His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama: I think there are two different ways to overcome depression. One way is to increase or develop the realization of our own potential; to understand that no matter how weak we may sometimes be at a superficial level, deep down there is no difference between the Buddha and us.

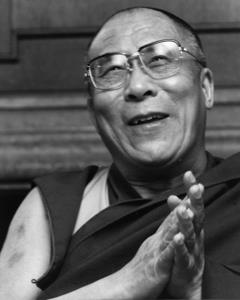

By His Holiness the Dalai Lama at Dharamsala, India (Last Updated Nov 5, 2012) An audience with His Holiness the Dalai Lama at Tushita Meditation Centre, Dharamsala, India, in November 1990. His Holiness discusses a range of topics, including karma, other religions, depression, Buddhist tenets and the mind. Transcribed and edited by Ven. Thubten Chodron. Second edit by Sandra Smith, November 2012.

Question: How do we gain conviction in karma? Does karma function only if we believe in it?

His Holiness the Dalai Lama: I think there are two ways to think about this. First, Buddhists don’t accept a creator. If we accept a creator as fully compassionate, all-knowing and omnipotent, then that creator is the ultimate reality or ultimate truth. A creator is something independent, however, from the Buddhist viewpoint, this presents some contradictions, so a creator is not easy to accept.

There’s no almighty creator, but at the same time we have to accept that things are changing all the time, so we have to find out the causes and conditions for that change. From that perspective comes the discussion of karma. That is one way of thinking about karma.

The second way to think about karma is that even our food, clothes, shelter and daily life experience depend on causes or actions; mainly the actions of sentient beings, those who have mind and experience. Our daily experiences happen due to our actions, which are done with certain motivations. Due to various motivations, different actions bring different results. That’s our daily experience.

The events of tomorrow depend a great deal on today’s actions. Some of today’s actions may produce results immediately, but some actions will bring their results after 10 days or 100 days or 1,000 days. This is the usual way things function. Karma means action. For example, due to our verbal, physical and mental actions, certain results come immediately. Also, due to today’s actions, some results may develop after some time; in some cases after a few years. That’s the law of karma or action. Since Buddhists accept the continuity of mind, we believe in many lives, infinite lives. Therefore, some results of today’s actions may happen after 10,000 years or 100,000 years, in different lives. This level of karma is one presentation we can talk about and think about.

On another more complicated or deeper level, we have to accept universal natural laws. Take these plants for example. Of course, due to certain causes and conditions they arose, but the plants themselves do not have consciousness. We do not believe that they are sentient beings, however, plants are created due to karma or action. Karma is created by someone who has motivation, who has experience, and who acts. The seed grew into a plant, but I don’t think there is any karmic connection between the seed and the plant.

We have to accept that the whole universe arose due to sentient beings’ karma. Therefore, the whole universe or planet happened because there are sentient beings who utilize this planet. Take the example of a building, which will be used by other human beings. Someone planned and then began to build it. The person who planned or constructed that building doesn’t necessarily live there, however, the construction happened because of that person. Similarly, when the planet first formed, there were no sentient beings on it, but there were definitely sentient beings who came afterwards. That is the Buddhist belief.

Plants definitely have some connection with the sentient beings that use them. I think plants probably happened due to the collective karma, not only of human beings, but also of insects. Today we human beings enjoy the beautiful color, shape and good smell of these plants. Bees use the nectar from the plants, some birds use them for shelter and some small insects use them for shelter and food. For some small birds, plants are their castle, so when something threatens them, they immediately run into the bushes. I think these things happen due to the collective karma of those beings.

From the Buddhist viewpoint, karma is a natural process; it doesn’t depend on whether or not we believe in it. Whether we accept this natural process or not, it exists. This is a little bit complicated, for example, it is very difficult to say whether there is a creator or not. We Buddhists have our own system and certain ways of investigating and experimenting. If we analyze this, we may find contradictions if we try to accept a creator. At the same time, from the viewpoint of those who accept a creator, there is a creator, even though Buddhists do not accept it. Similarly, from a Buddhist viewpoint, someone may not accept the theory of karma, but there is still karma. If we approach a non-believer, they would answer that there is neither. This is complicated.

I believe that the theory of emptiness can easily be explained whether you’re a believer or non-believer. Topics like subtle impermanence can also be explained. I think these points can be understood even from a physicist’s scientific point of view. We can say that things are not independently existent and if others ask if this is the ultimate nature, we can say that it is and we can explain it.

An independent creator cannot be explained, but this doesn’t mean there is no creator. In a certain sense, it is possible to accept that there is a kind of creator, but it isn’t necessarily something independent. It seems that the presentation of a creator by those religious systems that have fundamental faith in a creator isn’t based on a long analysis of whether or not there is independent existence. It isn’t based on analysis which leads those involved into complicated analytic meditation. I think the concept of creator is mainly for the sake of promoting human beings’ good qualities.

From the Buddhist viewpoint once you accept a creator, it isn’t necessary to go to the extreme of saying that the creator is independent of causes and conditions. Generally speaking, even Buddhists can say Buddha is a creator to a certain extent. Do you understand this?

Question: What is Buddha the creator of?

His Holiness the Dalai Lama: Generally speaking, we pray to Buddha and we accept that Buddha has extraordinary qualities, therefore, it is obvious that Buddha’s intelligence and ability are much greater than ours. If we follow his teachings properly we get some benefit, so from that viewpoint, any benefit we receive was created by Buddha.

Christians don’t say that someone who doesn’t accept Jesus Christ will ultimately achieve salvation because God is the creator; they say that to achieve salvation, we should follow Jesus’ teachings properly. Even after accepting a creator, it seems that results arise depending on other causes and conditions.

The other day I met a Jewish group. They explained that God is ultimate reality, ultimate truth. They also emphasized that each individual human being has responsibility and they don’t believe that everything is in the hands of God. They believe that God is the creator and at the same time we have a heavy responsibility to build a happier humanity and a happier world. They believe that although God is the creator, we human beings have a certain amount of shared power. There is a partnership between God and human beings, so in that sense we are also a small creator.

Therefore, there are different interpretations of God as the creator. To a certain extent, from a certain viewpoint, we can call Buddha a creator, though not necessarily something absolute. If we accept Buddha or God as an absolute, there are contradictions according to the Buddhist viewpoint.

Question: Why do people get depressed and what are some meditation techniques to overcome depression and fear?

His Holiness the Dalai Lama: According to some scientists and psychologists, these problems of depression and mental unrest are due to the lack of affection; the lack of love and compassion at the family or community level. Their explanation is that mental depression often develops as a result. Human beings are naturally social animals and our basic nature is such that we appreciate others’ affection very much, so when we receive insufficient affection or we are deprived of affection, then we become very unhappy. It is beneficial to consider this when we meditate; it helps increase the strength of our love and compassion.

What techniques we should use to counter depression and fear depend very much on the individual person—whether we’re a believer or a non-believer, and if we are a believer, what kind of belief. So there are different techniques according to the individual. For a Buddhist, the teachings on buddha nature is very useful.

Also, I think there are two different ways to overcome depression. One way is to increase or develop the realization of our own potential; to understand that no matter how weak we may sometimes be at a superficial level, deep down there is no difference between the Buddha and us. We all have Buddha nature, therefore, all people will eventually become Buddhas. There is the possibility for everyone to become a Buddha. Buddha nature isn’t anything unique to the Buddha; everyone has this same quality. It is very important recognize our own ability, our own potential.

On the other hand, at the present moment we are under the control of disturbing attitudes and ignorance. As long as the disturbing emotions are there, some kind of problem is always there, but it is useless to worry. For example, when there is something wrong with our body, then pain comes. The pain is symptomatic of that underlying illness, so just worrying about the pain is silly, it is useless.

If we really don’t want to have the pain, we must concentrate on the underlying cause of the pain. If there is a possibility to remove it, we should try to do this, but if there is no possibility, there is no use in worrying about it. Similarly, we can think about the basic nature of cyclic existence. This body is influenced by ignorance, so as long as that ignorance is there, some kind of problem is always there. That is why we want to achieve liberation or nirvana.

There are two ways to counteract depression and fear. First, we can realize our own potential to increase and develop inner strength, and secondly, we should realize the nature of suffering. We should accept the reality of the nature of suffering. So there are these two ways to remove fear and depression.

Question: If all phenomena and their bases of imputation are merely imputed by conception, how is it possible for a sense consciousness to know an object directly without conception? What causes that sense consciousness to arise if it precedes a conception?

His Holiness the Dalai Lama: Although all phenomena and their bases of imputation are imputed by conception, it’s not necessary that the phenomena and the conception designating it should always be there at the same time. I’ll tell you a little story. One Amdo monk came to visit a senior lama to clarify some doubts. He said, “My doubt is that it says in the scriptures that all phenomena are merely designated by thought or conception.” The lama replied, “Yes, that’s a very difficult point.” After the monk left the room, he said, “It’s not necessary that the thought designating those phenomena should always be tied to those phenomena.”

The point is that when a sense consciousness sees particular phenomena, there is no relation with conception or thought. For example, when a thought apprehending form realizes the form, then that thought is induced by a sense consciousness. It’s not the other way around. If we ask whether the focal object of an eye consciousness is designated by thought or not, we have to say that it is definitely designated by thought.

Saying that form is designated by thought is a general explanation, but we are not saying that the thought induced by the sense consciousness has designated that form, because that thought has yet to arise. If we analyse and try to find whose thought has designated this form—mine or yours—we will not be able to explain it. Similarly if we ask if this form has been designated in the past, present or future, we will not be able to explain it. If we try to analyse in that way, we are going beyond that limit and trying to find something that is inherently existent. This is because imputation by thought is itself imputed by thought. If imputation by thought had inherent existence, then of course we should be able to find it, but again it is imputed thought, so we will not be able to find it if we analyse in that way.

When we say that phenomena are merely imputed by mind, we know that for phenomena to exist, they must have only nominal existence. That nominal existence is designated by thought, therefore it exists. It can produce a result and it has its own causes, so there is something. That phenomenon can give us a pleasant or unpleasant experience, so it definitely exists. If we try to investigate the very nature of those phenomena, the conclusion is there is something, but we cannot find it. The ultimate answer is that it exists due to designation and its existence is just through renown. The conclusion is that things exist, but they don’t have an inherent mode of existence. Since we’re sure that they exist nominally and that we experience them, then the only recourse open for us is that their existence is based on the mind. Did that clarify this question?

Question: How can we think about the mind stream and understand what it is?

His Holiness the Dalai Lama: Is there anyone doing calm abiding meditation on the mind? Unless we get some experience or awareness of consciousness, it is very difficult to explain the continuity of mind, therefore it is quite useful to meditate on the mind. How can we do this? As a first step, it is necessary to develop some kind of thought control, to deliberately stop memories of the past and all thoughts of the future. Stop all of these. When we stop these two, we immediate have an understanding or feeling that is almost like nothingness. Usually our thoughts are reflections of external things—color, shape and things that we experience. When we stop all these thoughts, what is left? At the beginning, we may feel some kind of nothingness. Although it is not nothingness, because our thoughts are usually involved so much with external matters, when they are removed we feel empty.

Then, try to meditate or remain in that state of mind. Eventually we get some kind of feeling that there’s something like an infinite mirror; a mirror with infinite dimensions. The mirror itself is clear; no particular thing is there, but whenever it contacts things, a reflection immediately arises. We can get an understanding of the mirror-like clarity of the mind this way. Whenever the mind comes across a phenomenon, it immediately gets a reflection of it, but its own nature remains like that of a mirror, completely clear. That is the way to realize mind.

Also during sleep, when we’re just going to sleep or just after we wake up, the sense organs aren’t fully developed. When we just wake up and sleep has ceased, if our physical condition is normal and fresh, we may get some kind of feeling about the mind during that moment. The problem is that we are not usually able to remain on that event. If we try to catch that event, it will help us to understand the clarity of the mind. If we try to catch it, an experience of the grosser level of clear light will come. This is very useful, however, it is not a unique Buddhist practice; it is common to both Buddhist and Hindu traditions.

Question: Please talk about the relationship between a Dharma teacher and a student. What are the most important elements in it?

His Holiness the Dalai Lama: The most important thing is to have a fully qualified master. At the beginning, it’s very important to develop a stable and careful reliance on the teacher. We should have an understanding of the qualities of a spiritual master as explained in Lama Tsongkhapa’s Lam-rim Chen-mo. That presentation is quite well-balanced and there is less danger of confusion. Some texts stress faith very much and there are statements like, “See everything the spiritual master does as good.” Some texts emphasize such points, but these statements only apply if the lama and disciple are fully qualified. On that basis, this advice is very good. An example is Naropa and Tilopa—there is no problem for them. But, I think it’s better to approach the relationship in a more balanced way if the lama and disciple are semi-qualified.

Question: Please advise how beginners can improve their meditation.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama: That’s difficult to say. I think due to the individual’s mental disposition, it’s difficult to generalize. It’s advisable to choose a meditation object according to one’s disposition. For some people, meditation on impermanence is more beneficial and they can concentrate better on that. In some cases, it’s beneficial to just meditate on the breath. For some people, meditating on oneself as a deity is more effective and easier. In some cases, it’s good to visualize a deity in front of you, but for other people, it’s recommended to visualize light or a mantra or seed syllable in certain parts of the body. It’s up to the individual taste.

The most important factor is time. For a person who is very busy and has little patience, meditation is almost impossible. For that person, just reciting a short prayer and then finishing is best.

Question: Why is it said that the mere I and not the subtlest mind is what carries the karmic imprints from one life to the next?

His Holiness the Dalai Lama: This is said because the explanation of the innermost subtlest consciousness isn’t found in the lower three tantric classes or in sutrayana. Generally, both sutrayana and the lower tantric classes accept a subtle consciousness. This is not the subtlest consciousness, but a comparatively subtle consciousness. This is usually believed to be unspecified, but it is still a temporary type of consciousness. Since they don’t accept the innermost subtle consciousness, they say there are certain moments when there is no consciousness, when we are completely unconscious. For example, there are events such as deep sleep and fainting during which we aren’t conscious.

The Cittamatrins, who accept the mind as the basis of all, say that since the person is unconscious during such states, there must be one consciousness where the imprints are deposited. According to the Madhyamaka, we are unable to accept the mind as the basis of all the repository of imprints, so this explanation of the subtlest consciousness isn’t found in the Madhyamaka. Therefore, it’s said the mere I, which is designated on the continuity of the mind, is the basis of imprints. According to explanations in the Maha-annutara Yoga Tantra, the innermost subtlest consciousness is still there when the person is unconscious, therefore, that subtle consciousness is the basis of the imprint.

Then comes your earlier question whether all phenomena are the entity of clear light. That is very complicated and difficult. There are different explanations according to Sakya, dzogchen and Gelug. It seems that the dzogchen tradition has a very good, all-encompassing explanation. Here, it’s like the explanation that thought designates phenomena. We are talking in a general way and we aren’t saying that all phenomena arise from clear light. This is explained through the illogical nature of holding other extremes; we come to the conclusion that these arise from the clear light. Talking about phenomena arising from the nature of clear light, it’s not the same as the Cittamatra saying that all phenomena are the entity of the mind.

Question: Is it possible for people following other religions to attain enlightenment?

His Holiness the Dalai Lama: That depends on what they say is the meaning of enlightenment. Each faith and each different system explains enlightenment from its own perspective. Can enlightenment according to the Buddhist concept be achieved through other teachings? Generally speaking that’s difficult, because achieving the enlightenment that Buddhists explain, we have to eliminate ignorance—the conception grasping at true or inherent existence. Eliminating that ignorance through understanding suchness is the basis on which enlightenment is attained.

From the viewpoint of Prasangika Madhyamaka, through practicing only the view (of reality) according to other traditions or according to the lower Buddhist tenets—Svantantrika Madhyamaka and below, we won’t be able to actualize enlightenment. This is because the view according to these lower tenets can’t remove subtle ignorance. Unless that ignorance is removed, we can’t attain enlightenment. Christians accept God as absolute creator and they accept a soul, which implies they accept independent existence. Therefore, when someone accepts a soul it is difficult to accept emptiness. Also, regarding the Christian view of heaven and final judgment —I think when that happens Buddhists may remain somewhere else at that time; all the Buddhists will gather together at Bodhgaya. Font http://www.lamayeshe.com/index.php?sect=article&id=856