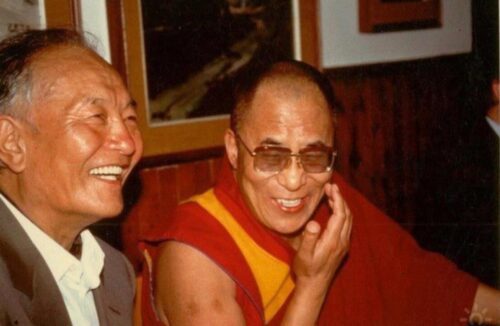

His Holiness the Dalai Lama con Chögyal Namkhai Norbu: “If the teachings are being explained intellectually, that which is being communicated is not intellectual.”

No one will be realized or enlightened just by studying the concepts of the mind. One has to find oneself in the state of knowledge, and really make this knowledge concrete. Buddha said, “I have found a knowledge that is very profound and very enlightened, a very peaceful state, beyond all concepts. And when I communicate this to others they do not understand”. This is knowledge, not something that is analyzed on the level of logic. I am not saying that logical terms have no use but it depends.

From the beginning, Dzogchen teachings have been explained in many ways by the masters. There are intellectual ways and then the symbolic way, which is connected with the tantric style. There is also the direct method: from knowledge directly to knowledge. This is what is called the transmission of the knowledge of realized beings.

It is essential to understand that even if the teachings are being explained intellectually, that which is being communicated is not intellectual. And if you do not succeed in transmitting this knowledge, everything just becomes dry words. Many people have a kind of conviction that they have some kind of knowledge. When I met my Master Changchub Dorje, I was really convinced that I had a lot of knowledge, especially of the Buddhist teachings. I did not think of myself as someone who was very stupid. When I met my Master for the first time, I had a lot of pride, because when my Master was teaching he was speaking to people who were not very educated. I was a bit blown up and thought, well, I know the sutras, the tantras and Buddhist philosophy. I really believed this was the meaning of the teachings.

Many people have this kind of attitude and think that they really do know something. But you have to understand what knowledge means. A good example of this was when Manjushrimitra met Garab Dorje. Manjushrimitra was one of the greatest scholars of that period in India and the principal guide of the Yogācāra school. He was considered the supreme Pandit.

When they heard that Garab Dorje was giving a teaching that went beyond the law of cause and effect, the Buddhists became very worried. The Buddhist teachings, especially the sutras, are based on the principle of cause and effect so, of course, it is strange when somebody talks about going beyond cause and effect. Many scholars and pandits felt that they had to go and see Garab Dorje and find out what was going on. As a famous proverb says, “If there is a small fire, it is best to put it out right away. Otherwise it will develop and you will not be able to put it out anymore.”

There was this young Garab Dorje explaining this teaching that was a little different and Manjushrimitra and other scholars went from India to Oddiyana to see him. It was a very long journey in those days, and they made a great sacrifice to undertake it. When they arrived in Oddiyana they began a discussion with Garab Dorje. Manjushrimitra went first, convinced that he had the most knowledge of a certain kind. After they had exchanged a few words, Manjushrimitra immediately understood what Garab Dorje was communicating. And he understood that what Garab Dorje was teaching was the finality, the point of arrival of all the sutra teachings. Manjushrimitra became upset and asked to be excused because he realized that Garab Dorje was not some ordinary intellectual, but that he was an emanation. So Manjushrimitra became the first and also the most important of Garab Dorje’s disciples. He did not need to study or spend many years with Garab Dorje, but all the years of philosophy and study he had done until this time had been a preparation for the moment of meeting Garab Dorje and the communication of the realized state. So, right away, he became a great master of Dzogchen. Thus you can see, there exists this method of communicating intellectually. Manjushrimitra said, “You are a Nirmanakaya emanation and I had this very bad intention when I came here. How can I purify this?”. Garab Dorje said, “Do not worry about this at all. You are a scholar and a Buddhist philosopher, you can communicate this knowledge in the way that you have learned until now.”

So Manjushrimitra wrote a text called Dola Sershung. Dola means like a stone. Usually we have a vision that is pure or impure. When one understands the meaning of the teachings one discovers that the stone is actually gold and this pure gold represents the dimension of every individual. In the Dzogchen teachings we say that our state is self-perfected from the very beginning. What is self-perfected is our infinite potentiality but we do not have this understanding, this knowledge. If we do not have this knowledge, then we see the stone as a stone, and not pure gold. Manjushrimitra explained Dzogchen perfectly in the terms of Yogācāra Buddhist philosophy. Many scholars say these Dzogchen teachings seem to be in Yogācāra style. This is because Manjushrimitra used the Yogācāra terms to transmit the teachings. He became one of the fundamental teachers of Dzogchen and put together all the collection of Garab Dorje’s teachings. When we speak of Dzogchen semde, sem (sems) means mind. This is an abbreviation for what we call Changchub Sem. Changchub Sem means bodhicitta in Sanskrit but not the same bodhicitta meant in the sutras.

In the sutric bodhicitta there are two aspects: absolute and relative. Absolute bodhicitta means the knowledge or understanding of real emptiness. Relative bodhicitta is explained in two ways: the first is our intention and the second its application. When we do a practice, we say that we cultivate bodhicitta. This is the bodhicitta that is the intention. In the Mahayana sutras, bodhicitta is considered to be fundamental. Through this intention we can govern our attitude, our behavior. At the base of the Hinayana teachings there is the Vinaya, which is based on laws. If we receive a vow, behind this vow is law, which has to be applied. We use these vows if our capacity, our character, is not strong, and we want to control our behavior and not commit any negativities.

In Dzogchen, we try to become responsible for ourselves but for the majority of people it does not happen like this. Understanding the basic weakness of the human condition, Buddha clearly explained the Hinayana style, so if we cannot govern ourselves, we have a law that limits our behavior. Therefore, we can understand why a vow exists in the sutra teaching and should not consider a vow as something that is not valid. It is something to adopt and use. We have all kinds of teachings with different characteristics. If we are Dzogchen practitioners, then we have to have awareness, awareness of ourselves and also of circumstances and the relationship between the two. If we have an awareness of this, then we have an awareness of all the aspects of the teachings. So, practicing Dzogchen means to practice Hinayana and Mahayana. It means to look for the essence of all teachings and to live in this essence.

Certainly, we cannot go following all different kinds of specific rules. For example, the fundamental thing in Mahayana is intention, which is much more important than a rule. If there is a good intention and something negative happens, this can have a good result. Intention is considered very important. When we speak of bodhicitta, the first thing mentioned is intention. In life, in every circumstance, we can observe what kind of intention we have. If we are present in our intention, then we do not have to follow rules and everything works out.

We have the intention not to create any negativities. To commit a negative action, first we must have the intention. Also, the conditions for producing negative karma mean that first we have to have a bad intention, then enter into the action, conclude the action, and that becomes a negative force.

Even if we have this evil intention and enter into the action, if we do not conclude the action, then there is something missing for a negative karma. Not only on the level of philosophy, but in law, one says that a crime is premeditated. Someone who has done something intentionally is guilty. Karma is also made in this way.

If we are walking outside and we crush an insect under our feet, it dies. When it dies, it suffers. Whether the person deliberately crushes the insect or not, it suffers just the same. Certainly, it is not positive. A negative action means we produce suffering for other beings.

If we go there with the intention to kill that being, that is different. We are not just talking about a negative action, we are talking about producing a negative karma; a potentiality of karma. The force and potentiality of this negative karma can produce a result. This is what we call cause and effect. When there is a negative cause and then a secondary cause is present for that cause, then it produces an effect.

When we produce this potentiality of negative karma, we certainly do not see anything concrete. This is connected with our condition. When the secondary cause is present this karma manifests itself. I will give an example. Karma is like a shadow. We have a physical body and when there is the secondary cause of the sun, the shadow arises. Why? Because we have a body. But when there is no secondary cause, the shadow does not manifest, as if it never existed.

It is the same with all those negative karmas that are associated with us. Until the secondary causes manifest, they do not appear. It means that when we have all these different kinds of causes, the consequences of them manifest as samsara. First of all, this potentiality can only be manifested if we have the intention. Intention is related to action, whether it is direct or indirect, and at the end when one is satisfied with what one has done and these three qualifications are present, a perfect karma is produced which will have some kind of result.

That is why in the Mahayana intention is very important. We must observe our intention well. Above all, the first thing we do when we do a practice is refuge and bodhicitta. We observe our motive and see why we are doing this practice. If we do not have a good intention, we can change it right away and it becomes a good intention. At least, in the moment of practice, we do this. It is also a good example for life. We do not need to restrict our good intentions to periods of practice.

When we are practitioners of Dzogchen, we try not to be distracted, but to be present. When we are present, we can observe our intention. If we have an evil intention, we immediately become aware of it and can change it. We can cultivate a good intention instead. At least, we can realize that this bad intention may produce a very negative result. If we are present like that, how can negativity arise? This is a good way of regulating our attitude or behavior in life. That is why in Mahayana, intention is more important than applying any kind of rule.

Then we might think, “Oh, I will practice Mahayana because I do not believe in rules”. People are very narrow-minded. They think it has to be one thing or the other. We have to live with more space and give our mind more space.

So, try and apply this principle of Mahayana and Hinayana. If a rule has some sense and it is useful, certainly, we can apply it. The finality of Hinayana is to renounce disturbing other beings. This is the principle aim of that vow. Even if we have no vow, we should keep this vow present. I know that by insulting a person I create suffering for them, because when it happens to me, I suffer. So, in the sutra, we say that we can take an example from ourselves. Buddha taught this in the sutras and it is something very practical and concrete.

In addition, we can teach our children by explaining that they should not kill an insect because they cause terrible suffering for the insect and that the insect could be a mother or father and the children will wonder where their mother or father is. When the child becomes sensitive to that, they will not want to kill insects anymore.

We have many experiences in life like that. If someone does something that is pleasing to me, and I do something pleasing for that person, then they are very happy. If we do not care about others, we are considered very much of an egoist. Above all, it is important to put ourselves in the position of others. In the Mahayana, there are many kinds of trainings in which we mentally change our position with another. If we see a person who is suffering terribly and we try to imagine ourselves in his or her position, then we can understand how he suffers. With this practice, a person becomes more sensitive. It often seems that many practitioners’ sensitivity diminishes and we become like stones. This is very negative. Why does this happen? Because we do not observe ourselves and do not see it happening. In Dzogchen we have to understand the essence of all teachings and integrate them. So remember the principle of Hinayana and do not create problems for others. We should control our own existence, our body, our voice and our mind. This is a vow created by oneself and to apply this is very useful.

The principle of Mahayana is bodhicitta. The first principle of bodhicitta is intention, and then applying it. That is why we speak of application and intention in the Mahayana sutras.

We say, “I want to realize myself for the sake of others.” When one creates this intention this is called cultivating bodhicitta. Basically it is [having] a good thought through which one can accumulate merit. But, if it is only this and nothing very concrete happens, it is because after having the intention we have to apply it, it has to go into action. With negative karma, we enter into action and then it produces a cause. It is the same with good actions – if we cultivate bodhicitta, we have to apply it in order to produce a good action.

Bodhicitta is also something we recite. “I want to realize myself for the benefit of all beings, I have this intention.” This is something concrete. In Mahayana, they speak of “the Gift”. The greatest gift we can give is that of the teaching. There is also the material gift. If someone does not have anything to eat, we can give them a little food or a little money, and they become very happy. We create a lot of virtue by doing this good action but we have to have the intention of giving this good gift. Sometimes we give with our own interests at heart, and that does not create a good action. If we have a good intention, we do not expect anything in return. Our only intention is for the benefit of someone who has some kind of need.

A practitioner should be very present every day of his or her life. In general, we have many evil intentions and this automatically produces a lot of negative power. In the teachings of Jigmed Lingpa he says, “If the intention is good, all of life and the fruit of life will be good, but if the intention is bad just the opposite happens.” So, try to cultivate good intentions. Good intention makes a lot of people happy and if people are very happy, you can produce a lot of very positive power in them.

I give many practices. In Tibetan Astrology there is something called a Black Year. In this Black Year all the elements and the influences are very bad. If a person is not careful, all these bad conditions and all the secondary causes will produce trouble for that person. During this time the weakness in the circumstances of the person, such as sickness, may manifest and if that person does not have much protection, they can be hit pretty badly. If they are very passive, they receive all this negativity. The aim of astrology is to understand the condition of the individual and their circumstances.

What can we do to remedy this? In astrology there are many methods to overcome these problems. If one does nothing the condition will get worse. To reinforce the energy of the individual, we can make prayer flags. We can do Long-life practices. There are many simple ways of overcoming negativities. There is a practice called Chi Thun. Chi means child and Thun to celebrate. We invite a lot of children, make some gifts and do a lot of things to keep them amused all day for many hours – these children will be full of joy – and the power of the joy of these children has a great potentiality to overcome all kinds of negativities.

You see how powerful the mind is when it is happy or the opposite. Also, giving gifts to poor people has the same motive. So, in life, one has to understand this. When many kinds of circumstances arise in our life like this, try not to make people unhappy, try to make them as happy as possible, and if we have the minimum of good intention and understanding, it is not very difficult to make people happy.

If we dissolve our tensions and become friendly to people, we are certainly happier for a few hours. Basically the fundamental thing to reach in practice is relaxation, so we can see how important relaxation is. Many teachings talk about bodhicitta as a kind of propaganda, to demonstrate something very sweet in society. Society does not function like that, with something false.

Many Dzogchen practitioners feel they do not need to practice bodhicitta, however one has to arrive at applying bodhicitta, even if one wishes to be a Dzogchen practitioner. I think our practitioners have to work hard on developing bodhicitta. With bodhicitta we have to understand our own essence, the condition of every individual.

People say many Dzogchen practitioners do not seem to have much love. If we are lacking love, it means we have become like a stone. It is not that we have to think about love, it is that we have to become a little more sensitive. Sensitivity means to be aware of time, of circumstances, and the human condition. It is very important to have respect for each other. Without respect, nothing works. Respect arises from observing and becoming sensitive to oneself. It is much better to become sensitive to oneself than to go out and try to make others sensitive.

Many people are used to criticizing others. We have a dualistic way of seeing that is characteristic of our general way of being. We have two eyes and as soon as we open them, they identify another object. We never observe ourselves, we are always looking outside, so we have developed our technology of criticizing others. We are always looking outside, looking for the guilty one.

If we are always looking outside, making other people feel guilty, our existence never changes and we never become sensitive. It is better to observe and analyze ourselves. If we are more aware and sensitive, other people, who may be very arrogant, will come around. A person will become harder if we try to educate them. If we do not have a feeling of guilt and remain calm, there is nothing to defend. We need to try and dissolve these tensions in ourselves.

This is a very important aspect between, for example, husband and wife, or people who are together and participate in the teachings. A spiritual relationship is hundreds of times more important than any normal relationship. If we ruin this and create problems between one practitioner and another, this is very negative and sad and becomes a heavy obstacle for realization.

Teaching given during the Easter retreat at Merigar, Italy, 1991. Republished from The Mirror issue 8, May 1991. https://melong.com/chogyal-namkhai-norbu-on-bodhicitta/?fbclid=IwAR2z_eP2_Yk4SLShWKFYrE9s2VefjjNxD2DzChaRgEYaW_lp7hnTJq1Klio