Therefore those spiritual practitioners who aspire to gain freedom from these afflictions are practitioners of middling capacity. The means by which they turn away from these afflictions is by eliminating them.

As for the various elements of the practices that are associated with the practitioners of middling capacity, broadly speaking they fall into two categories. One category is the training of mind to cultivate the genuine wish or desire to gain freedom, thus cultivating renunciation. The second category of practices is the cultivation of the path that brings about the fulfillment of that wish. In order to train one’s mind to cultivate a genuine desire to gain freedom from cyclic existence, one needs to reflect upon the defects of cyclic existence and also one needs to develop an understanding of the causation that exists between karma and the afflictions. So it is through these reflections, cultivating the wish to gain freedom and then embarking on the path to gain that freedom.

One finds that in the practices associated with the middling scope when describing the path that is key for bringing about the liberation that one is seeking, these practices are embodied in the Four Noble Truths. The First Noble Truth is the Truth of Suffering and when teaching the truth of suffering Buddha taught in terms of four characteristics of suffering. First is impermanence so that one finds here a contemplation on the impermanent to be an important part of the practice. One also found earlier in the context of the initial scope the importance of reflecting upon impermanence. However these two reflections on impermanence are different. In the context of the initial scope impermanence is understood more in terms of the transient nature of life and this impermanence is understood more at a gross level as the possibility of the cessation of a continuum at a certain point.

Whereas in the context of the reflection of impermanence associated with the Four Noble Truths, impermanence is much subtler and refers to the dynamic nature of reality where everything, all things and events go through momentary change, moment-by-moment change in a dynamic process. Nothing is stable. It is this understanding of subtle impermanence which then leads to an understanding of the unsatisfactoriness or suffering of cyclic existence. One can then on to an understanding of no-self or selfness. This interrelatedness of gaining insight from impermanence to suffering and then to selflessness is explained in various texts such as Aryadeva’s Four Hundred Verses. Also in Dharmakirti’s Pramanavarttika, the Exposition of Valid Cognition he explains how the insight into the former (impermanence) leads to insight into suffering and the later into no-self.

How is one to understand this subtle impermanence? If one observes the world of phenomena around one whether it is a tree or a mountain, one feels as if there is no change happening. They appear to be enduring. However over time, years or more, or in some cases thousands of years even these seemingly enduring objects change. The fact that they change is something that one can observe with one’s own eyes. In order to explain and account for this perceptible change one needs to accept that the process of change must be occurring on a moment-by-moment basis. If things did not go through change on a moment-by-moment basis then there simply would be no basis for accounting for the fact that over time one detects a perceptible change. On this basis one can say that anything that can be perceived as having changeable qualities is subject to a process of change on a moment-by-moment basis.

The question arises, what brings about this change? What is it that makes something come to the point of ceasing? Do things and events require a secondary condition to bring about their cessation? Or do things go through the process of cessation naturally? Here one can say it is not the case that things first come into being and then a secondary factor comes into play bringing about their cessation. In fact the very cause that brought about the object in question also brings about or is the very cause bringing about the cessation of that object. All things and events come into being with the “seed” for their cessation inherent within them.

Therefore all things and events are under the power of their causes and conditions so in a sense they are “other-powered”, governed by their conditions. In the context of one’s own conditioned existence since one’s own existence is also subject to the same nature of change then one’s existence is governed by causes and conditions.

In the context of one’s conditioned existence, what are these causes and conditions? Causes here refer to karma and the afflictive emotions and thoughts particularly among the afflictions the root is fundamental ignorance, the fundamental ignorance grasping at things as inherently existent. If this is so then one can understand that one’s very conditioned existence is under the power of this delusion, this affliction of ignorance. Even the very name ignorance suggests something wrong with it and distorted. So long as one remains under the power of such a force how could there ever be room for lasting goodness? Through this way one will then be able to gain insight into the unsatisfactory nature of one’s conditioned existence.

One can also understand this statement of how insight into impermanence can lead into insight of suffering and how insight into suffering can lead to insight into no-self or anatman in the following way. Once one realizes that one’s own very conditioned existence is under the power of afflictive forces such as fundamental ignorance then one will also realize that it is only by generating insight into no-self that is the direct opposite of fundamental ignorance that one will be able to dispel and eliminate this ignorance from within one. Therefore one then develops the conviction for the necessity of generating insight into the wisdom of no-self. Otherwise one may get the impression that this whole discussion of emptiness and no-self is so complex that what is its point? What is the point in engaging in such complex processes? But once one realizes that it is fundamental ignorance that binds one to one’s conditioned existence …

I can tell you a story. If one doesn’t fully understand the importance of how it is by generating wisdom into emptiness, into no-self that one can bring about the elimination of this fundamental ignorance that binds one to one’s conditioned existence one will not appreciate this point. One may wonder what is the whole point of engaging in this complex process of trying to understand emptiness, which is so difficult and so complex. Once I gave an exposition on Nagarjuna’s Fundamentals of the Middle Way, which is basically on the topic of emptiness. One of the students who did not have a prior background of learning in the great treatises made a comment to another colleague. He said today’s session was a little strange because His Holiness began with a presentation of the Buddha’s path building up an edifice one layer at a time. Then all of a sudden he started talking about emptiness and the absence of inherent existence so that the whole edifice that he spent so much time building was then completely dismantled. He couldn’t see the point. So there is this danger however if one understands the importance of the need to generate wisdom into emptiness, the means for bringing about the cessation of the afflictions particularly fundamental ignorance then one will recognize the value of deepening one’s understanding of emptiness. Also as Dharmakirti pointed out in his Exposition of Valid Cognitions that emotions like loving-kindness and compassion cannot directly challenge fundamental ignorance. It is only by cultivating the insight into no-self that one will be directly able to counter fundamental ignorance.

Having explained the various aspects of the training of mind to cultivate a genuine wish for liberation from cyclic existence, then the actual path, the means by which one brings about this freedom is explained within the framework of the three higher trainings.

The text reads:

Those who through their personal suffering

-

Truly want to end completely

All of the sufferings of others

Are persons of supreme capacity.

This refers to the practitioners of the great scope where by taking their own personal experience of suffering as an example, as a basis then they extend this understanding of suffering to other sentient beings. They recognize the fundamental equality of oneself and others so as far as the desire for overcoming suffering is concerned. Thus they extend the wish to be free of suffering towards all sentient beings who are as infinite as the expanse of space. All of the methods that are related to bringing about that goal belong to the practices of great capacity or scope.

These practices are following the two broad categories. First is all of the practices that are related to cultivating the altruistic intention or bodhicitta and the second category is all of the methods for engaging in the bodhisattva practices following the generation of the altruistic intention. As for the procedure for training one’s mind in generating this altruistic intention, there are various methods.

One method is the Seven Point Cause and Effect Method and the other is method of Exchanging and Equalizing Self and Others. As the result of either of these two methods or through a combination of both methods, once one has gained the realization of bodhicitta, this altruistic intention then the practitioner needs to affirm this by participating in a ceremony of affirming the aspirational aspect of bodhicitta. Having so participated this is then followed by taking the Bodhisattva Vows.

Now as for the actual process of the procedure for generating bodhicitta by following Seven Point Cause and Effect method, I earlier explained that in order to cultivate compassion first one must cultivate the various components that necessary for generating compassion. One of these components is a deeper understanding of the nature of suffering that one does not wish others to experience and to be free of. This deeper understanding of suffering as I discussed earlier must be generated and cultivated on the basis of one’s own personal experience of the various types and levels of suffering. On the basis of this insight into the nature of suffering one needs to develop a deep sense of revulsion for this suffering and develop a genuine desire to seek freedom from this suffering. One’s desire to seek freedom from suffering arises from one’s feeling of the unbearableness towards one’s own suffering. Once one develops this then in cultivating compassion one needs to extend this deeper insight into one’s own suffering on to other sentient beings. One complements this by cultivating a sense of empathy or connectedness with others.

It is relation with this particular practice that one can see the difference between the Seven Point Cause and Effect method and the Exchanging and Equalizing of Self and Others method. These two methods are different means of cultivating a deep sense of empathy or connectedness with others. In the case of the Seven Point Cause and Effect method the main approach is to focus on cultivating a manner of relating with all beings by viewing them as one’s most dear relation such seeing all sentient beings as one’s mother and so on. One then reflects upon the great kindness of these sentient beings whereas in the method of Exchanging and Equalizing Self and Others the approach is not viewing all beings as being dear to one like one’s mother but rather to go further and to recognize that even one’s enemy is a source of tremendous kindness.

Thus one extends this recognition of the kindness of all sentient beings regardless of whether or not they are currently considered close to one. This is then followed by reflecting upon the disadvantages of self-centeredness or self-cherishing and the advantages and virtue of the thought cherishing the wellbeing of others. This is done by finally concluding that the though cherishing others’ wellbeing is the source of all goodness, all virtue and all excellence. Self-centeredness and the attitude of self-cherishing are seen as the source of all undesirable events, al negative consequences and all calamities. Through this way one develops a feeling of empathy, intimacy and connectedness with all other sentient beings.

As the result of cultivating a deeper understanding of these various methods and engaging in their practices and one gains a certain level of realization of bodhicitta then at that point one needs to affirm it formally by participating in a ceremony of generating the mind of enlightenment. This is explained in the text starting with verse six. The actual ceremony for generating the aspiration is explained from verse six on where it reads:

For those excellent living beings

-

Who desire supreme enlightenment

I shall explain the perfect methods

Taught by the spiritual teachers.

Facing paintings, statues and so forth,

-

Of the Completely Enlightened One

Reliquaries and excellent teachings

Offer flowers, incense, whatever one has.

With the seven-part offering

8 From the Prayer of Noble Conduct

With a thought never to turn back

Until one gains enlightenment.

With strong faith in the Three Jewels

9 Kneeling with one knee on the ground

And one’s hands pressed together

First of all take refuge three times.

Next, beginning with an attitude of love for all living creatures

10 Considering beings, excluding none

Suffering in the three bad rebirths

As suffering birth, death and so on.

Since one wants to free these beings

-

From the suffering of pain

From suffering and the causes of suffering

Arouse immutably the resolve to attain enlightenment.

From this point on the virtues and benefits of generating this aspiration is explained.

The qualities of developing

12 Such an aspiration

Are fully explained by Maitreya

In the Stalks in Array Sutra

Having learned about its infinite benefits

13 Of the intention to gain full enlightenment

By reading this sutra or listening to a teacher

Arouse it repeatedly to make it steadfast.

The Sutra Requested by Viradatta

14(a,b) Fully explains the merit therein

From this point onward the scriptural sources for these merits are given.

14(c,d) At this point in summary

I will recite just three verses.

“If it possessed physical form

-

The merit of the altruistic intention

Would completely fill the whole of space

And exceed even that.”

“If someone were to fill with jewels

-

As many Buddhafields as there are grains

Of sand in the river Ganges,

To offer to the Protector of the World.”

“This would be surpassed by the gift of folding one’s hands

17 And inclining one’s mind

Towards enlightenment

For such is limitless.”

Having developed this sentiment constantly enhance it

18 Through concerted effort to remember

It in this and also in other lives

Keep the precepts properly as explained.

So up to this point is the ceremony for generating bodhicitta. From verse 19 the text explains the taking of the Bodhisattva Vows. It reads:

Without the vow of the engaged intention

-

Perfect aspiration will not grow

Make effort definitely for it

Since one wants the wish for enlightenment to grow

Those who maintain any

20 Of the seven kinds of individual liberation vows

Have the ideal prerequisite for the bodhisattva vow

And not others.

The Tathagata spoke of seven kinds of individual liberation vows

21 The best of these is the glorious pure conduct

Said to be the vow

Of a fully ordained person.

According to the ritual described in the chapter

-

On the discipline in the Bodhisattva Stages,

Take the vow from a good

And well-qualified spiritual teacher.

Understand that a good spiritual teacher

-

Is one skilled in the vows of ceremonies

Who lives by the vow

And had the confidence and compassion to bestow it.

However, in case one tries

24 But cannot find such a spiritual teacher,

I shall explain another

Correct procedure for taking the vow.

I shall write here very briefly

25 As explained in the Ornament of Manjusri’s Buddhaland Sutra

How when long ago when Manjusri was Ambaraja

He aroused the intention to become enlightened.

“In the presence of the protectors

-

I arouse the intention to gain full enlightenment

I invite all beings as my guests

And shall free them from cyclic existence.”

“From this moment onward

27 Until I attain enlightenment

I shall not harbor harmful thoughts,

Anger, avarice or envy.

I shall cultivate pure conduct,

28 Give up wrongdoing and desire

And with joy in the vow of discipline

Train myself to follow the Buddhas.

I shall not be eager to reach

29 Enlightenment in the quickest way

But shall stay behind to the very end

Even for the sake of a single being.

I shall purify limitless,

30 Inconceivable lands

And remain in the ten directions

For all those who call my name.

I shall purify all of my bodily,

-

And my verbal forms of activity

My mental activities too

I shall purify and do nothing that is non-virtuous.

This is how one engages in the training of generating bodhicitta, the altruistic intention. After having generated this altruistic intention, what are the actual deeds one must engage in, what is the task? The task is to engage in the practices of the Six Perfections.

These deeds of the bodhisattva which are embodied in teachings of the Six Perfections when elaborated are enumerated as the Ten Perfections. In this accounting the sixth perfection of wisdom is further divided into four which includes the Perfection of Power, the Perfection of Aspiration, the Perfection of Transcendental Wisdom. If condensed sometimes the Six Perfections are condensed in terms of the three ethical disciplines of a bodhisattva. These are the ethical discipline of refraining from negative actions, the ethical discipline of engaging in positive actions or wholesome actions and the ethical discipline of working for others’ welfare.

I think that not only these three ethical disciplines of bodhisattvas are comprehensive but also there is a definite order to these three, a definite sequence. This is because in order to be effective in one’s engagement in the ethical discipline of working for other sentient beings, first of all one must have the ability to live this ideal and for this it is necessary to engage in the ethical discipline of gathering virtues and engaging in positive actions. However to engage in positive actions one must first refrain from the negative actions of body, speech and mind. Therefore these three ethical disciplines of bodhisattvas are not only comprehensive but also have a definite order of sequence.

So although as I said earlier that although bodhisattva practitioners’ aim is really to help others, but in order to do this they must first take care of their own mental continuum. So it is not sufficient for a practitioner of bodhicitta to say that their only wish is to help others and entirely neglect the need to purify their own minds; this doesn’t work. It is inappropriate as the Tibetans say to use the language of working for others’ wellbeing but in actual practice doing nothing.

In the text from verse 32 the actual method of engaging in bringing about the welfare of others is explained. It begins with an explanation of the practice of tranquil abiding, how to cultivate tranquil abiding or shamatha. This significance of this is that in order to truly work for the benefit of other sentient beings it is helpful if one can develop a certain sensitivity to the needs of others, have some kind of ability to discern what is an appropriate level of teaching for a specific sentient being. Here Atisha describes in the text a method of cultivating a form of the ability to perceive others’ mental states, in other words clairvoyance or precognition. However for these qualities one must first gain a realization of tranquil abiding or samatha. In any case tranquil abiding and single-pointedness of mind, which is embodied in it, is a very crucial element of one’s practice. Although by itself single-pointedness of mind, the practice of tranquil abiding is nothing uniquely Buddhist. In fact the practice is recognized as being common to both Buddhist and non-Buddhist traditions in India. However this single-pointedness of mind is a faculty that is indispensable for one’s spiritual practice.

When one speaks about bringing about the transformation of the mind it is something that can take place if one continues to reflect upon whatever the teaching point is and reflect deeply on it. One then tries to develop a deep sense of conviction grounded upon understanding. Then on the basis of this it is possible to voluntarily embrace the discipline upon oneself and it is through this type of voluntary embracing of the practice that mental transformation can take place. Otherwise one cannot expect the transformation of the mind to take place simply by imposing some kind of discipline or rule from outside.

As for the actual method for bringing about this transformation of the mind, generally there are two primary methods that are used. One is to utilize the critical faculty to analyze things and through that way develop an understanding based on analysis. So this is the first method. The second method is that once one has arrived at a certain conclusion as the result of the analytic process then one places one’s mind single-pointedly upon the conclusion one has arrived at through analysis. One maintains one’s mind placed on and absorbed to this conclusion. So it is through a combination of these two methods, analysis and absorption or placement, that one can bring about the mental transformation that one is seeking.

During the application of both of these two methods it is important to maintain one’s focus upon the chosen object of meditation whether is the analytical meditation or one is placing one’s mind single-pointedly upon the arrived at conclusion. In both cases it is very important to maintain one’s focus undiverted from the chosen object of meditation because if one’s mind becomes diverted, distracted by some other object extraneous to one’s own practice then one’s mind will not have the strength or force it would otherwise posses.

Therefore the cultivation of single-pointedness of mind as explained in the teachings on tranquil abiding is very important. Generally speaking as for the object of one’s meditation on tranquil abiding or shamatha, one can choose an external object or an internal object such as one’s mind and so on. So the object of tranquil abiding can be anything that one chooses. However depending upon what kind of meditative process one engages in, one can describe that object as the object of tranquil abiding or the object of penetrative insight or vipasyana. This is because if the chosen object on which one is engaging, if this engagement is primarily analytical using one’s analytic faculties probing into the deeper nature of that object, then one’s meditation becomes vipasyana or penetrative insight. Otherwise if one’s meditation is primarily focused on cultivating single-pointedness of mind and maintaining this single-pointedness of mind then this meditation is for tranquil abiding or shamatha.

Of course one can also take emptiness as the object of one’s meditation for both tranquil abiding and penetrative insight but generally this is the case for practitioners who already have a realization of emptiness. So in the texts one finds such expressions as seeking meditation by means of the philosophical view, the view of emptiness or seeking the view by means of meditation. Generally speaking then there are both cases where an individual practitioner may have first gained a realization of emptiness and from that cultivated an experience of single-pointedness, tranquil abiding focused on emptiness. Or there are instances where an individual practitioner first cultivates tranquil abiding and then applies this to focus on emptiness.

For us however, for most of us it is very difficult to first have a realization of emptiness and then develop tranquil abiding focused on emptiness. This is because even if one has quite a deep intellectual understanding of the emptiness of inherent existence and then meditates upon it, it may feel as if one is cultivating a single-pointedness of mind focused on emptiness. However it is very difficult at the beginner’s stage to insure that one’s ascertainment of emptiness remains vibrant and firm. Often in the process of cultivating single-pointedness of mind one tends to lose the vibrancy or freshness of one’s understanding of emptiness. So speaking generally for average practitioners one must first cultivate tranquil abiding and then learn to apply this faculty of single-pointedness on to emptiness.

Now to read from the text from Verse 32 onward which explains first the need for cultivating tranquil abiding and then the method for doing so. It reads:

When those observing the vow of the active altruistic intention

32 Have trained well in the three forms of discipline

Their respect for these three forms of discipline grows

Which causes purity of the body, speech and mind.

Therefore through effort in the vow

33 Made by bodhisattvas for pure, full enlightenment

The collections for complete enlightenment

Will be thoroughly accomplished.

All Buddhas say that the cause

34 For the completion of the collections

Whose nature is merit and exalted wisdom

Is the development of higher perception.

Just as a bird with undeveloped wings

35 Cannot fly in the sky,

Those without the power of higher perception

Cannot work for the welfare of living beings.

The merit gained in a single day

36 By those who posses higher perception

Cannot be gained even in a hundred lifetimes

By ones without such higher perception.

Those who swiftly want to complete

37 The collections for full enlightenment

Will accomplish higher perception

Through effort, not through laziness.

Without the attainment of calm-abiding

38 Higher perceptions will not occur

Therefore make repeated effort

To accomplish calm-abiding.

While the conditions for tranquil abiding are incomplete

39 Meditative stabilization will not be accomplished

Even if one meditates strenuously

For thousands of years.

Thus maintaining well the conditions mentioned

40 In the collections of meditative stabilization chapter

Place the mind on

Any one virtuous focal object

When the practitioner has gained calm abiding

41(a,b) Higher perception also will be gained.

Since the achievement of tranquil abiding depends upon whether or not one is successful in gathering the right conditions for its realization, one finds in the scriptures various conditions mentioned for the practice of tranquil abiding. Some of these are seeking solitude as well as setting aside specific time for a deliberate, prolonged, concerted effort in the practice of single-pointedness of mind. When one engages in this practice one needs to have as many sessions as possible, very short sessions. The practice should be undertaken in such a way that there is no break during the day and night. There needs to be a complete cycle of many short sessions, one after another.

One also need to do this over a sustained period of time as the achievement of tranquil abiding will not occur by practicing only once and a while when one can find the time. Rather one needs to set aside a specific amount of time and practice over a sustained period of time. In addition one needs to insure the right and conducive way of life and environment. One needs to make sure that one has as little responsibilities as possible with as few concerns as possible. One also needs to maintain a sound ethical discipline as well as an appropriate dietary regimen, which can make a significant difference. The diet one follows needs to be suitable and appropriate for this kind of sustained cultivation of single-pointedness of mind.

So the realization of tranquil abiding is something not likely to occur through the simple practice of single-pointedness here and there. For those who are practitioners of Vajrayana Buddhism however in the context of the generation stage which is the sadhana practice, although generally many of those practice require the practitioner having already attained tranquil abiding, there are some allowances in the sadhana practices where as part of one’s meditation there are specific means for cultivating tranquil abiding. Given the various factors that are part of the Vajrayana meditation practices, it is said that in some cases the realization of tranquil abiding can be easier in the context of the Vajrayana practices.

When one is actually cultivating tranquil abiding one needs to choose an object of meditation. This object of meditation that is required for the practice of tranquil abiding is not something that is a visual image at the sensory level. Rather it is an image that needs to be cultivated at the mental level so the actual object of meditation is not a physical object but a mental image of the chosen physical object. Therefore these objects of meditation are sometimes referred to in the scriptures as meditative images or reflections on the meditative state of mind. One therefore first needs to cultivate familiarity towards the chosen object so that one can call to one’s mind this image at the mental level without having to visually look at the chosen object.

Once one has learned to call to one’s mind the chosen object of meditation one then needs to make a strong determination that one will retain the focus of one’s attention on this chosen object. With this determination one then tries to maintain this attention of focus to the chosen object of meditation. When one is placing one’s mind on this object of meditation then there are two elements that are crucial. One is the ability to retain one’s attention to the chosen object and the other is the aspect of the clarity and alertness of one’s mind. These two elements need to be present at all times because if there is no stability or the ability to sustain one’s focus on the chosen object of meditation then one’s mind will become distracted. One’s mind will become diverted by some other extraneous thought or object.

On the other hand even if one has the ability to sustain one’s focus but if there is no clarity, there is no alertness then the quality of one’s single-pointedness will lack sharpness. Therefore it is important to insure that both elements are present, the ability to sustain one’s focus and the element of alertness or clarity.

What undermines one’s ability to maintain one’s focus? It is distraction therefore distraction is one of the most important and main obstacles for one’s practice of tranquil abiding. That which undermines the ability to maintain one’s clarity of mind and alertness is mental excitement or mental laxity/sinking therefore these two factors of mental excitement and mental laxity are considered to be the most important obstacles to the cultivation of tranquil abiding. Generally speaking there are other obstacles such as mental scattering and mental dullness but they are gross forms of the two basic obstacles of mental excitement and mental laxity.

The meditator’s task therefore is to try to identify and develop a sensitivity to discern the arising of these obstacles in one’s mind. This can be accomplished mainly on the basis of one’s own personal experience by judging the thought processes in one’s own state of mind and to really see what is at play within one’s experience. One will understand that mental laxity arises when one’s state of mind is too relaxed. When the state of one’s mind is too downcast then laxity or sinking arises and in order to counter this one needs to find a way to uplift one’s mind which will counter mental sinking or laxity.

On the other hand when one’s mind is too uplifted then mental excitement arises. One then needs to find a means to bring the level of upliftedness down to a more sober state. So it is through these ways that the meditator needs to find for themselves subjectively and on the basis of one’s own experience a proper balance so that one’s mind is neither too excited nor too lax. One needs to have the right balance and this is something that needs to be done on the basis of one’s own personal experience of the practice.

Generally for Buddhist practitioners it is very beneficial to take the image of the Buddha as one’s object of meditation when cultivating tranquil abiding. If one does this it is quite helpful to choose an object that is the right size, not too large about an inch of two in height. One tries to imagine this image to be very brilliant and also rather substantial, having solidity. Imagine this image of the Buddha in front of one and one focuses one’s mind upon it cultivating tranquil abiding. This is most beneficial.

It is also possible to cultivate tranquil abiding on the basis of using one’s own mind as the object of meditation. This is the case in practices such as the Mahamudra or Great Seal tradition where when cultivating tranquil abiding the main object of meditation is chosen as one’s own mind. If one does like this it is first of all necessary to have some understanding of the object of meditation, which is one’s own mind. Here it is not sufficient to have only a definition of mind; mind is that phenomenon that is luminous and knowing. This alone is not sufficient, as one must have an experiential understanding of what mind is.

How does one cultivate such an experiential understanding of the mind so that one can use it as an object of meditation for tranquil abiding? One method is to do the following practice. One tries to see if one can bring about the cessation of all past recollections, all thoughts directed and that delve into past experiences. One tries to put an end to these types and thought and then one also tries to put an end to any thoughts projecting into the future. These can be anticipatory thoughts, fear or whatever thoughts concerning the future. One thus tries to clear away all thoughts focused on either past experiences and thoughts projecting into the future. Once one finds this then one tries to maintain this focus on the present experience. One then searches for the gulf or gap and experiences a sort of a vacuum as normally in one’s day-to-day experience not only during the active experiences of the sensory faculties but even in periods without obvious sensory experiences, one’s thoughts are always colored by conceptualization. It is almost as if one’s mind is totally wrapped in layers of conceptualization so what one is trying to accomplish is try to remove those layers of conceptuality away leaving an experience of mind-as-it-is.

This is accomplished by differentiating between thoughts dwelling on the past or dwelling on the future and the present moment. This initially may be experienced as a kind of a vacuum, a kind of a gulf with nothing. But this is not the emptiness that is spoken about; this is basically an absence of conceptualization that is directed on to the past or the future. Through prolonged and sustained practice if one can extend the gap or gulf that one experiences which initially may be very momentary, very fleeting but gradually as the result of continued practice one will be able to extend this period of the experience of the gap. Eventually one will gain a sense of what is truly meant by luminosity and knowing. One then uses that awareness as the object of meditation.

As a result of cultivating this meditative absorption, the process of which is described in the scriptures as involving nine stages of mental development, and these nine stages describe the gradual process through which the practitioner acquires greater and greater abilities to sustain their focus without distraction. Initially when one enters a meditative session one may experience more moments of distraction than moments of being able to maintain one’s focus of the chosen object. However gradually as the result of sustained practice then that situation will change so that at least during the meditative session one will experience more moments of single-pointedness than distraction.

Still as one pursues further into one’s practice then one will be able to refine one’s faculties of mindfulness and diligence. These two faculties of meditational practice will become more and more heightened so that they will be able to counter even the arisal of subtle levels of mental excitement or mental laxity. Thereby one gradually as the result of the increases force of one’s mindfulness and diligence reaches a point where in the meditation session one is able to retains one’s focus on the chosen object undistracted for as long as three or four hours. At this point the practitioner is said to have reached what is called the ninth stage of mental development. As the practitioner pursues the practice further then as the result of this heightened state of meditative absorption, one eventually experiences physical and mental pliancy, suppleness of the body and mind. This gives rise to an experience of bliss and at this point the practitioner has attained tranquil abiding or samatha.

From verse 41 line three on the text explains the necessity for cultivating the wisdom of emptiness. It reads:

41(c,d) But without the practice of the Perfection of Wisdom

Obstructions will not come to an end.

Thus to eliminate all obstructions

42 To liberation and omniscience

The practitioner should continually

Cultivate the Perfection of Wisdom with skillful means.

Lord Atisha then explains the importance of cultivating a union of the two.

Wisdom without skillful means

43 And skillful means without wisdom

Are referred to as bondage

Therefore do not give up either.

To eliminate doubts concerning

44 What is wisdom and what is skillful means

I shall make clear the difference

Between skillful means and wisdom.

Apart from the Perfection of Wisdom

45 All of the virtuous practices

Such as the Perfection of Giving

Are described as skillful means by the Victorious Ones.

Whoever under the influence of familiarity

46 With skillful means cultivates wisdom,

Will quickly attain enlightenment

Not just by meditating on selflessness.

The question arises, if one needs to cultivate wisdom unified with skillful means, what kind of wisdom must one cultivate? Generally speaking there are many different types of wisdom. For example the scriptures speak of the wisdom of understanding the conventional reality such as the five fields of knowledge as well as the wisdom understanding ultimate reality. Here the text identifies what is meant by wisdom. It reads:

Understanding the emptiness of inherent existence

47 Through realizing the aggregates, constituents and sources

Are not produced

Is described as wisdom.

The question arises, if the wisdom realizing the absence of inherent existence of the aggregates and so on is the wisdom that needs to be cultivated here, how does one understand this wisdom of emptiness? When one looks at the aggregates, the constituents, elements, sources and so on do they have origination or come into being from causes? If so how can they be said to be devoid of inherent existence?

The point made in the text is not that one is denying that those phenomena such as the aggregates, elements, sources and so on do not posses any origination nor that they do not come into being through causes. Rather what is being rejected here is that phenomena come into being, their origination is somehow intrinsic to their nature or somehow that phenomena posses any kind of intrinsic existence. For example when one conventional makes the claims that from such-and-such causes that such-and-such effect ensues, for such-and-such factors that such-and-such results come about. When one makes such claims, one makes them at the level of conventional reality without probing or exploring deeper into the ultimate nature of phenomena.

If one is unsatisfied by an understanding of things, the operation of cause and effect at the mere level of appearance, the mere level of conventional truth then if one seeks for some sort of inherent existence of cause and effect then the more one searches one fails to find anything that can withstand such critical analysis. Therefore this unfindability is described as suggesting the absence of inherent existence. This mode of looking beyond what one directly perceives, looking for some kind of ultimate nature of things and events, an ultimate mode of being is described as seeking the ultimate truth or seeking their true mode of being. This true mode of being is their nature, which is described in the scriptures as emptiness and the realization of this emptiness is what is meant by wisdom in the context here.

As I explained earlier one should not have the notion that somehow there is an isolated emptiness that is independent of everything, that it exists “out there” on its own, not dependent upon any object or basis. When one speaks of emptiness one is speaking about the ultimate nature of things and events therefore emptiness can only be understood in relation to things and events. Therefore emptiness always needs to be explained on the basis of some object or basis and what is involved here is the quest or search to understand whether or not things and events exist in the manner in which one perceives them.

So when one is seeking to cultivate the wisdom of emptiness what one is seeking is to really understand is what the ultimate mode of being of things and events actually are. What is the ultimate nature of these things and events? Therefore one can never cultivate an understanding of emptiness divorced from the world of multiplicity. Because of this Nagarjuna stated in his Fundamentals of the Middle Way that without depending upon the conventional truth one would fail to realize the ultimate truth.

[Without a foundation in the conventional truth,

-

The significance of the ultimate cannot be taught

Without understanding the significance of the ultimate

Liberation is not achieved.]

(Mulamadhyamikakarika, Chap. XXIV)

Also in Santideva’s Siksasamuccaya, the Compendium of Practices where he presents the teachings on emptiness he provides a profusion of citations from many different Mahayana sutras that all present an enumeration or lists of various categories of the path along with a taxonomy of reality. Based upon these categories and taxonomy Santideva explains emptiness. This is similar to what I said yesterday that in a sense what happens is that by presenting all of those vast citations one is building an edifice. After having built the edifice the point is then made that all of that is devoid of inherent existence; none of the categories or taxonomy possesses inherent existence. So in a sense there is a process of dismantling as well.

The point is that what is involved in developing the wisdom of emptiness is the analysis to determine whether or not things and events exist in the manner in which one tends to perceive them or whether there is an ultimate mode of being, something different from the way in which one tends to perceive them. This really is the crux of the meditation on emptiness.

The basis on which one is cultivating one’s understanding of emptiness are things and events that have a direct bearing on sentient beings’ experiences of pain and pleasure. These are objects whose existence one cannot deny; they are real and have an impact on one’s experience.

Furthermore in the scriptures the understanding of dependent origination is stated to be the most powerful means of arriving at direct knowledge of emptiness. So dependent origination is described as the most powerful proof of emptiness. This suggests that when engaged in the quest for understanding emptiness and as a result of deductively analyzing the aggregates and so on, then one does not when one fails to find an entity that possesses intrinsic reality, one does not arrive at the conclusion that therefore it does not exist at all. One does not draw this conclusion but rather one draws the conclusion that since an intrinsic identity cannot be found when searched for through critical analysis then things and events must only exist by means of dependent origination. Therefore a genuine understanding of emptiness must take place where the moment one reflects upon one’s understanding of the emptiness of inherent existence that this very understanding indicates that things exist. One should feel almost as if when one hears emptiness, the implication that things and events exist through dependent origination arises spontaneously. Therefore a genuine understanding of emptiness is said to be where one understands emptiness in terms of dependent origination.

A similar point can also be raised in Nagarjuna’s Precious Garland where when explaining the emptiness of the person, the selflessness of person he proceeds by explaining how in a reductive analysis he shows how the person is not the earth element, water element, fire element and so on. He approaches this analysis first through this reductive process. After then failing to find something called person independent of the elements and having failed to find the person to be identifiable as any of the elements separately or together, he then raises the question, if this is the case where is this person?

After this Nagarjuna does not immediately conclude that therefore the person does not exist at all but rather he then immediately brings up the idea of dependent origination. He states that the person is therefore dependent upon the aggregation of the six elements. The point raised is that the person exists and that the person is real. The person undergoes the experiences of pleasure and pain and also the elements that constitute the person’s existence are also real. The elements can impact on the person’s experience. Although the person exists, when one looks for it among the various elements that constitute the individual, which in a common sense way is where one could normally expect to find it, one fails to find the person within the elements where one would expect to find it.

The question then arises, in what manner can one understand this existence of the person? There Nagarjuna brings up the concept of dependent origination. He states that one can therefore understand the person’s existence only in terms of its dependent origination. Having made the point of the dependent origination he then concludes that therefore the person is devoid of intrinsic existence. So this is an important point where the transition is from the reductive analysis failing to find the person then next is the assertion of dependent origination. As a result of understanding dependent origination one then arrives at the final conclusion that the person is devoid of inherent existence.

[A person is not earth, not water,

80 Not fire, not wind, not space,

Not consciousness, and not all of them.

What person is there other than these?

Just as a person is not real

-

Due to being a composite of six constituents,

So each of the constituents also

Is not real due to being a composite.

If [it is answered that] fire is well known [not to exist without fuel but the other

three elements exist by way of their own entities],

-

How could your three exist in themselves

Without the others? It is impossible for the three

Not to accord with dependent-arising. ]

Precious Garland

Similarly in the Twenty-fourth Chapter of Nagarjuna’s Fundamentals of the Middle Way, one finds a question or objection being raised from the Buddhist Realists who charge that the Madhyamikas, the proponents of emptiness are nihilists. The objection is that if things and events are devoid of inherent existence, which means that all of samsara and nirvana are devoid of inherent existence. If this is the case the essentially what the Madhyamikas are saying is that nothing exists; everything is empty. The objection states that if Nagarjuna maintains that all phenomena are devoid of inherent existence then this is tantamount to making the assertion that nothing possesses any existence. Therefore Nagarjuna’s view is nihilistic.

[If all of this is empty,

-

Neither arising, nor ceasing,

Then for you, it follows that

The Four Noble Truths do not exist.

If the Four Noble Truths do not exist,

-

Then knowledge, abandonment,

Meditation, and manifestation

Will be completely impossible.]

(Mulamadhyamikakarika, Chap. XXIV)

To this objection Nagarjuna replies that such an understanding of emptiness as nothingness as the Realists present is a misconception of Nagarjuna’s view. By emptiness the Madhyamikas do not mean mere nothingness. By emptiness the Madhyamikas mean dependent origination. Nagarjuna then explains that whatever is dependent originated he asserts that to be empty and in turn he asserts that to be dependently designated or labeled. This Nagarjuna calls the Middle Way. The point being made here is that by making the statement that all dependently originated phenomena are devoid of inherent existence Nagarjuna is saying that the Madhyamikas transcend the extreme of absolutism by rejecting any absolute reality of things. By stating that all things and events are devoid of inherent existence yet posses a dependent nature, that things and events exist as dependent originations, Nagarjuna transcends the extreme of nihilism.

[We say that this understanding of yours

-

Of emptiness and the purpose of emptiness

And of the significance of emptiness is incorrect.

As a consequence you are harmed by it.

Whatever is dependently co-arisen

-

That is explained to be emptiness.

That, being a dependent designation,

Is itself the middle way.]

(Mulamadhyamikakarika, Chap. XXIV)

Thus this freedom from the extremes of nihilism and absolutism represents the true Middle Way. Having made this identification of the understanding of emptiness as the true Middle Way Nagarjuna goes on to make the following statement. There is nothing whatsoever that is not dependently originated therefore there is nothing whatsoever that is not devoid of inherent existence.

[Something that is not dependently arisen,

-

Such a thing does not exist.

Therefore a nonempty thing

Does not exist.]

(Mulamadhyamikakarika, Chap. XXIV)

This is Nagarjuna’s understanding of dependent origination in which he accepts nothing whatsoever that is not dependently originated. This is because Nagarjuna accepts nothing whatsoever that possesses inherent existence. The question arises; does this imply that according to Nagarjuna that all phenomena both transient as well as permanent phenomena are dependently originated? It is helpful here to understand that there are different levels of meaning to the concept of dependent origination.

For example on the first level one can understand the notion of dependence in terms of causes and conditions. So this understanding of dependent origination is relevant to the world of causes and effects. Here the dependence is understood in terms of dependence upon causes and conditions.

However there is second understanding of dependent origination that only covers conditioned things. A subtler level of dependent origination is where dependence is understood in terms of mutual dependence; for example in the case of the mutuality of concepts, when one speaks of long and short. Here there is a mutuality of concepts in that something can only be posited as long in dependence in relation to something short. Similarly when one looks at things one can understand that thing or event as having parts in relation to the whole with whole constituted by its parts. The parts can only be posited in relation to the whole that is the composite of those parts. In this sense one can understand the entire world, both conditioned and unconditioned as being dependently originated.

Also there is a third level of the understanding of dependent origination where dependence is understood in terms of the subject, the labeling mind. For example when one states that something exists and if one were to look for the essence of this object objectively nothing is able to withstand such critical probing. So when one searches for whatever it may be, when one searches for it objectively there is nothing whatsoever that can be referred to the true referent of the term. This does not suggest that whatever the mind labels becomes real. Of course the labeling process is there but also what is labeled must not be invalidated by another conventional knowledge. Also it must not be invalidated by the critical analysis that probes into its ultimate nature. When one labels something as some thing and look for its true referent of the term labeled objectively, there is nothing that really stands out to justify the label given to that thing.

What does one conclude from this? Nothing possesses absolute, objective reality. The existence of things can only be understood and posited only as mere appellations, mere designations or mere names. One can therefore see that there are broadly speaking three levels of meaning to the concept of dependent origination. According to Nagarjuna dependent origination covers the entire spectrum of reality.

However Nagarjuna’s understanding of emptiness as the absence of inherent existence of all things and events is something that is of course accepted by all. For example yesterday I spoke about the Third Turning of the Wheel of Dharma and one of the principal texts of that turning is the Samdhinirmocana Sutra, the Sutra Unraveling the Intention of the Buddha, which is one of the primary scriptures for the Mind-Only School. The Mind-Only School does not accept literally the statements found in the Perfection of Wisdom Sutras where there is a categorical negation of inherent existence across the entire spectrum of reality.

So the followers of the Mind-Only School do not accept that those statements should be taken literally. They contextualize those statements by differentiating between three natures of phenomena. These are designated or imputed nature, the dependent nature and the perfect nature. In relation to these three natures, the Mind-Only School contextualizes and interprets the Buddha’s statement that all phenomena are devoid of inherent existence. They differentiate meanings according to the context whereas the followers of the Middle Way School, the Madhyamika School accepts those statements from the Perfection of Wisdom Sutras as definitive and accept the categorical rejection of inherent existence across the entire spectrum of reality.

If one can understand the principle of dependent origination in terms of mutual dependence of concepts that I spoke about earlier then there is a certain simplicity to one’s worldview because one can then posit the existence of things in relation to other things. For example one can then posit or define objects in relation to subjects, one can define objects of knowledge in relation to cognitions or one can define various things in relation to others. Therefore they will be a certain symmetry and also a kind of completeness to one’s worldview.

There will be no need to struggle in the way in which the Mind-Only School struggles where in order to verify the existence of objects they posit valid cognition. In order to verify the existence of these valid cognitions then they need to posit a further faculty that is all-perceptive, reflexively self-cognizing and so on. This kind of problem arises when one fails to recognize the absence of inherent existence across the entire spectrum of reality and make distinctions between the world of internal consciousness or mind and the world of external objects. For example the Mind-Only School denies the reality of the external world of matter and maintains that the internal world of the subject such as consciousness and so on enjoy a greater reality. They thereby accord them a kind of inherent existence.

This is completely contrary to way in which the Madhyamika School understands the nature of the world. They understand the existence of things in terms of mutual dependence, the concept of dependent origination. Thus the Madhyamikas are able to maintain that all things and events including subjects, objects, valid cognitions along with their objects of knowledge and so on are all mere designations, mere labels or mere appellations.

If one is not able to truly understand the world in terms of this principal of dependent origination with one feeling the need to truly posit some sort of objective reality to things, then one runs into all sorts of problems. For example if one is searching for what exactly is the nature of a person or self then if one engages in this analysis with an underlying belief that there must be a person somewhere that is objectively real that is findable at the end of one’s search, then one is compelled to posit all sorts of means to identify what this objectively real person would be. In the example of the Mind-Only School there was the attempt to identify person or self with the mental consciousness and in some cases the mental consciousness is found to be too transient. This then lead to the need to posit another faculty that is supposed to have a much more enduring status called the foundational or storehouse consciousness, the alayavijnana.