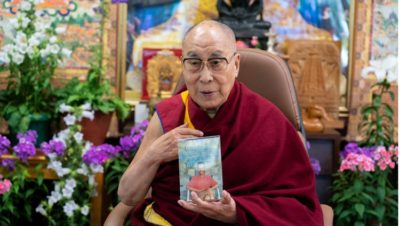

His Holiness the Dalai Lama holding a photograph of Francisco Varela that he keeps at home at the start of the ‘Dialogue for a Better World – Remembering Francisco Varela’ on June 9, 2021. Photo by Ven Tenzin Jamphel

June 9, 2021. Thekchen Chöling, Dharamsala, HP, India – When His Holiness the Dalai Lama entered the room in his residence from where he takes part in online virtual meetings this morning, he brought with him, and held up for all to see, the photograph of Francisco Varela that he keeps at home. Gábor Karsai, Managing Director, Mind & Life Europe welcomed him to a ‘Dialogue for a Better World – Remembering Francisco Varela’, the first event in a series called ‘Francisco & Friends: an Embodiment of Relationship’. The series commemorates Varela, one of the key founders of Mind & Life, who passed away just over twenty years ago. Karsai invited everyone to view a number of photographs from early Mind & Life meetings featuring Varela.

Dr Pier Luigi Luisi, Professor Emeritus of Biochemistry at ETH, Zurich, opened the conversation. He recalled being present at an event in Alpbach, Austria, in 1983, when His Holiness and Francisco Varela first met. It was an occasion that took place in an atmosphere of love and friendship. Luisi asked what made friendship with Varela special for His Holiness.

“Since I was very young,” His Holiness replied, “I’ve had an interest in mechanical things. I had a movie projector that had belonged to the 13th Dalai Lama and my curiosity about how the small battery produced the power to drive and illuminate the projector stimulated an interest in electricity. At the same time, from my childhood I was engaged in studying Buddhist philosophy.

“When I met Varela, I met someone who was a scientist, but who was also deeply interested in Buddhism. When he spoke from a Buddhist point of view he would say, “I’m saying this wearing my Buddhist hat” and later when he was offering a scientific opinion, “Now I’m wearing my scientist’s hat.” I realized that I needed someone like him who understood Buddhism but who was also professionally a scientist. He impressed me and I will always remember him. Even today I keep his picture in my room.

“Later, I was able to meet many more scientists. Science seems most recently to have developed in the West where Christianity, Judaism and to some extent Islam are followed. But there wasn’t much talk about the mind and emotions among scientists or religious people. And yet the mind is sophisticated. It enables us to think, to meditate and to change.

“To tackle our emotions, we need a better understanding of the way the system of mind and emotions works. Francisco Varela showed by example that science and Buddhism can work together side by side.

“He and I believe we live life after life and I’m quite sure that Varela will have found his next life among my close friends. Whether we recognise each other or not, we will have strong feelings for each other as a result of our experience in his former life. When I was very young some people who had been close to the 13th Dalai Lama came to my house and I recognized who they were.

“Varela and I developed a strong connection and I’m sure that if I live another 10-20 years, I’ll meet a child who has something special to say about him. Now I’m happy and proud to talk about my old friend and I’m glad to see his wife is with us too.

“This topic, ‘Dialogue for a Better World’ is important. In today’s world with its extensive material development, that includes the manufacture of weapons, there is too much emphasis on my nation, my people. Leaders have only a narrow focus. When another group of people adopt a different point of view, we too easily regard them as hostile and refer to them as our enemies. However, by and large scientists are more concerned with the whole of humanity rather than with this or that group.

“Today, there is too strong a sense of ‘us’ and ‘them’. There’s too much sense of ‘my friends’ or ‘my enemy’. But we can change that. I’m committed to the idea of the oneness of humanity. As human beings we are all the same. What’s more we all have to live together on this planet. We have a global economy. We depend on each other. Therefore, we must think of the welfare of all seven billion human beings now alive.

“The past was spoiled by too much violence. But look at what the European Union (EU) has achieved. Longstanding enemies France and Germany were able to overcome their historical hostility and build the EU. Since then, no fighting or killing has taken place among the member states. Why can’t the whole world adopt such a point of view? Instead of only thinking of my nation, think of the whole world in terms of us. This is something I’m committed to encouraging.

“However, I’m just a refugee living in India, a country with which we have long connections. India is our neighbour, but it is also the source of all our knowledge. It’s like our ancient home.

“Cultivating an appreciation of the oneness of humanity makes me feel comfortable because it helps me feel that wherever I go, whoever I meet is another human being like me. As human beings we are all brothers and sisters. Thinking of the oneness of all the human beings on this planet brings peace of mind because there is no place for fear or mistrust.

“I’m committed to sharing this idea of the oneness of humanity and a recognition of the value of all religious traditions, because all teach the importance of loving kindness. I’m also committed to ecology. Older generations in Tibet told me that there used to be more snow than there is now. This is crucial because Tibet is the source of the major rivers that supply water to large parts of Asia. Consequently, we have to protect the environment.”

Amy Cohen Varela, Chair, Mind & Life Europe, asked His Holiness why he has given so much time to engaging in dialogue with scientists. He answered in Tibetan, which was translated into Tibetan by Thupten Jinpa, that as a Buddhist he asks himself daily what he can do to help all sentient beings. He reflects on a key verse from Shantideva’s ‘Entering into the Way of Bodhisattva’:

As long as space endures,

And as long as sentient beings remain,

Until then, may I too remain

To help dispel the misery of the world. 10/55

He also ponders a stanza from Nagarjuna’s ‘Precious Garland’:

May I always be an object of enjoyment

For all sentient beings according to their wish

And without interference, as are the earth,

Water, fire, wind, herbs, and wild forests. 483

“Whatever help I can bring to this world,” he added, “I devote my life to that.

“In my own daily practice I emphasize cultivating the vast practice of the awakening mind, as well as the profound view of emptiness propounded by Nagarjuna. As far as the awakening mind is concerned, I put into effect a practice called equalizing and exchanging self and others. Shantideva had this to say by way of encouragement.

For one who fails to exchange his own happiness for the suffering of others, Buddhahood is certainly impossible-how could there even be happiness in cyclic existence? 8/131

All those who suffer in the world do so because of their desire for their own happiness. All those happy in the world are so because of their desire for the happiness of others. 8/129

“The problems we face are rooted in the idea we have of ‘I’ and ‘me’, ‘us’ and ‘them’. Let’s set aside the thought of all sentient beings and think of at least trying to help all human beings. On the basis of such an affinity we’ll be able to change the way we think and behave so that we avoid doing others harm.”

Elena Antonova, Senior Lecturer in Psychology, Brunel University, London, asked His Holiness what effect conversations with scientists had had on his own thinking. He repeated that he’d been interested in science since he was a child, but once he reached India, he’d been able to meet practising scientists and learned that their understanding of the mind and emotions was inadequate. Where Buddhism describes 51 mental factors and subgroups among them, the English language has only one word—emotion.

This, he said, is significant because some of our emotions create problems for us. We need to learn techniques to tackle them. We need to discover the antidotes and ways to cultivate them if we are to deal with our most troublesome emotions. We’ll make progress as our understanding grows. From this point of view the Buddhist approach is similar to that of science.

“Science provides us with knowledge of the human body and the physical world in which we live. But we all want to find peace and joy and that means we have to take care of our minds. Emotions present a problem, but again the solution lies in the mind. Although anger is very disturbing, we can’t just wish it away. We can only deal with it by coming to recognise what triggers it, what consequences it can bring and how loving-kindness is an antidote to it. We need to take a first-person approach and learn to understand our own minds. Varela recognized the need to combine scientific and spiritual approaches and I thought, ‘It’s true’.

“I’m not that interested in promoting spiritual teachings as such, but I do believe we can employ knowledge spiritual teachings contain in a secular context. Children can train their brains to remember information, but in the ancient Indian traditions there was an emphasis on training the mind. This included developing different kinds of intelligence, swift, penetrating and vast intelligence which enable a much more comprehensive understanding. This can involve a universal approach to education while having nothing to do with religion.

“We have natural skills and capacities that can be enhanced with training. One thing I am looking forward to when the restrictions associated with the pandemic are lifted is spending time in Delhi tapping into ancient Indian knowledge of the mind and learning to apply the mental training it describes.”

His Holiness told Luisi that modern science is still heavily orientated towards a materialistic vision of the world. Even human experience is viewed in terms of the brain rather than in relation to consciousness. If the brain is the sole focus of attention and the subjectivity of consciousness is not taken into account it won’t provide a full picture of human experience. It will leave out the unique characteristic of consciousness or mind which is the felt, subjective dimension.

He observed that we all want to feel joy, but it comes down to our state of mind and whether we’ve found peace within. His Holiness expressed a hope that science will be able to demonstrate and explain to schoolchildren as part of their education how to cultivate peace of mind, kindness and compassion, qualities that are so important for human life.

“Scientists are also human beings like the rest of us,” His Holiness noted. “They also face emotional problems and seek peace of mind. But learning to cultivate peace of mind requires a sound understanding of how the mind works. Following an analytical and contemplative approach can help to bring this about. Over the years, as our dialogues have gone on, more and more scientists have been paying attention to their own mental well-being.

“They’ve analysed how anger disturbs their peace of mind. They’ve examined what triggers it and how it arises. Shantideva uses a shift of perspective. He points out that from the point of view of someone cultivating patience, a hostile, irritating person becomes the best teacher. This kind of approach opens up a different way of seeing things such that real change can take place.

“Another aspect of this kind of enquiry related to emptiness involves being prepared to question who or what is this ‘I’ or ‘me’? What does it refer to? Anger and attachment are premised on basis that there is a real ‘me’ involved. There is a verse in Nagarjuna’s ‘Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way’ that examines the identity of the Tathagata or Buddha. We can reframe it in reference to ourselves and the relationship we have with our constituent parts.

“Reflecting on this verse we can recognise that ‘I’ am neither one with the mind-body constituents, nor different from them. The mind-body constituents are not (dependent) on ‘me’, nor am ‘I’ (dependent) on them. ‘I’ don’t possess the mind-body constituents. Who, then, am ‘I’? We find there is no real, solid self that we can point out.

“We need to take a two-pronged approach, examining the emotions and antidotes to them, but also questioning whether a real, solid ‘I’ or ‘me’ exists objectively as it appears. This will have some impact.

“Imagine,” His Holiness suggested, “that your strong emotions are personified as your opponents in debate. Challenge anger and attachment to say where is this ‘self’ they defend. Eventually they will concede there is no such self. We can really call into question many of the assumptions that lie behind our misconceptions. It’s not that we don’t exist, but we exist as a function of dependent arising. Objective reality is a false projection that has a powerful effect on our emotions.”

His Holiness alluded to verses in Chandrakirti’s ‘Entering into the Middle Way’ that refer to soaring to enlightenment and liberation on the two wings of conventional and ultimate truth.

With regard to promoting a sense of our common humanity, His Holiness observed that he sees this in practical terms. We share this one planet and our world really is interdependent. When there is too much division in terms of ‘us’ and ‘them’, it’s mutually destructive. Nobody wins. If, on the other hand, we strengthen our sense of the oneness of humanity and embrace those who are different from us, we can all learn to live more peacefully and more happily together. He said, this is a simple matter of survival.

His Holiness remarked that followers of theistic religious traditions have faith in a creator God, who they view as God the father. And as children of one God, they say we are all brothers and sisters. If we fight and kill each other, how will it make God the father feel? This, he declared, is a reason why we have to learn to live happily and harmoniously together.

Gábor Karsai noted that the meeting could not have ended on a better note. He thanked His Holiness for his wisdom and friendship, which, he said, has given rise to a whole new field of study — contemplative science.

https://www.dalailama.com/news/2021/dialogue-for-a-better-world-remembering-francisco-varela, https://www.dalailama.com/videos/dialogue-for-a-better-world-remembering-francisco-varela