His Holiness the Dalai Lama: Nagarjuna’s Precious Garland says that: “The person is neither the earth element nor the water element” and so on.

16 His Holiness the Dalai Lama: Teachings on Lam-rim Chen-mo

His Holiness the Dalai Lama: Nagarjuna’s Precious Garland says that: “The person is neither the earth element nor the water element” and so on.

Day Six, Morning Session, July 15, 2008 at Lehigh University, Pennsylvania, USA. Part one. Generating the Awakening Mind: Introduction. Visualization and the Seven-Limbed Practice. Ceremony for Generating the Awakening Mind. Avoiding Nihilism (cont.). Dependent Origination and Emptiness (cont.).

Heart Sutra in Chinese and English

Generating the Awakening Mind: Introduction.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So today, at the beginning of the session, I thought we could do the ceremony for generating the awakening mind.

His Holiness: [begins in Tibetan (translated further below)] I think, since we already have the translation of Lam-rim Chen-mo, so the… Thupten Jinpa: …the sections, the specific sections dealing with the ceremony for generating, affirming, our generation of our awakening mind by means of a ceremony— that section maybe, since we already have the translation in English, we could read that section from the translation.

His Holiness: So, instead of repeating after the lama, not necessary to do that. Just read three times. Maybe, I think, worthwhile isn’t it? What do you think? [continues in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: [to the audience] Did you bring volume two? Maybe you didn’t.

His Holiness: Okay. Then the shorter one.

Thupten Jinpa: So in the Heart Sutra, we just heard how the Buddha states that all the buddhas of the past, all the buddhas of the present, and all the buddhas of the future either attained enlightenment, or are attaining enlightenment, or will attain enlightenment on the basis of the engaging in the perfection of wisdom practices. And so the Sutra itself states how it is the perfection of wisdom, the realization of which will lead one to attainment of the full awakening of buddhahood.

So when we talk about the perfection of awakening, the perfection of wisdom, we are talking about a direct realization of emptiness (a wisdom that is a direct realization of emptiness) that is complimented with the factor of bodhicitta, the awakening mind. And so the awakening mind is a very crucial factor for the attainment of buddhahood.

Generally, between the wisdom and bodhicitta, the wisdom of emptiness is a common cause for the attainment of all the three types of enlightenment: the enlightenment of the disciples, enlightenment of the self-enlightened ones, and enlightenment of buddhahood. However, it is the bodhicitta that is the unique condition for attainment of buddhahood.

So without bodhicitta there is simply no possibility of attaining buddhahood. So we have already been speaking about awakening mind, bodhicitta. So most of us have some at least conceptual understanding of what bodhicitta is, what the awakening mind is.

So what we need to do is to try to bring that understanding to our mind and to see if we can have some sense of feeling, accompanied by that understanding. It is not just at the level of understanding, but to have some kind of experiential feeling associated with that understanding.

And then, you know, that kind of experiential flavor that we get, based upon the understanding of the concept of bodhicitta, then that needs to be developed further and further, and enhanced.

And here, one of the methods that is suggested is to reaffirm your generation of the awakening mind by means of participating in a rite. And here it’s known as holding, or seizing, the aspiring awakening mind by means of a ritual, by means of a rite. And this is what is presented in Tsongkhapa’s Lam-rim Chen-mo.

In Lam-rim Chen-mo, the main ceremony is really cited from Asanga’s Bodhisattvabhumi (Bodhisattva Levels), and it is fairly extensive. And so we thought that if you had the text we could have read that section. But since you did not bring that volume, we will forget about reading that section, and do the ceremony on the basis of reciting the three stanzas which I normally do. By the way, the translation is in page 45 of the program, the program booklet.

Visualization and the Seven-Limbed Practice

His Holiness: Firstly, now visualize in front of us Buddha Shakyamuni. Visualize as a living person.

Then, surrounded by bodhisattvas. Those bodhisattvas in the form of deities like Avalokitesvara, Manjusri, Maitreya, Samantabhadra—all these.

Then, most important, Nagarjuna, Arya Asanga, Aryadeva, Vasubandhu. Then the other great Nalanda masters, all now here, visualized.

Then, I think it really worthwhile to imagine, like Nagarjuna, is holding his own—those precious texts—which still we can read. We can study. We can contemplate. As well as Arya Asanga. So then it will become something living.

So then Shantarakshita, Kamalashila, and from that, all those lineages, those Tibetan great masters. And also here, our Chinese brothers and sisters, your own lineage from Indian master, again Nagarjuna, like that. So Japanese tradition, Chinese tradition, Vietnamese tradition—all ultimately same lineage. Then Theravada, again from Buddha and Rangjok, Kashyapa…

Thupten Jinpa: …Subhuti…

His Holiness: …Subhuti, and Ananda…[continues in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: …Katayana.

His Holiness: …these three main Buddha’s disciples who, collection of these three, like that, so visualize all these great masters. Then… [continues in Tibetan]

Now first, the…[continues in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So the first limb is to recall to your mind all the enlightened qualities of the body, speech and mind of the entire assembly of refuge in front of you, including principally the Buddha Shakyamuni and reflecting upon their qualities of body, speech and mind—and particularly their quality of the realization that they possess which is the bodhicitta—the awakening mind, that cherishes others’ welfare as more important than one’s own.

And complemented by that, the realization of emptiness, the ultimate mode of being of all phenomena. Thus the realization embodies a wisdom that is endowed with the essential essence of compassion.

And so imagine, bring these qualities to your mind. And then imagine making prostrations to the assembly.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So the second limb is making offerings. So here you imagine making offerings to the assembly, all the things that you yourself possess and those things which are not possessed by anyone, common objects. You make offerings to the assembly, and particularly you should make the offering of your entire being in the service of all the buddhas and bodhisattvas, those who, right from the beginning, dedicated their lives for bringing about the welfare of infinite numbers of sentient beings.

And so you offer yourself for their service, so that you make a kind of a determination that, “I offer myself so that I may contribute towards the fulfillment of the aspirations of these buddhas and bodhisattvas.”

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So with this also, then you should imagine making offerings to all the buddhas and bodhisattvas—all the virtuous activities that you may have engaged in. Particularly the virtues that you may have accumulated on the basis of even having a slight understanding of the concept of bodhicitta, the awakening mind, and emptiness. And then this is the most important form of offering. Here you are offering your own personal practice and realization.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So next you should make the determination that, “I shall declare and purify all the actions that I may have engaged in that have been harmful to other sentient beings. And particularly those actions that I may have engaged in which have been motivated by self-cherishing thoughts”—a state of mind, an attitude, that shunned the welfare and interest of other sentient beings. And motivated by that sense of obliviousness to others’ welfare, a self-cherishing thought may have led to all forms of activities. So you declare these actions and also purify them from the depth of your heart.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So next is the limb of rejoicing. Here you should bring to your mind all the great enlightened qualities of the body, speech and mind of the buddhas and bodhisattvas and cultivate a deep sense of admiration towards them.

And also you should cultivate a sense of rejoicing and admiration towards all the virtuous and wholesome activities that other sentient beings have engaged in. And including the practices of loving-kindness and compassion and altruistic actions that members of other religious traditions also represent. So develop a deep sense of admiration for all of them and rejoice in them.

And also bring up to your mind all the virtuous actions, wholesome actions, that you may yourself have engaged in, for example, as a result of meditating upon loving-kindness, or bodhicitta, awakening mind, or cultivating the view of emptiness. And as a preliminary towards these, all the actions of body, speech and mind, the virtuous actions that you may have engaged in—bring these to your mind, and cultivate a deep sense of rejoicing in these.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So then the next limb is making a request to all the buddhas and bodhisattvas, particularly the buddhas, to turn the wheel of Dharma in accordance with the needs and mental dispositions and capacities of diverse sentient beings.

And then, on that basis, making an appeal to the buddhas not to enter into final nirvana, but be present.

And finally, the final limb is the dedication. And here you dedicate all your merits and virtuous karma towards the attainment of buddhahood for the sake of all beings so that your merits and virtue are dedicated towards the realization of the welfare of all sentient beings—which is the aspiration of the buddhas.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So these are the seven-limbed practices.

Ceremony for Generating the Awakening Mind

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So for the actual ceremony of generating the awakening mind, at first you should contemplate, reflect, bring to your mind, the following points that Shantideva makes in his Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life, when he states the following.

He states that, “Whatever happiness there is in the world comes about on the basis of the thought cherishing others’ welfare. Whatever problems there are in the world, they come about on the basis of self-cherishing. And what more needs to be said? Simply compare between the Buddha who has cherished others’ welfare and the ordinary beings who have cherished their own welfare.”

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: To summarize the main points that Shantideva is making, he then states the following: “If one does not exchange one’s own happiness with that of the suffering of others, there is no possibility of attainment of buddhahood. And even in the world, there will be no joy.”

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So whether it is on the level of nirvana—transcendence—or whether it is at the level of samsaric everyday existence, in both of these contexts the most precious thing, something that is akin to a jewel, is really this bodhicitta, the awakening mind.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: This precious mind, the awakening mind, bodhicitta, is a quality that we as a human being who possess the human intelligence are capable of cultivating.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: At this juncture today we have attained, obtained, this human existence.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So we should make the determination that, “I shall ensure that this obtainment of human existence is made purposeful, meaningful.”

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: In making this human existence meaningful, there is no more effective way of doing this other than cultivating bodhicitta—the awakening mind.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So for example, Shantideva states in his Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life, where he says that for many eons, “The buddhas, who have contemplated for many eons, have found that this is the most beneficial thing to do.”

His Holiness: So now we are going to determine, “From now on I am going to practice this altruistic mind.” So whenever the possibility is there, serve others. Help others. If not, at least restrain from harming others. We are determined, not only in this life, but life after life, eon to eon. “I am determined now to follow this way.”

Okay.

So I myself also practice that as much as I can. That really brings immense sort of pleasure, immense sort of happiness. And also, how to say, gain much inner strength. So also this is, I think, best offering to Buddha. And not only Buddha. I think best offering to entire sentient beings. So remember that. With that, now repeat.

Thupten Jinpa: So we will now read the three stanzas together three times:

With a wish to free all beings I shall always go for refuge

To the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha

Until I reach full enlightenment.

Enthused by wisdom and compassion,

Today in the Buddha’s presence

I generate the awakening mind

For the benefit of all sentient beings.

As long as space remains,

As long as sentient beings remain,

Until then, may I too remain

And dispel the miseries of the world.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So then, immediately after generating the awakening mind, Shantideva says that, “Today, I have made my human existence meaningful.” And, “I have been born in the family of the buddhas.”

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: And then, “I have become a child of the buddhas.”

His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: And then this is followed by the other following lines, where he says, “From now on I shall never indulge in deeds that are unbecoming of that family. And I shall engage in activities that are becoming of that family. And I shall ensure that this unsullied family is not sullied.”

His Holiness: Now, difficult text…[continues in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So yesterday we were talking about the importance of identifying correctly the object of negation. And this is a very important point. Because if we fail to identify the object of negation (what is being negated) correctly, then although in the context of our meditation we may have some experience of a form of an absence or emptiness, but that emptiness or absence need not necessarily be true emptiness, the final emptiness.

For example, when we meditate on no-self (selflessness of a person), although we may assume that what we are meditating upon is the selflessness of a person in terms of emptiness of inherent existence of the person, but in reality our understanding of that may only remain at the level of the negation of the person in terms of self-sufficient, substantial reality of the person, but may not be the full emptiness of inherent existence of the person.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So another possibility of kind of veering into a different understanding of emptiness is, of course, often in the text emptiness is characterized as the total pacification of conceptual elaboration (as Nagarjuna presents in Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way). So there is the possibility of understanding emptiness, or the ultimate reality, to be the mere pacification of the conceptual elaborations.

And also when you, in the course of understanding emptiness by means of the reasoning process, whether through application of the Diamond Slivers analysis, which examines phenomena from the point of view their causes, or through the reasoning of the absence of identity or difference, which is a reasoning that looks at the phenomenon itself, or a reasoning that examines the phenomenon from the point of view of its effects—whatever forms of reasoning that one employs—as a result, at the end, nothing can be found. Because when we subject phenomena to that kind of analysis, they are all revealed to be untenable, unfindable.

So because of this, there is the possibility that someone might take that to be the ultimate reality. And because the reality, ultimate reality, is this unfindableness, therefore when mind relates to that truth, the way in which it should relate to that truth is to suspend any form of determination, and say that nothing exists. Because nothing can be found, therefore nothing exists. So the mind, when it engages with reality, should do so from… without making any determination. And in fact this is the understanding that Tsongkhapa himself had when he was young, when he was composing for example, his Golden Rosary (a commentary on Abhisamayalankara).

And similarly, the same point, the same position, is presented in Tsongkhapa’s poetic retelling of one of the bodhisattva stories, Tak du ngo. And in that story, Tsongkhapa explains that although all phenomena are illusion-like and they are unfindable, however, for the sake of others’ perspective, one does assume the validity of dependent origination. So in other words he is according validity to the dependent origination world only for the sake of others. So that kind of perspective is there in early writings of Tsongkhapa as well.

And also later in The Three Principal Aspects of the Path, Tsongkhapa explains how, so long as the perspective of dependent origination, which relates to objects at the level of perception (at the level of appearances), and the perspective of emptiness (which relates to phenomena at the level of their ultimate reality) so long as they remain at odds with each other (and the metaphor that is used is like the two feet of a weaver which are never pressed together, they are always kind of alternating)—so long as these two perspectives remain alternating and never really converge—then Tsongkhapa says that, for example, he says that the appearance (which is the infallibility of dependent origination) and emptiness (which is devoid of all forms of propositions or standpoints) so long as these two remain alternate, then until that point, one hasn’t arrived at the final intention of the Buddha.

Dependent Origination and Emptiness (cont.)

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So this dependent origination that Tsongkhapa is talking about (which relates to the appearance level of reality) Nagarjuna explains in the Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way (that we discussed yesterday), where he says that, when identifying the meaning of the term emptiness, he identifies it in terms of the meaning of dependent origination. So he writes in the Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way, he says, “That which is dependently originated, that I describe to be empty.”

So compared to other forms of reasoning, such as Diamond Slivers and so on, when you look at the reasoning of dependent origination, the reasoning of dependent origination does not lead you to a point where it demonstrates that nothing can be found. But rather it demonstrates that thing’s emergence or origination by means of dependence. So in that sense the reasoning of dependent origination has the power to transcend both the extreme of absolutism and also the extremes of nihilism or non-existence.

And this is made even clearer in Nagarjuna’s Precious Garland, where he writes the following. He says that, “The person is neither the earth element nor the water element” and so on. “Nor is it the consciousness,” and then “However, where is the person over and above these elements?” Then the question is raised.

Then immediately after that, Nagarjuna does not then give us the conclusion, ‘Therefore the person is devoid of inherent existence.’ Rather, he provides an intermediate line where he says that, “The person exists in relation to the collection, aggregation, of the six elements.” And then having said that, then he says, “Therefore it possesses no final reality.”

So what Nagarjuna does is, he does not jump straight from the unfindability of the person (when you subject it to critical analysis) to emptiness. But rather, having revealed the unfindability of the person when subjected to critical analysis, he then brings up the understanding of dependent origination—that the person does exist. So it rejects the notion of total non-existence of the person and then, because the existence of the person is understood by means of dependence, therefore the person is devoid of any final reality of its own or inherent existence.

And this is also made very clear in Chandrakirti’s Entrance to the Middle Way, where he says that, “The person does not exist….The person cannot be found, when subject to sevenfold analysis, both on the conventional level (both in worldly terms) nor in terms of its reality. However, without such critical analysis and on the level of worldly convention, the identity of the person is posited. And therefore the person…” sorry, he is talking about the chariot, “…therefore the chariot is dependently designated in relation to its various components.” And in this way Chandrakirti also explains the meaning of emptiness to be that of absence of inherent existence, any form of existence grounded in its own reality.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So in this regard we will read from Tsongkhapa’s text. This is Volume 3 on page 132, the first paragraph, when he writes the following: “The twenty-sixth chapter of Nagarjuna’s Fundamental Wisdom teaches the stages of production in the forward progression of the twelve factors of dependent origination and the stages of their cessation in the reverse progression. The other twenty-five chapters mainly refute…”

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So in fact this is the reason…

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So in fact this is the reason why, when I teach Nagarjuna’s Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way, I begin with the twenty-sixth chapter, because the twenty-sixth chapter presents the teaching on dependent origination in terms of cause and effect, particularly within the framework of the twelve links of dependent origination. By doing so, then you establish the basis—which is the understanding of the law of cause and effect—and also provide an understanding of the basis upon which emptiness can then be established.

And this is also in the spirit of Nagarjuna himself when he writes in the Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way, where he says that, “Without reliance upon the convention, the ultimate cannot be realized.” Similarly Chandrakirti states in The Entrance to the Middle Way that, “The conventional truth,” the truth of worldly convention, “is the means and the ultimate truth is” the fact derived through such a means, “arrived at through such a means.”

So when you present the understanding of dependent origination in terms of cause and effect, then you can utilize that as the premise and the rationale for then moving on to understanding of the emptiness of inherent existence, intrinsic existence.

So Tsongkhapa writes in the text we read, “The other twenty-five chapters mainly refute intrinsic existence. The twenty-fourth chapter analyzes the four noble truths. It demonstrates at length that none of the teachings about cyclic existence and nirvana— arising, disintegration, etc.—make sense in the context of non-emptiness of inherent existence, and how all of those do make sense within the context of emptiness of intrinsic existence. Hence, you must know how to carry the implications of this twenty-fourth chapter over to other chapters,” as well.

“Therefore, those who currently claim to teach the meaning of the Middle Way are actually giving the position of the essentialists when they hold that all causes and effects—such as the agents and objects of production—are impossible in the absence of intrinsic existence. Thus, Nagarjuna the Protector holds that one must seek the emptiness of intrinsic existence and the middle way on the very basis of the teachings of cause and effect—that is, the production and cessation of specific effects,” (the arising and cessation of this and that effect) “in dependence upon…” (this and that condition). “The twenty-fourth chapter of Nagarjuna…”

Then Tsongkhapa cites from Nagarjuna, the passage that we already cited, “That which is dependently originated, this I explain…I describe as emptiness.”

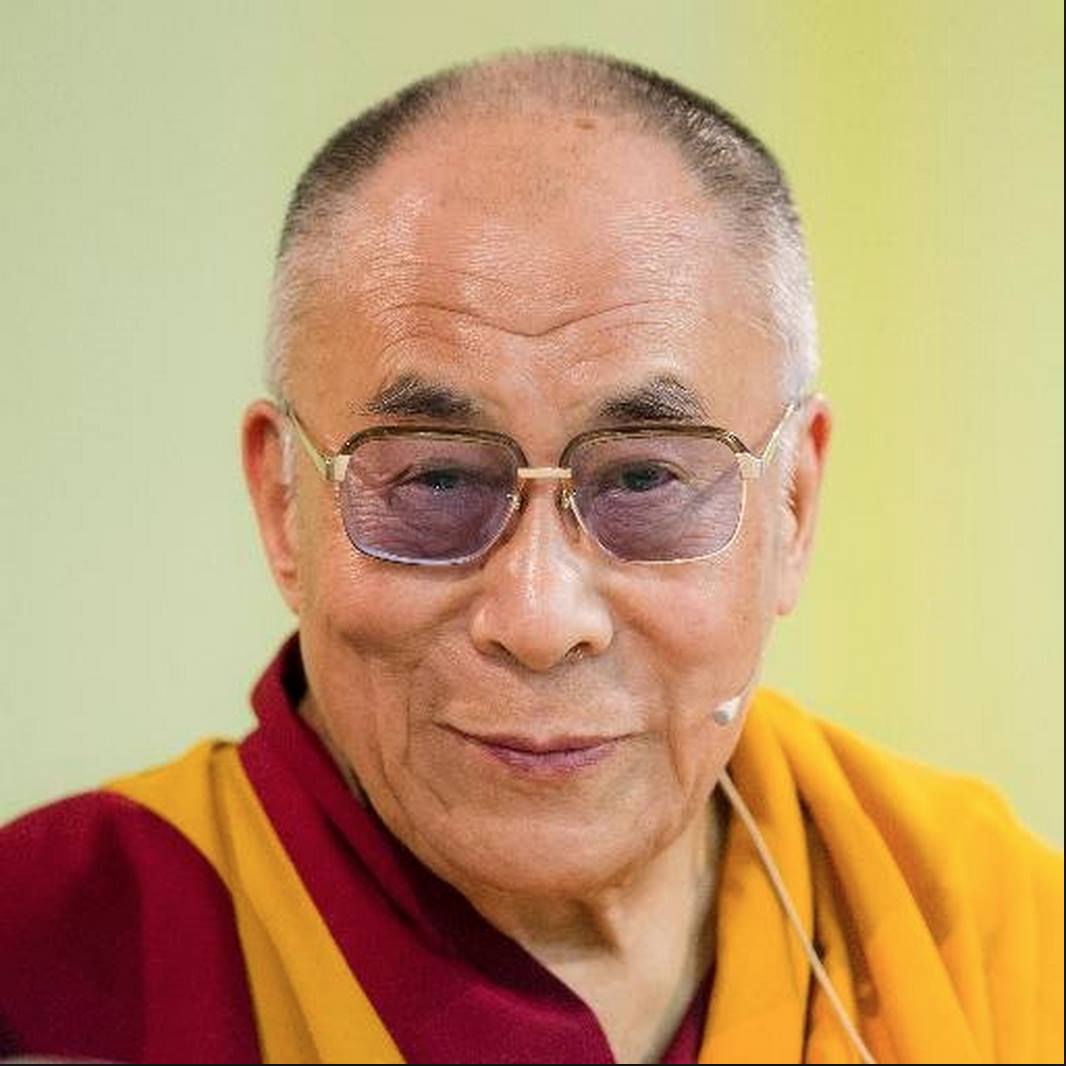

In July 2008, His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama gave a historic six-day teaching on The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment (Lam-rim Chen-mo), Tsongkhapa’s classic text on the stages of spiritual evolution. Translator for His Holiness was Thupten Jinpa, Ph.D.

This event at Lehigh University, Pennsylvania, marked the culmination of a 12-year effort by the Tibetan Buddhist Learning Center (TBLC), New Jersey, to translate the Great Treatise into English.

These transcripts were kindly provided to LYWA by the Tibetan Buddhist Learning Center, which holds the copyright. The audio files are available from the Tibetan Buddhist Learning Center’s Resources and Linkspage.

The transcripts have been published in a wonderful book, From Here to Enlightenment, edited by Guy Newland and published by Shambhala Publications. We encourage you to buy the book from your local Dharma center, bookstore, or directly from Shambhala. It is available in both hardcover and as an ebook from Amazon, Apple, B&N, Google, and Kobo.

http://www.lamayeshe.com/article/chapter/day-six-morning-session-july-15-2008