Finora l’India è sopravvissuta alle previsioni pessimiste di una balcanizzazione, ma la Cina sembra voglia provarci ancora.

Un articolo su un sito “semi-ufficiale” cinese descrive le tappe per dividere l’India in 20 o più staterelli, sostenendo nazionalisti, separatisti, pakistani, tamil, srilankesi e bangladeshi. Preoccupazioni di New Delhi. Ma finora l’India, sebbene scossa da tante tensioni, ha sempre tenuto.

Il governo di New Delhi ha presentato una protesta ufficiale per i contenuti di un articolo pubblicato su un sito cinese, che mira a dividere l’India in “20-30 staterelli”, sostenendo guerriglie e nazionalisti presenti all’estero e all’interno della grande democrazia indiana.

Apparso l’8 aprile scorso sul sito internet www.iiss.cn (China International Institute for Strategic Studies) l’articolo descrive con minuzia una roadmap per dividere l’India: “Per frantumare l’India, la Cina può servirsi di paesi come il Pakistan, il Nepal ed il Bhutan; può dare una mano all’Ulfa [il gruppo separatista dell’Assam] nell’ottenere il suo obiettivo d’indipendenza in Assam; appoggiare le aspirazioni di gruppi nazionalisti come i Tamil ed i Naga; incoraggiare il Bangladesh a dare una spinta per l’indipendenza del Bengala occidentale e alla fine riprendersi i 90 mila kmq del Tibet meridionale”.

Il governo indiano è preoccupato di sapere se questa agenzia stampa è rappresentativa del pensiero del governo cinese. I media indiani parlano di “un website cinese quasi-ufficiale”.

Dicerie sulla balcanizzazione dell’India sono vecchie quanto lo Stato indiano. Subito dopo l’indipendenza, nel

Tawang, Monumento canotafio ai soldati indiani uccisi dai cinesi nella guerra del 1962

1947, nei circoli politici europei, molti osservatori predicevano che, dopo il tragico inizio di divisione col Pakistan, l’India non sarebbe rimasta unita.

Dopo tutto l’India non è mai stata una singola unità politica. L’impero britannico l’ha messa assieme ed ha fissato confini all’ovest, al nord ed all’est. Il Paese attuale non ha nemmeno una lingua comune. Subito dopo l’indipendenza ci sono state controversie per la delimitazione degli stati interni. Il criterio seguito per delimitare i confini è stato quello linguistico. Ma molti Stati stanno ancora litigando per i confini e per l’utilizzazione dell’acqua dei fiumi; Chennai ed il Tamil Nadu si preoccupano dei loro fratelli tamil in Sri Lanka e a Bangalore; i sette Stati del nord-est sentono di essere trattati come colonie militari di Delhi e al loro interno vi sono gruppi di guerriglieri; il Kashmir è in subbuglio da 25 anni per la secessione o per una più larga autonomia; in molti Stati centrali la guerriglia maoista-naxalita è attiva da decenni.

All’esterno, tutto questo può dare l’idea che la coesione dell’India sia molto debole e la sua frantumazione possibile.

Finora l’India è sopravissuta alle previsioni pessimiste di una balcanizzazione, ma la Cina sembra voglia provarci ancora. L’articolo del sito continua dicendo che “in vista di tutto questo, la Cina per il suo interesse e per il progresso di tutta l’Asia, dovrebbe allearsi ai movimenti nazionali come quello dell’Assam, quello tamil, quello del Kashmir ed appoggiare la formazione di nazioni-stato indipendenti fuori dall’India.” E tutto questo dovrebbe essere fatto per il progresso del subcontinente: “Solo quando l’India è stata divisa in un 20-30 staterelli sarà possibile avere una vera riforma ed un vero progresso sociale nel paese.”

Un articolo di questo genere convincerà i duri dell’India che la Cina abbia un piano per assediare l’India in alleanza coi regimi del Pakistan, Bangladesh e Nepal, e per appoggiare gruppi d’insurrezione.

Qualche giorno dopo la protesta di New Delhi, il fondatore ed editore del sito www.iiss.cn, Kang Lingyi, ha affermato che lui stesso ha editato il sito senza nessun intervento del governo e che l’articolo è stato scritto da un autore anonimo.

Uno degli ultimi check point indiani ai confini ccon la Cina nell'Arunachal Pradesh a Tawang

M D S Rajan, direttore del Chennai Centre for China Studies, che ha tradotto l’articolo dal cinese e l’ha pubblicato, afferma: “I cinesi parlano all’India in toni differenti. Questa tonalità è semiufficiale, ma non completamente. In tal modo, il governo cinese ha la possibilità di negare, ma vi sono stati una serie di pronunciamenti [ufficiali] di tono simile”. CT Nilesh http://www.asianews.it/index.php?l=it&art=16113&size=A#

07.08.2009

Riprendono i colloqui per i confini contesi tra Cina e India

I confini sono incerti dalla guerra del 1962. Pechino rivendica quasi l’intero Arunachal Pradesh, mentre l’India chiede indietro circa 43mila kmq di territorio. Intanto le parti rinforzano i propri militari presso le frontiere.

New Delhi (AsiaNews/Agenzie) – Riprendono oggi, dopo un anno di interruzione, i colloqui tra India e Cina per definire i confini tra i due Paesi, incerti dopo la guerra del 1962. Per due giorni a New Delhi si incontrano delegazioni di massimo livello, guidate dal Consigliere cinese di Stato Dai Bingguo e dal consigliere indiano per la Sicurezza M.K.Narayanan (nella foto). Gli esperti sono pessimisti sull’attuale possibilità di fare passi avanti.

I colloqui non sono facili, con New Delhi che accusa Pechino di avere creato forti strutture militari nelle regioni di confine Tibet e Xinjiang; a sua volta negli ultimi mesi l’India ha schierato nuove truppe e aerei presso il confine nell’Arunachal Pradesh.

L’India ha pure espresso preoccupazione per il progetto cinese di portare il treno espresso dal Qinghai-Tibet fino alle prefetture di Xigaze e Nyingchi, presso

Bandiere di preghiera tibetane, simbolo d'armonia e di pace, sventolano nella nebbia del mattino al Sela Pass nella regione di Tawang dell'Aunachal ai confini del Tibet

il confine.

La Cina rivendica circa 90mila chilometri quadrati di territorio, tra cui buona parte dell’Arunachal Pradesh che chiama Tibet meridionale. A sua volta l’India rivuole indietro circa 43.180 kmq nella regione Aksai Chin, al confine con il Kashmir, compresi 5.180 kmq ceduti dal Pakistan alla Cina. Quest’ultima richiesta accende l’ostilità cinese, che ricorda di avere ricevuto la zona nel 1963 dal Pakistan che la possedeva.

All’inizio del 13° colloquio di pace c’è stato qualche tentativo delle due parti di smussare le asperità. Molti media indiani raccomandano di non demonizzare il potente vicino. Il ministro indiano per gli Affari esteri S.M. Krishna ritiene difficili risultati immediati e afferma che occorrono tempo e pazienza. Zhang Yan, ambasciatore cinese in India, dice che i due Paesi sono “grandi vicini” e ricorda come i loro crescenti rapporti economici esigono di trattare i problemi esistenti con prudenza e disponibilità.

Queste parole contrastano con i violenti attacchi antiindiani operati dai media statali cinesi nei giorni scorsi. Al punto che Brahan Chellaney, professore di Studi strategici al Centro di ricerche politiche a New Delhi, ritiene che “l’obiettivo della Cina è impegnare l’India in colloqui senza esito, mentre intanto può cambiare a proprio favore il rapporto di forze sviluppando centri e strutture militari nella zona himalayana”.

China and India Dispute Enclave on Edge of Tibet

By EDWARD WONG

TAWANG, India — This is perhaps the most militarized Buddhist enclave in the world.

Perched above 10,000 feet in the icy reaches of the eastern Himalayas, the town of Tawang is not only home to one of Tibetan Buddhism’s most sacred monasteries, but is also the site of a huge Indian military buildup. Convoys of army trucks haul howitzers along rutted mountain roads. Soldiers drill in muddy fields. Military bases appear every half-mile in the countryside, with watchtowers rising behind concertina wire.

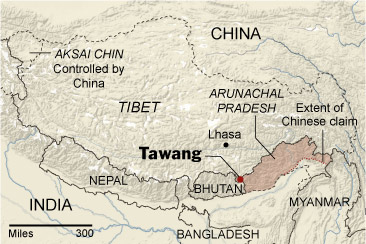

Tawang sulla mappa

A road sign on the northern edge of town helps explain the reason for all the fear and the fury: the border with China is just 23 miles away; Lhasa, the Tibetan capital, 316 miles; and Beijing, 2,676 miles.

“The Chinese Army has a big deployment at the border, at Bumla,” said Madan Singh, a junior commissioned officer who sat with a half-dozen soldiers one afternoon sipping tea beside a fog-cloaked road. “That’s why we’re here.”

Though little known to the outside world, Tawang is the biggest tinderbox in relations between the world’s two most populous nations. It is the focus of China’s most delicate land-border dispute, a conflict rooted in Chinese claims of sovereignty over all of historical Tibet.

In recent months, both countries have stepped up efforts to secure their rights over this rugged patch of land. China tried to block a $2.9 billion loan to India from the Asian Development Bank on the grounds that part of the loan was destined for water projects in Arunachal Pradesh, the state that includes Tawang. It was the first time China had sought to influence the territorial dispute through a multilateral institution. Then the governor of Arunachal Pradesh announced that the Indian military was deploying extra troops and fighter jets in the area.

The growing belligerence has soured relations between the two Asian giants and has prompted one Indian military leader to declare that China has replaced Pakistan as India’s biggest threat.

Economic progress might be expected to bring the countries closer. China and India did $52 billion worth of trade last year, a 34 percent increase over 2007.

Bondia, Arunachal India: Dolma avvolge nel suo fiammante mantello il suo piccolo Tenzin.

But businesspeople say border tensions have infused business deals with official interference, damping the willingness of Chinese and Indian companies to invest in each other’s countries.

“Officials start taking more time, scrutinizing things more carefully, and all that means more delays and ultimately more denials, “ said Ravi Bhoothalingam, a former president of the Oberoi Group, the luxury hotel chain, and a member of the Institute of Chinese Studies in New Delhi. “That’s not good for business.”

The roots of the conflict go back to China’s territorial claims to Tibet, an enduring source of friction between China and many foreign nations. China insists that this section of northeast India has historically been part of Tibet, and should be part of China.

Tawang is a thickly forested area of white stupas and steep, terraced hillsides that is home to the Monpa people, who practice Tibetan Buddhism, speak a language similar to Tibetan and once paid tribute to rulers in Lhasa. The Sixth Dalai Lama was born here in the 17th century. The Chinese Army occupied Tawang briefly in 1962, during a war with India fought over this and other territories along the 2,521-mile border.

More than 3,100 Indian soldiers and 700 Chinese soldiers were killed and thousands wounded in the border war. Memorials here highlighting Chinese aggression in Tawang are big draws for Indian tourists.

“The entire border is disputed,” said Ma Jiali, an India scholar at the China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations, a government-supported research group in Beijing. “This problem hasn’t been solved, and it’s a huge barrier to China-India relations.”

In some ways, Tawang has become a proxy battleground, too, between China and the Dalai Lama, the exiled spiritual leader of the Tibetans, who passed through this valley when he fled into exile in 1959. From his home in the distant Indian hill town of Dharamsala, he wields enormous influence over Tawang. He appoints the abbot of the powerful monastery and gives financial support to institutions throughout the area. Last year, the Dalai Lama announced for the first time that Tawang is a part of India, bolstering the India’s territorial claims and infuriating China.

Tawang Arunachal India: Pema e Dolma guardano lontano verso l'incerta frontiera con la Cina, un tempo era la via verso il territorio del Tibet.

Traditional Tibetan culture runs strong in Tawang. One morning in June, the monastery held a religious festival that drew hundreds from the nearby villages. As red-robed monks chanted sutras, blew horns and swung incense braziers in the monastery courtyard, the villagers jostled each other to be blessed by the senior lamas.

At the monastery, an important center of Tibetan learning, monks express rage over Chinese rule in Tibet, which the Chinese Army seized in 1951.

“I hate the Chinese government,” said Gombu Tsering, 70, a senior monk who watches over the monastery’s museum. “Tibet wasn’t even a part of China. Lhasa wasn’t a part of China.”

Few expect China to try to annex Tawang by force, but military skirmishes are a real danger, analysts say. The Indian military recorded 270 border violations and nearly 2,300 instances of “aggressive border patrolling” by Chinese soldiers last year, said Brahma Chellaney, a professor of strategic studies at the Center for Policy Research, a research organization in New Delhi. Mr. Chellaney has advised the Indian government’s National Security Council.

“The India-China frontier has become more ‘hot’ than the India-Pakistan border,” he said in an e-mail message.

Two years ago, Chinese soldiers demolished a Buddhist statue that Indians had erected at Bumla, the main border pass above Tawang, a member of the Indian Parliament, Nabam Rebia, said in a session of Parliament.

Tawang became part of modern India when Tibetan leaders signed a treaty with British officials in 1914 that established a border called the McMahon Line between Tibet and British-run India. Tawang fell south of the line. The treaty, the Simla Convention, is not recognized by China.

“We recognize it because we agreed to it,” said Samdhong Rinpoche, prime minister of the Tibetan government-in-exile. “If China agreed to it now, it would be a recognition of the power of the Tibet government at that time.”

China has grown increasingly hostile to the Dalai Lama after severe ethnic unrest in Tibet in 2008. This year, it turned its diplomatic guns on India over the Tawang issue. China moved in March to block a $2.9 billion loan to India from the Asian Development Bank, a multination group based in Manila that has China on its board, because $60 million of the loan had been earmarked for flood-control projects in Arunachal Pradesh. The loan was approved in mid-June over China’s heated objections.

“China expresses strong dissatisfaction to the move, which can neither change the existence of immense territorial disputes between China and India, nor

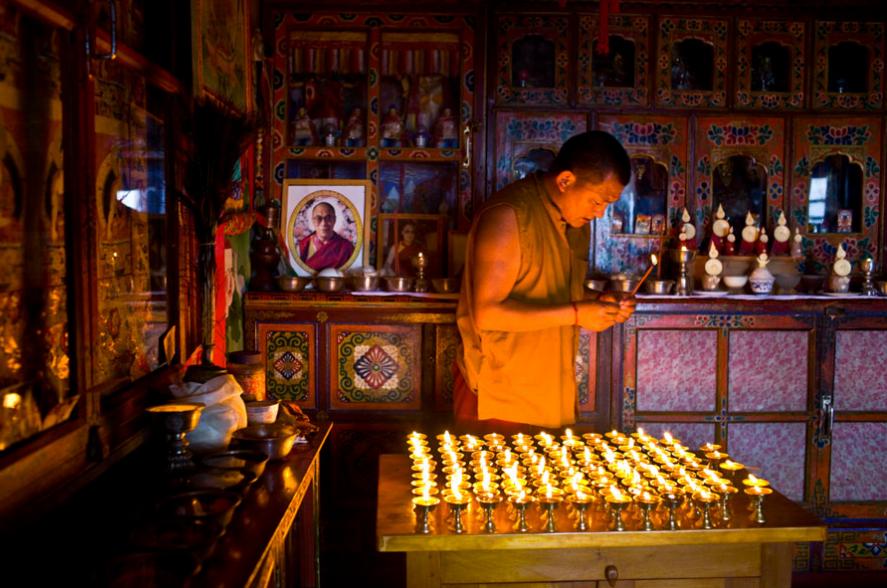

Al monastero di Tawang ilmonaco Tenzing fa l'offerta delle luci

China’s fundamental position on its border issues with India,” Qin Gang, the Foreign Ministry spokesman, said in a written statement.

In May, weeks after China first tried to block the loan, the chief of the Indian Air Force, Air Chief Marshal Fali Homi, now retired, told a prominent Indian newspaper that China posed a greater threat than Pakistan.

Another official, J. J. Singh, the governor of Arunachal Pradesh and a retired chief of the Indian Army, said the next month that the Indian military was adding two divisions of troops, totaling 50,000 to 60,000 soldiers, to the border region over the next several years. Four Sukhoi fighter jets were immediately deployed to a nearby air base.

Since 2005, when Prime Minister Wen Jiabao of China visited India, the two countries have gone through 13 rounds of bilateral negotiations over the issue. A round was held just last month, with no results.

“The China-India border has got to be one of the most continuously negotiated borders in modern history,” said M. Taylor Fravel, an associate professor of political science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who is a leading expert on China’s borders. “That shows how intractable this dispute is.”

Xiyun Yang contributed research from Beijing.

August 26, 2009 http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/26/world/asia/26dalailama.html?ref=asia

Waiting for Reincarnation at a Spiritual Birthplace

By EDWARD WONG

URGELLING, India — He drank wine, cavorted with women and wrote poetry that spoke of life’s earthly pleasures.

He was the Sixth Dalai Lama, the spiritual leader of the Tibetans and reincarnation of Chenrezig, a deity embodying compassion.

He would sneak out of the Potala Palace in the heart of Lhasa, the Tibetan capital, for midnight trysts. He renounced his monastic vows in the middle of his

Soldati indiani in pellegrinaggio nel monastero buddista di Tawang

stewardship of Tibet. He was later kidnapped by Mongolian warriors allied to the Manchu Chinese court and died in captivity about three centuries ago at the age of 33 — or so one story goes. Another tells of his winning his freedom and wandering the Tibetan lands as an ascetic.

So goes the legend of Tsangyang Gyamtso, one of the most popular historical figures among Tibetans and the most colorful of the long line of Dalai Lamas. His poetry is among the most iconic in Tibetan literature.

In this remote area of the eastern Himalayas, the mystique surrounding the Sixth Dalai Lama is magnified a hundredfold. He was born here in Urgelling, called Ugyenling in Tibetan, a village in the lush hills that border Bhutan and the Tibet Autonomous Region of China. The dominant ethnic group here is the Monpa, a Buddhist people who speak a language closely related to Tibetan but consider themselves distinct from the Tibetans on the high plateau.

The two-story childhood home of the Sixth Dalai Lama was turned into a pilgrimage shrine centuries ago. Candles flicker in front of the main altar, and prayer flags adorn a large tree outside.

“He’s pure Monpa, the only Monpa to be a Dalai Lama,” said Jamparema, 60, a hunched woman in a striped red dress who was pouring oil out of brass candle holders in the altar room. Since her youth, she said, she had taken care of the shrine.

The fact that the Sixth Dalai Lama came from this area, called Tawang, is one of the reasons that China gives in asserting that Tawang is a part of Tibet, and

Soldati indiani in pattugliamento dei bollenti confini con la Cina a Tawang

thus part of China. Indian officials say the land was ceded to British-ruled India by Tibetan leaders in the Simla Convention of 1914.

Given the precedent of the Sixth Dalai Lama, some people here mention Tawang as a possible birthplace for the next Dalai Lama. The current one, the 14th — who fled to exile in India in 1959, passing by this village on his route — has said his reincarnation could very well be born outside of Chinese-ruled Tibet.

The shrine here has traditional thangka paintings of most of the 14 Dalai Lamas. Nine white stupas in a room on the ground floor supposedly house remains of the Sixth Dalai Lama’s relatives.

As for signs of the Sixth Dalai Lama himself, there is a small wooden box with a stone inside that has a faint footprint — supposedly his, even though he was taken from this area before he turned 3. He never returned.

A small museum in the sprawling Tawang Monastery, which sits above here at 10,000 feet, displays necklaces of turquoise and other precious stones said to have belonged to the Sixth Dalai Lama’s mother.

Long ago, the leader of Tawang Monastery came here to collect the family’s possessions. He was afraid they would be spirited away by Tibetan officials in

Monaci novizi alla preghiera del mattino nel monastero di Tawang

Lhasa, said Gombu Tsering, 70, the museum’s caretaker.

“The Tibetan government would have sent a spy from Lhasa to collect all this,” he said. “That’s why we collected it. A shoe of the mother was taken by a spy.”

The Sixth Dalai Lama had a complicated relationship with Lhasa, according to the definitive biography of him, “Secret Treasures and Hidden Lives,” by Michael Aris, a Tibet scholar at Oxford University. Mr. Aris, who died in 1999, was the husband of Daw Aung Sang Suu Kyi, the opposition leader in Myanmar.

“It is difficult to think of a more enigmatic or elusive figure in Tibetan and Himalayan history,” Mr. Aris wrote.

The Sixth Dalai Lama’s path to the throne in Lhasa was far from linear. His predecessor was the first leader to unify all of Tibet into a vast state since the collapse of the early Tibetan empire in the ninth century. The Fifth Dalai Lama died in 1682, and his reincarnation was identified here the next year.

But for various reasons, the Fifth Dalai Lama’s death was kept a secret for 15 years by Sangye Gyamtso, the chief regent. A monk who resembled the Dalai Lama even lived in the lama’s apartments and impersonated him when Mongolian leaders came to visit, wearing an eyeshade of horsehair to mask his appearance, Mr. Aris wrote.

The Sixth Dalai Lama, once he was identified by a search committee, was taken with his family across the Himalayas to a remote town called Tsona, where

Bandiere di preghiera sventolano sulla casa che vide l'infanzia del VI Dalai lama

they lived under a form of house arrest for the next 12 years. That was to help maintain the veil of secrecy surrounding the death of his predecessor. The boy studied Buddhist texts in strict isolation; even visits from his own relatives within the compound were carefully controlled.

When he was finally enthroned in 1697, at age 14, he was thrust into the greatest spotlight in all of Tibet, something for which his reclusive childhood had left him ill prepared.

He rejected all the trappings of his title. That meant renouncing his vows, wearing jewelry and growing his hair out.

Gray Tuttle, a professor of modern Tibetan studies at Columbia University, said in an interview that the Sixth Dalai Lama, if he had focused on ruling the land, could have consolidated the gains made by his predecessor and transformed Tibet into a strong state with the ability to resist Chinese encroachment.

“This is where the Sixth Dalai Lama really could have played an important role, but because of his lack of training, lack of being raised as a Dalai Lama, he went off and did these other activities,” Mr. Tuttle said. “But the Tibetans loved him for that, loved

Pasang da anni offre le sue lampade di burro al cenotafio del VI Dalai Lama

his writings.”

Even today, and even in the West, his poetry resonates. Last year, The Harvard Advocate, a literary magazine, published a selection of his work, as translated by Nathan Hill and Toby Fee. The first poem is perhaps his best known:

From top the eastward peak;

arose the clear white moon:

her immaculate face

turned and turned in my mind

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/26/world/asia/26dalailama.html

September 4, 2009