His Holiness the Dalai Lama: Tsongkhapa then writes: “How does one determine whether something exists conventionally?”

16 His Holiness the Dalai Lama: Teachings on Lam-rim Chen-mo

Day Six, Morning Session, July 15, 2008 at Lehigh University, Pennsylvania, USA. Part two. The Two Truths and the Four Noble Truths. Finding the Middle Way: Analysis Refutes Intrinsic Nature. Svatantrika School and Intrinsic Existence. Conventional Knowledge.

The Two Truths and the Four Noble Truths

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So this actually points towards the important understanding that it is when you have a developed understanding of the two truths, then you have the basis for a deeper understanding of the significance for the four noble truths. We already discussed that earlier.

So for example, Tsongkhapa here writes on page 135, second paragraph, he says that, “This being the case,” (he is referring to the understanding of emptiness in terms of intrinsic existence) he says that, “…dependent origination is tenable within emptiness of intrinsic existence, and when dependent-arising is tenable, suffering is also tenable—for suffering may be attributed only to what arises in dependence on causes and conditions.”

So in other words Tsongkhapa is making the connection that once it becomes possible for you to maintain an understanding of ultimate reality in terms of emptiness of intrinsic existence, this then enables you to understand dependent origination. When dependent origination becomes tenable then the notion of suffering becomes tenable because suffering is a dependently arisen, causal phenomenon. And when suffering becomes tenable, understandable, then the origin of suffering becomes understandable. And among the origins of the suffering, the root really is the ignorance with relation to the ultimate nature of reality. So because of this, one also, as explained before, comes to the understanding of the possibility of its cessation.

So when you understand the possibility of its cessation then you will also understand the possibility of a path that would lead to that cessation. And path, true path, and that cessation together constitute what we call the true Dharma, the Dharma jewel. And when the Dharma jewel becomes tenable, possible, then one can also envision an individual who can embody that Dharma, and that person would be the Sangha. And if there is a Sangha then the perfection of that Sangha would be the Buddha.

So in this way, the four noble truths become tenable and also the three jewels become tenable. So we can see how, when you understand the relationship between the understanding of the two truths and the four noble truths, then the entire mode of procedure of the Buddhist path becomes clear.

Finding the Middle Way: Analysis Refutes Intrinsic Nature

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So the next major outline that we will be dealing with is…

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So in the next major outline we read from page 156 here… sorry, it starts from page 155, where the main outline that Tsongkhapa is discussing now is, “Showing that the Madhyamaka critique does not eradicate conventional existence.”

So within this, we read (from page 156, the first para) where Tsongkhapa writes: “A proper analysis of whether these phenomena, forms and so on, exist, or are produced, in an objective sense is what we call ‘a line of reasoning that analyzes reality,’ or ‘a line of reasoning that analyzes the final status of being.’ Since we Madhyamikas do not assert that the production of forms…” (and so on or the arising of forms and so on) “…can withstand analysis by such reasoning, our position avoids the fallacy that there are truly existent things.”

“…If these things cannot withstand rational analysis, then how is it possible for something to exist when reason has refuted it?”

So that is the question, and the reply that is given is, “You are mistakenly conflating the inability to withstand rational analysis with invalidation by reason.”

So this is an important point that Tsongkhapa is making—the distinction between something that is incapable of withstanding critical analysis and something that is proven to be invalidated by that critical analysis. So in other words he is saying that, for example, when we subject things like arising and so on to critical analysis by means of analyzing whether things come into being from themselves or from others and so on, then already we are entering a domain of analysis that is really an ultimate form of analysis.

And since the existence of things is not posited from the ultimate standpoint, Tsongkhapa is saying that… so these arisings and so on—facts—cannot withstand ultimate analysis. And the fact that they cannot withstand ultimate analysis is not the same as ultimate analysis somehow invalidates them or negates them. So one should be able to make a distinction between that which is negated by reason and that which is not found through that critical reasoning.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: And here… and this is made clear. For example yesterday we cited from Gung-tang Rimpoche when he says that, “In the context of the philosophical view of emptiness, because we are searching for the intrinsic nature, so in that context, when we do not find that intrinsic nature, this constitutes the negation of intrinsic nature.”

Reliable Means of Knowledge8

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So the next outline that we will look at is the second one, which is: you cannot eradicate conventional phenomena by refuting them through investigating whether valid cognition establishes them or not.

So here the main point being made is whether Nagarjuna’s standpoint, or Nagarjuna’s system, accepts any notion of valid cognition. And for example, there are citations from the sutra where… which state that the eyes, the nose, and the ears, are not valid cognitions. And here Tsongkhapa explains that these statements in the sutras are not rejecting valid cognitions in general but rather…

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So in fact immediately after the statement of this line where eyes… the sensory perceptions are not to be taken as valid cognitions, in Chandrakirti’s Entering the Middle Way, he then follows that up by saying that if these are valid cognitions then what need is there for the minds of the…

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So this is actually in the sutra where it says that if these sensory perceptions are valid, then what need is there for the paths of the noble beings, arya beings, and their perspectives? So the subsequent lines already explained suggest clearly in what context the notion of valid cognition is being negated here and in relation to what the valid cognition is being negated here.

So Tsongkhapa explains that these statements in the sutra do not reject the notion of valid cognition in general, but rather reject the validity of the sensory perceptions in relation to the ultimate nature of things, because it is the perspective of the arya noble beings, whose cognitions are valid when it comes to the ultimate mode of…ultimate reality of things.

And so if you look at the sensory experiences, the sensory perceptions, even at the perceptual level there is an appearance of things as possessing some kind of inherent existence. So on that level there is an element of deception. There is an element of an error, but that does not mean that these perceptions are somehow totally invalid. They may be erroneous at the level of their perceptions, but that does not mean they are totally invalid.

And also in Nagarjuna’s own writing, we find mentions of at least four different classes of valid cognition. He speaks of direct perception as a form of valid cognition, inferential cognition, cognition based upon testimony, and cognition based upon analogy, analogical cognition.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So this analogical… or cognition in the form of analogy is sometimes also referred to as cognition derived from perception of likeness, similarity.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So in general, in fact all forms of valid cognition can be subsumed into the two classes: one is the direct perception; and the inferential cognition. So for specific… because of their specific functions, the valid cognition based on testimony, or testimonial cognition, or analogical cognitions, are listed separately because of their specific functions. Because the immediate kind of premise that gave rise to these valid cognitions are either analogy, analogical reasoning, or reasoning based on testimony, but indirectly they are also a form of inferential cognition.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: And then there is, on page 164, Tsongkhapa cites from Chandrakirti’s Commentary on the “Four Hundred Stanzas on the Middle Way,” and then on page 165 he then comments upon this in the following: “How do you interpret this general refutation of the position that visual consciousnesses and such are valid cognitions?”

And then in response Tsongkhapa writes, “Unlike the passage ‘Eye, ear, and nose are not valid,’ this passage has been a source of grave doubt. Therefore, I will explain it in detail.”

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So in commenting upon this particular statement from Chandrakirti’s Commentary on the “Four Hundred Stanzas” then Tsongkhapa goes on to write that (this is on page 165): “As we will explain,…” this is the last paragraph, second to last, “…the master Chandrakirti does not accept even conventionally that anything exists essentially or by way of its intrinsic character. Thus, how could he accept this claim that the sensory consciousnesses are valid with regard to the intrinsic character of their objects? Therefore, this refutation of the claim that the sensory consciousnesses are valid is a refutation of the view that they are valid with regard to the intrinsic character of the five objects.”

So Chandrakirti… commenting upon Chandrakirti here, what Tsongkhapa is explaining is that when we talk about a certain perception or perspective as being erroneous or invalid or deceptive, I think we have to understand—in relation to what? And also for example, generally speaking (at the level of conceptual thought) the understanding is that even the realization of emptiness, at least with relation to the kind of appearance, on the level of appearance, even there, there is an element of distortion, there is an element of error. However, with relation to the actual object that is being comprehended, then it is valid. So one needs to make a distinction between the mode of apprehension of something and the way in which that object is perceived. So the perceptual level and the comprehension or apprehension level.

However here Chandrakirti is really negating the notion of valid cognition proposed by other masters like Bhavaviveka for whom, when they say that sensory perceptions such as visual experiences, auditory and so on are valid with relation to their objects, they are also claiming that they are valid in relation to the intrinsic nature of these objects as well, rang tsen, which is svalakshana.

So what Chandrakirti is pointing out is that even with relation to the intrinsic character of the object that they are perceiving, they are erroneous, because when they perceive the objects, they perceive the objects to possess an objective, inherent existence.

However, the content of that perception, which is the inherent existence of the object, is untenable. Because, if it is the case that they do possess reality, then when we subject them to critical analysis and seek their essence and seek their intrinsic nature, that intrinsic nature should become clearer and clearer—more obvious.

And here, for example, Nagarjuna in his Precious Garland gives the analogy that if a mirage is truly water, then the closer you get to it the more obvious the water should become. However, the closer you get to it the perception of water begins to dissolve. Similarly, if intrinsic natures that we perceive in the objects do truly exist, then the more we search for them the clearer they should become to our mind—which is not the case.

So in this way, Chandrakirti points out that even our visual and sensory perceptions are erroneous when it comes to the intrinsic nature of the objects themselves, because the objects do not possess the intrinsic nature (as our visual sense perceptions tend to perceive). So in this way, what Chandrakirti is pointing out is that there is a disparity or a gap between the way we perceive objects and the way objects truly exist or really are. And because of this disparity or gap there is an element of distortion—there is an element of invalidity in our perception.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: Sorry, actually, I forgot something. So in fact just as we… At the level of our sensory perceptions, we perceive things and objects to possess some kind of intrinsic nature. And it is on that basis of our perception, we then assume they possess this objective, inherent existence. And in fact it is this very perception of reality of the intrinsic-ness which we use as a rationale for believing in their objective, inherent existence.

For example, the Mind Only School, when they propound the notion of arising from another, other factors, they say that, “We don’t need to establish the validity of the notion of arising from other because arising from other factors is something that we can directly perceive.” And so what they are presenting is the very fact of something that we perceive as being the basis for their possessing intrinsic nature.

So, and then to read further from Tsongkhapa’s text, so then he writes on p. 165, the last para: “This refutation is made by way of the Bhagavan’s” (the Blessed One’s) “…statement that consciousness is false and deceptive. The statement that it is deceptive refutes its being non-deceptive, and this in turn refutes its validity because ‘that which is non-deceptive’ is the definition of ‘valid cognition.’ In what sense is it deceptive? As Chandrakirti puts it, ‘it exists in one way but appears in another.’ ” (So here, pointing out about the disparity between the perception and reality) “This means that the five objects—forms, sounds, and so forth—are not established by way of their intrinsic character, but appear to the sensory consciousnesses as though they were. Therefore, those sensory consciousnesses are not valid with regard to the intrinsic character of their objects.”

And then he continues: “In brief, what Chandrakirti intended in this passage is that the sensory consciousnesses are not valid with regard to the intrinsic character of the five objects because they are deceived in relation to the appearance of intrinsic character in the five objects. This is because those five objects are empty of intrinsic character yet appear to have it. For example, it is like a consciousness that perceives…” a double moon.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: And then Tsongkhapa makes a kind of a concluding statement. He says: “Therefore because these statements negate the sensory perceptions and so on, as being valid with respect to the intrinsic nature, therefore, they do not negate these perceptions as being invalid… negate these perceptions as being valid in general.”

So therefore these statements do not negate the conventional cognitions as being valid in general.

Svatantrika School and Intrinsic Existence

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: Then the question is how do we… on what basis can we infer that the master Bhavaviveka actually subscribes to the notion of intrinsic existence, existence by means of svalakshana, self-defining characteristics?

So here, one could cite two examples. One is the well-known statement from Blaze of Reasoning (which is an auto-commentary on his text, Essence of the Middle Way) where Bhavaviveka says that, “In our case we accept the sixth mental consciousness to be the true referent of the term ‘person.’ ” So the implication is that he accepts identity of a person that can be found when you search for the true referent of the term ‘person.’

Secondly, Tsongkhapa points out here (in Bhavaviveka’s commentary on Nagarjuna’s text, Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way)—Bhavaviveka in negating or in refuting the Mind Only position vis-a-vis the interpretation of the Perfection of Wisdom sutra.

Mind Only School interprets the Buddha’s turning of the wheel in the following manner. For them the first turning of the wheel of the Dharma is non-definitive. And the second turning of the wheel of Dharma, although its content is definitive, which is emptiness, however, this is a sutra that should not be read on the literal level. Because on the literal level the second turning of the wheel of Dharma, the Perfection of Wisdom sutras, negate intrinsic existence across the board—from form (in the list of enumeration) from form to the omniscient mind of the Buddha.

So on the literal level, although the sutra negates intrinsic existence across the entire spectrum of phenomena, the Mind Only School argues that this sutra needs to be interpreted on the basis of the Samdinirmochana Sutra (Sutra Unraveling the Intent of the Buddha), the third turning.

So therefore when we read the Perfection of Wisdom sutra, we read the negation contextually by identifying different natures of phenomena. So they speak in terms of imputed phenomena…sorry, the imputed nature, the dependent nature, and the consummate or ultimate nature. And so when Buddha states in the Perfection of Wisdom sutra that all phenomena are devoid of intrinsic existence and identity, this identityless¬ness of phenomena is understood contextually in relation to dependent phenomena, imputed phenomena, and the ultimate phenomena.

So with relation to the dependent phenomena, what is being negated is intrinsic arising, or ultimate arising; and with relation to imputed phenomena, intrinsic existence is negated (or existence by means of self-defining characteristics is negated); and with relation to the ultimate or consummate nature, existence by means of ultimate mode of being is negated. So in this way they contextually interpret the Buddha’s teaching on emptiness as presented in the Perfection of Wisdom sutra.

In commenting upon this, Bhavaviveka states that if your statement [is] that the imputed phenomena are devoid of existence by means of self-defining characteristics, then when you say ‘imputed phenomena’ we can analyze that in terms of ‘that which imputes’ and ‘that which is imputed’.

And if you reject intrinsic existence to ‘that which imputes’ then you are talking about language and concepts, because it is the language and concepts that impute characteristics. So if you reject language and concepts to possess inherent existence, then you will be falling into an extreme of nihilism.

So by making that allegation or accusation, Bhavaviveka,… the implication is that Bhavaviveka himself accepts intrinsic existence to language, concepts and so on, conceptual thoughts and so on.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So similarly…

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So similarly Kamalashila, when commenting upon the Samdinirmochana Sutra, he qualifies all the negation with a caveat that, ‘in the ultimate’, ‘from the ultimate point of view,’ or ‘on the ultimate level’. So Kamalashila also explains that it is the Samdinirmochana Sutra, this Unravelling the Intent of the Buddha, that establishes the definitive reading of the scriptures. So in other words, Kamalashila also accepts theSamdinirmochana Sutra to represent a definitive sutra. So this implies that both Kamalashila and Shantarakshita also subscribe to the notion of svabhav or svalakshana. His Holiness: [in Tibetan]

Thupten Jinpa: So in this way we understand that, among the Middle Way thinkers, there were two camps: one camp that accepts the notion of svalakshana on the conventional level, existence by means of self-defining characteristics; and another camp that rejects the notion even on the conventional level.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So then later there is a section in the text where also Tsongkhapa points out Bhavaviveka’s position vis-a-vis the concept of atomic structure of material things. And he makes distinctions between aggregation and collection and also teases out that Bhavaviveka’s position represents some form of acceptance of intrinsic nature.

Of course these sections are very difficult, quite tough. So, and then there is an expression that when it comes to reading, you know, the more difficult sections of the text, you should be like an old man without teeth trying to eat something.

So when you cannot bite, you just swallow it. So for me also these sections would be very difficult. But for you also maybe even more difficult. So we will skip those sections.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So, when we come to that kind of part of the text, then it’s better to kind of give a little time off for both the teacher and the student.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: Then Tsongkhapa then talks about, “If our perception of everyday objects is erroneous with respect to intrinsic nature of things, then how is it that they are referred to as conventionally true?” So here Tsongkhapa is explaining what is meant… the meaning of the truth in the context of conventional truth and ultimate truth.

He explains that when we use the word ‘truth’ in the context of conventional truth, ‘truth’ here does not have a connotation of objectivity but rather truth from the perspective of the subjective mind. So in this way, therefore, calling a conventional truth a ‘truth’ does not imply the acceptance of some kind of objective intrinsic-ness to the phenomenon.

And then Tsongkhapa goes on to explain that, if we fail to recognize, identify, the object of negation correctly, and then understand, falsely understand, that all the reasoning that negates, the critical analysis,… the reasoning that negates intrinsic nature even on the conventional level—if we come to understand that these reasonings undermine all the validity of everyday transactions and conventions—then one will fall into a position where no distinction can be made between a correct view and an incorrect view, and where both of them will be either false or either true. And therefore one will fall into a standpoint that would represent a grave, erroneous view.

And then he writes: “As a result, prolonged habituation to such a view does not…” (this is on page 178, second para), “As a result, prolonged habituation to such a view does not bring you the least bit closer to the correct view. In fact it takes you further away from it, for such a wrong view stands in stark contradiction to the path of dependent origination, the path in which all of the teachings on dependent origination of cyclic existence and nirvana are tenable within our system.”

Then Tsongkhapa cites from Chandrakirti and then… So the question is how do we then understand that if our perception of all phenomena as possessing intrinsic nature is erroneous—they do not possess any objective inherent existence—then how do we adjudicate what is correct and what is incorrect understanding? So for example between… And the question then becomes, “Does that mean that anything that the mind creates becomes real?”

And so if that is the case then, with relation to the horn on a rabbit’s head, a rabbit horn, we can have a thought of that, and the thought of the rabbit’s horn actually conjures the image of a rabbit’s horn, but that doesn’t make the rabbit’s horn to be real.

Similarly the question is how do we adjudicate between the following two perceptions– one false and one correct? So for example, on the basis of a coiled rope, if someone instinctively feels there is a snake there, that perception, based upon the seeing of the coiled rope, is false. However, on the basis of the body of a real snake one can also have the perception of a snake there.

Now in so far as the perceptions of inherent existence of the objects existing in their own right, outside, is concerned…

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So, in so far as the fact that, on the basis of the coiled rope, the snake does not exist in and of itself, and also on the basis of the snake’s aggregates (the body), on the part of the aggregates, there is no intrinsically real snake, so in so far as that fact is concerned, they are both exactly the same. However, one perception is erroneous, incorrect, and the other perception is a correct perception.

So the question is, how do we adjudicate between these two forms of perception? Because, although we can only accord nominal existence to all phenomena—but that does not mean that anything goes—that the reality equates with our concepts.

So here Tsongkhapa then writes: “How does one determine whether something exists conventionally?” (This is on page 178, third para): “We hold that something exists conventionally (1) if it is known to a conventional consciousness; (2) if no other conventional, valid cognition contradicts its being as it is thus known; and (3) if reason that accurately analyzes reality—that is,” that which “…analyzes whether something intrinsically exists—” or not “does not contradict it. We hold that what fails to meet those criteria does not exist.”

So he provides the criteria by which one can adjudicate a form of perception that is false and a perception that is correct.

His Holiness: [in Tibetan] Thupten Jinpa: So although nothing possesses inherent existence, but there is still, at the level of everyday experience, harm and… benefits and harm.

So that means we need to go and eat!

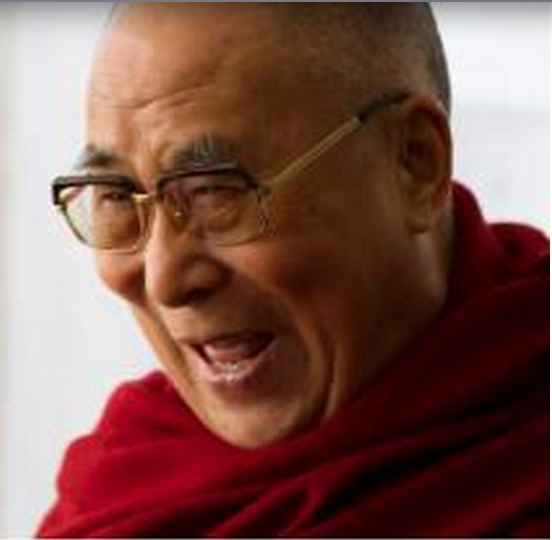

In July 2008, His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama gave a historic six-day teaching on The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment (Lam-rim Chen-mo), Tsongkhapa’s classic text on the stages of spiritual evolution. Translator for His Holiness was Thupten Jinpa, Ph.D.

This event at Lehigh University, Pennsylvania, marked the culmination of a 12-year effort by the Tibetan Buddhist Learning Center (TBLC), New Jersey, to translate the Great Treatise into English.

These transcripts were kindly provided to LYWA by the Tibetan Buddhist Learning Center, which holds the copyright. The audio files are available from the Tibetan Buddhist Learning Center’s Resources and Linkspage.

The transcripts have been published in a wonderful book, From Here to Enlightenment, edited by Guy Newland and published by Shambhala Publications. We encourage you to buy the book from your local Dharma center, bookstore, or directly from Shambhala. It is available in both hardcover and as an ebook from Amazon, Apple, B&N, Google, and Kobo.

http://www.lamayeshe.com/article/chapter/day-six-morning-session-july-15-2008